Last January the Belgian curator Frie Leysen was invited to give the closing keynoteaddress/speech of the Australian Theater Forum. She did not mince her words: ‘We have built theatres and arts centers, and we created festivals to produceand present art works and to welcome audiences in the best possible conditions.

But, during the years, most of these structures and organizations have become

rusted and sclerosized. They have become dinosaurs. (…) Originally meant to

support the artists, they got organized very well, often too well, and so lost

the needed flexibility to respond to the specific needs of specific works. The

artists now have to follow the policy and the rules of the houses instead of

the other way around.’ (The full lecture can be accessed here).

If we take a look at our Dutch playhouses, it is not too

difficult to see what Leysen is getting at: all plays seem to be made to fit

either the big or the small frontal stage; new, let alone experimental, theatre

is hard to find whereas there are plenty of adaptations, mostly of canonical

plays, which fit the classical structure of the play house like a glove.

Leysen knows the Dutch

situation all too well, as she made clear in her acceptance speech for the Dutch

Erasmus Price awarded to her last year. She rebelliously addressed King

Alexander sitting in front of her: ‘Your Majesty, your country has become a

place where the arts can barely breath.’ ‘How is it possible’, she continues, ‘that

one of the richest countries of the world no longer allows artists to

experiment and to think outside of the box?’ She is obviously referring to the

budget cuts of the previous government, effectively discouraging the creation

of new and temporary companies, and to the decision to stop supporting

‘artistic workshops, labs and research centers’. But the cuts go deeper, even

to the production level of the surviving companies. Whereas in the past few

decades theatre makers have had the tendency to look beyond the traditional playhouse

for new and different performance spaces (e.g. Dogtroep or Lotte van den Berg),

the current organization of city theatres no longer seems to embrace this

opportunity and for festivals it ironically almost seems a must to do so, rather

out of lack of performance space than because of it. They stick to the

habitual, fearing the risk more than the dinosaur.

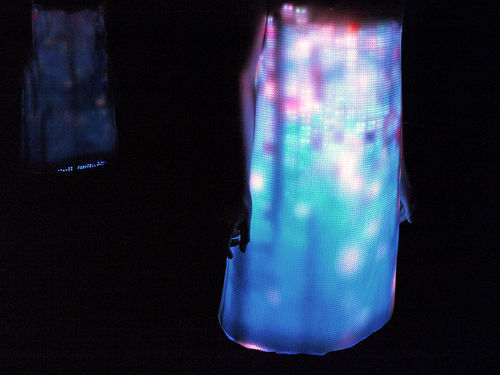

A few months ago, the Arnhem-based theatre company Toneelgroep Oostpool performed ‘The Immortals’ in art house Lux in Nijmegen. At first sight this company seems to have adapted to the dinosaur type: in the past years they have been able to draw large audiences to their well-made adaptations of Shakespeare and modern novels like Virginia Woolf’s Orlando for either the small art house stage or the big playhouse stage. However, since the arrival of the new artistic team led by Marcus Azzini in 2012, its profile has been slightly adjusted. Oostpool still produces crafty adaptations of old and new classics, like ‘Reigen’ (Arthur Schnitzler) and ‘Angels in America’ (Tony Kushner), but it does so in combination with experimental plays mostly made by Suzan Boogaerdt and Bianca van der Schoot. The duo has established its own series called ‘Visual Statements’ which questions the contemporary obsession with visual culture, the spectacular and the self. Their performances, especially Hideous (Wo)men (2013) and The Immortals (2014), have troubled both the press and the usual Oostpool audience with their lack of plot and speech, as well as their ritualist hang-ups, involving many repetitive, gender-focused and abject scenes that disturb our view on television soaps (Hideous (Wo)men) and Youtube (The Immortals).

Interestingly, they also

have made an attempt to adapt and restructure the classical theater stage of

the playhouse to fit the concept of their performances. In Hideous (Wo)men, for instance, the audience has to watch a rotating

platform on which a television set is shown. The main structure remains

frontal, as the audience sits in the auditorium and the actors perform on

stage. Yet, in The Immortals the

auditorium is no longer used and the audience has to sit on stage trying to

peek into one of four rooms or to watch the flat screens showing what is

happening in the rooms: people broadcasting themselves endlessly. Once the

audience sits in its on-stage auditorium, the classical auditorium is no longer

visible and the classical stage loses its function as a stage. It turns into a

space very similar to what art houses and contemporary museums already have: a

performance room in which the dividing line between the audience and the performers

is less rigid. In other words, the production was performed in a space that was

not made for it. It is an inventive way of bringing their ‘visual statement’ to

the theatrical stage, no matter what that stage looks like, but it is also a

telling example of what Frie Leysen denounced in her keynote to the Australian

Theater Forum: the existing structures no longer adapt to the artists, the

artists have to adapt to the structures. They are obliged to dig around in the intestines

of the dinosaur. One never knows what can be found there, if one looks more

closely, but one does wonder what would be possible if the Dutch playhouses were

more keen on rethinking their structures and on inviting artists to do so as

well.

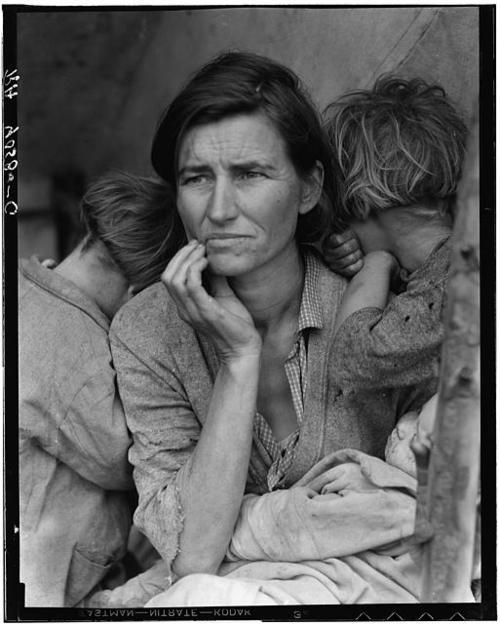

Image credits: The Immortals, Toneelgroep Oostpool, via http://www.toneelgroepoostpool.nl/nieuws/item/the-immortals-2