By Adil Boughlala and Anouk Stevens

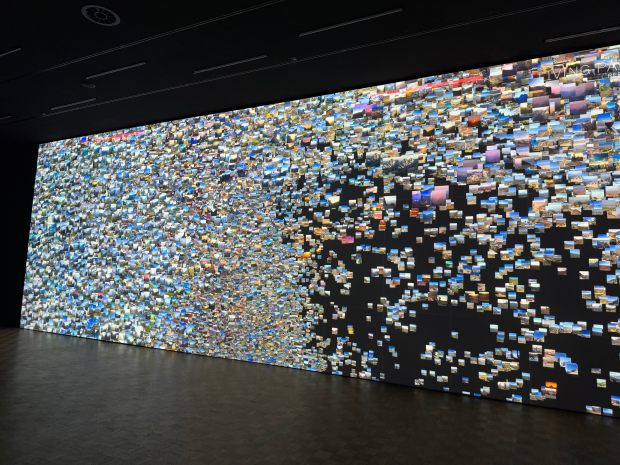

Wavelike patterns move gracefully across the screen as natural colours seamlessly ebb and flow, occasionally revealing snippets of images that resemble familiar landscapes of nature. Living Paintings: Nature at Kunsthal Rotterdam features Refik Anadol’s first solo exhibition in the Netherlands. The abstract artworks by Anadol provide visitors with a visual spectacle that explores the meaning of being human in an increasingly digitised society.1 Through the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Anadol creates AI Data paintings, or ‘living paintings’, that immerse the visitor in unthinkable yet recognisable landscapes. Whereas the introduction of new technologies seems to repeatedly highlight the divide between nature and culture – two strands that usually do not meet – the exhibition presents a symbiotic relationship between nature and technology. It blurs the boundaries between the ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’, and thus challenges traditional notions of what is ‘natural’ and ‘cultural’.

The ‘living paintings’ we saw reminded us of ecologies: they pose an immersive and interconnected environment of complex actors that seem to be always moving, always evolving, always ‘becoming.’2 Understanding Anadol’s works as algorithmic ecologies implies that algorithms are not isolated entities but exist within a system where they interact with each other, with data inputs, and with the environment in which they operate. Algorithms are not static, they evolve and adapt based on various factors, creating a dynamic and interconnected system akin to the interactions within an ecological environment. This ecological thinking allows for reflection on environmental conditions, and more broadly the interconnectedness of the planet and its inhabitants. We revisit the Living Paintings: Nature exhibition through this lens of ecologies.

The artist: Refik Anadol

The globally renowned Turkish-American new media artist Refik Anadol is known for his data-driven artworks. He adopts machine learning algorithms to create abstract, constantly changing, dream-like digital realms that usually address humankind’s impact on or position in natural environments. The exhibition displays Anadol’s most significant nature-themed artworks as triptychs, literal windows into a digital realm. Each series is composed of a dataset and features its own unique transformation of data into the artworks presented, from wind prediction data to images of natural parks. According to Anadol, these datasets serve as collective memories, memories that belong to everyone and should not be confined to personal or private memories.3

Contrary to common belief, the process of creating these AI data paintings requires a combination of algorithmic processing and human handpicking. Anadol does this together with a team of data scientists, researchers and designers who, together, form Refik Anadol Studio. By use of algorithms, Anadol ponders the question of whether machines can actually dream, hallucinate, or process individual and collective memories, a recurring element in the entirety of his oeuvre.4 Anadol’s body of work has introduced a new aesthetic to the artworld that intersects art, technology, nature and the human, and is distinctly recognisable as his.

Winds of LA & Artificial Realities: Pacific Ocean

Data allows us to anticipate natural phenomena. Should you wear a raincoat today? Are there potential risks and is it perhaps better to stay inside? The process of datafication allows us to gain knowledge on our natural environment yet it also abstracts our relationship to it by reducing nature into numerical data. The series “Winds of LA” and “Pacific Ocean” reverse this process and visualise data in a manner that becomes readable for non-experts. Both series integrate data collected from weather service companies: “Winds of LA” uses data collected from real-time API weather sensors placed around LA 5 and “Pacific Ocean” integrates publicly available datasets that are shared daily.6 Rather than rejecting the integration of data into our everyday lives, Anadol shows how, with the use of new technologies, artistic translations of data strengthen our understanding of and relationship to our environment. Although the datasets of these two works differ, both take as a point of departure the translation of data into poetic and fluid patterns. Whereas “Winds of LA” transforms data into blue and white squares that mimic the abrupt movements of the winds of LA, “Pacific Ocean” visualises data more smoothly, resulting in a fluid surface similar to the ocean. Instead of presenting data as tabular information, it is transformed into an affective and dynamic image. The natural flow of coloured data on-screen allows visitors to submerge themselves in the artworks and connect with the portrayed natural phenomena.

