images of the financial crisis – 1866 and 2008

By Thomas Smits

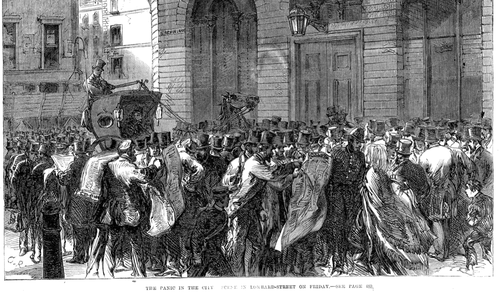

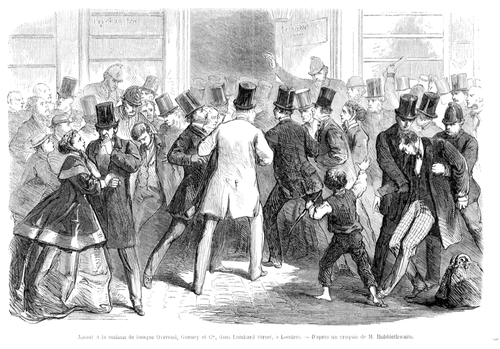

On May 19th 1866 curious images appear on the covers of the Illustrated London News and the French L’Illustration, the most famous illustrated newspapers of the nineteenth century. On the cover of the Illustrated News we see a crowd of top-hat-wearing men looking anxiously in large format newspapers, presumably the Times. The capitation reads: ‘The panic in the city. Scene in Lombard street on Friday’. The caption of the front page of L’Illustration is set to a different tune: ‘Siege of the office of the bank Overend, Gurney and Cie, Lombard street, in London’. Here we see a real panic: a crowd storming a bank, police trying to control the situation and a fainting man on the foreground. The cause of the ‘panic in Lombard Street’ is maybe already clear. Investors rushed to Lombard Street to get their money from the defaulting banking house of Overend, Gurney and Company.

It is not hard to compare the crisis of 1866 to the one that we are experiencing today. Overend and Gurney is often described as ‘the bankers bank’. The company dealt in bills of exchange: documents that guaranteed the payment of a specific amount at a specific date. Therefore, the bank can be compared to the financial institutions that caused the collapse of 2008. They were not involved in traditional products, like loans, but in the trade of financial derivatives. Overend and Gurney rose to prominence during the ‘Panic of 1825’, the first economic crisis that is not attributable to an external event, like a war, but mainly to speculative investment in Latin America including the imaginary country of Poyais (read more about it here and here). In 1825 the bank was able to extend loans to other banks that were bound to collapse and hereby started the so-called ‘interbank lending market’, an important component of our current financial system.

Were did it all go wrong? In the late 1850s the bank invested heavily in railway companies and other long-term loans. Ten years later the owners found that their short-term cash reserve amounted to only one million pounds while their liabilities were estimated at roughly four million (note that financial institutions in our time have far lower cash reserves). The directors of the bank reacted to this problem by turning their business into a limited company. In other words: they gave out stocks.

The newly acquired capital was invested in a rather irresponsible manner, as the early Marxist Henry Hyndman describes it, the directors of the bank “(…) were encouraging and embarking in enterprises of a character which were so unsound in themselves, and so dangerous from the class of people connected with them, that the veriest tyro [an absolute beginner] in finance would have instinctively shrunk from them (…)." Although the directors of Overend and Gurney were put on trial for fraud connected to these high-risk investments, the judge only found them guilty of ‘great error’ rather than criminal behaviour. This, of course, reminds us of the risks that employees in the financial sector are encouraged to take in our time (read the blog of Joris Luyendijk) and the lack of (legal) responsibility ascribed to them after the collapse of 2008.

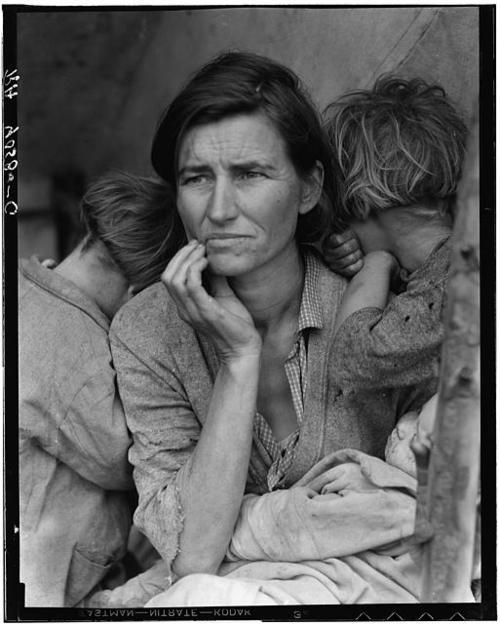

Because of major losses on the risky investments, the bank had to suspend payment on the 10th of May 1866. Shareholders rushed to the office of Overend and Gurney in Lombard Street to get their money and this lead to the chaotic scenes on the covers of the illustrated newspapers. Lets return to these images. How can we compare the visual coverage of the crisis of 1866 in the two illustrated newspapers to our ‘own crisis’? What and who do we see if we think about the current situation? Which images come to mind? What groups are seen as the victims of financial collapse? Type in ‘Great depression 1930’ on Google Images and you will find Dorothea Lange’s iconic Migrant Mother or a man holding up a sign ‘Work is what I want, not charity’. Personally, when I think of our crisis I see a young man, wearing an expensive suit, sitting behind his desk. He is staring at four, or maybe five, computer screens which all show the same descending red line. In other words: I see a poor investor, just like the ones on the covers of the illustrated newspapers in 1866. How is it that I don’t see an image of a family leaving their foreclosed home? A modern equivalent of Lange’s Migrant Mother? Why is it so hard for us – or at least for me – to imagine these victims of the crisis?

Image credits:

1: "RVS Handelsraum” by Raiffeisenverband Salzburg

2: Detail of: ‘The panic in the city: scene in Lombard street on Friday’, Illustrated London News (19 May 1866).

3: ‘Assaut a la maison de banque Overend, Gurney et Cie, dans Lombard Street, à Londres’, L’Illustration (19 May 1866).

4: D. Lange, ‘Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California [Migrant Mother] (1936). Via Library of Congress.

See the original pages of the illustrated newspapers here and here.

Images shared under creative commons.