California Landscapes: Generative Study & Artificial Realities

“California Landscapes: Generative Study” and “Artificial Realities: California Landscapes” are two series based on the same dataset of over 153 million images of California’s National Parks. Despite sharing the same dataset, the two series feature two different visual representations: “Generative Study” creates images that are recognisable and similar to the national parks. Yet, the images continuously shift into new forms, visualising natural elements including skies, mountains, trees, waterfalls and much more in fluid ways. While doing so, it projects interconnected lines on top of the images, underlining the algorithmic work at play beneath the screens’ interface. You can see the machine working. Contrarily, “Artificial Realities” proposes a more abstract view of California’s National Parks, similar to “Winds of LA” and “Artificial Realities: Pacific Ocean”. The series draws on the natural pigments of nature, bringing together technology and nature visually, triggering a sense of belonging to the Earth.7 While ”Generative Study” presents more static and photorealistic images in which natural landscapes can be more easily recognised, ”Artificial Realities” offers a more fluid and immersive experience that explores the dynamic and ever-changing essence of nature. In other words, what distinguishes both series is the degree of abstraction utilised in their presentation. The juxtaposition of these approaches prompts reflection on the relationship between technology and nature; as nature is mediated through a flurry of computations, technology can provide us with different versions of how we can perceive nature.

The contrast between both series is also a testament to the nature of human-machine collaboration: “With the same data, we [Refik Anadol Studio] can generate infinite versions of the same sculpture, but choosing this moment, and creating this moment in time and space, is the moment of creation”.8 This approach not only attests to the need of human intervention, but it also acknowledges the reciprocal agency of algorithms in the creative act. The human is decentred as the algorithm assumes a prominent position. While Anadol decides the perimeters, it is the algorithm that decides the final result. The audience is then invited to reflect on the potential role of machine learning within art, but also to what extent the machine is part of the creative process.9

Living Painting: Immersive Room

Completely unique to this exhibition is Living Painting: Immersive Room. As you step inside this square-shaped box you are embraced by a three-dimensional, kinetic, multisensory space of spectacle that no image or video can do justice. The screens display the same patterns from Anadol’s AI data paintings while the mirrors, strategically placed on the floor and ceiling, create an infinite space in which your body becomes your only reference point. Within this space, you cease to be a mere observer; instead, you seamlessly integrate into the very fabric of Anadol’s artwork. You become an active participant in the algorithmic ecology, a living element within the computational tapestry. The boundaries between the observer and the observed dissolve, offering a rare opportunity to not just witness but also to embody the artist’s vision.

Being included in the algorithmic ecology extends beyond the conventional engagement of art. It also prompts reflection on environmental issues and an affective re-evaluation of our relationship with art, technology, nature, and the interconnectedness between them. Digital technologies are capable of evoking emotional resonance through storytelling; stories have the power to evoke empathy and affective connections with the natural world, which in turn can influence our attitudes and behaviours towards environmental conservation.10 Anadol’s works provide abstract narratives that resonate with us on an emotional and subconscious level, stirring deep-seated feelings of connection to the natural within.

Concluding remarks

Anadol’s works not only showcase algorithmic ecologies that intersect the realms of art, technology, nature and the human, but they also lend themselves exceptionally well to a relaxed and enchanting experience at the museum. Each video, well over 16 minutes long and presented in a dimly lit room, invites visitors to linger and lose themselves in a mesmerising, digital world of tranquillity. As you ponder your own thoughts, you might occasionally recognise a mountain or a sunset, which brings you back to the world around you.

Living Paintings: Nature is on show at Kunsthal Rotterdam until 1 April. Still not convinced? The exhibition is enjoyable for all ages:

Footnotes

- https://www.kunsthal.nl/en/plan-your-visit/exhibitions/refik-anadol/ ↩︎

- Iris van der Tuin and Nanna Verhoeff, Critical Concepts for the Creative Humanities (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2022). ↩︎

- Alina Cohen, ‘Refik Anadol’s Mesmerizing Data Paintings Are Captivating Audiences Worldwide’, Artsy, 15 February 2023, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-refik-anadols-mesmerizing-data-paintings-captivating-audiences-worldwide. ↩︎

- Refik Anadol and Pelin Kivrak, ‘Machines That Dream: How AI-Human Collaborations in Art Deepen Audience Engagement’, Management and Business Review 3, no. 1 & 2 (2023): 101–7. ↩︎

- https://refikanadol.com/works/winds-of-la/ ↩︎

- https://refikanadol.com/works/artificial-realities-pacific-ocean/ ↩︎

- https://refikanadol.com/works/artificial-realities-california-landscapes/ ↩︎

- Refik Anadol et al., ‘Modern Dream: How Refik Anadol Is Using Machine Learning and NFTs to Interpret MoMA’s Collection’, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), 15 November 2021, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/658. ↩︎

- Joanna Zylinska, ‘Art in the Age of Artificial Intelligence’, Science 381, no. 6654 (13 July 2023): 139–40, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh0575. ↩︎

- Alexa Weik von Mossner, Affective Ecologies: Empathy, Emotion, and Environmental Narrative, Cognitive Approaches to Culture (Columbus: The Ohio State UP, 2017). ↩︎