Welcome

to the wonderful world of wearable surveillance! Thanks to the wearable GPS

tracker you will “never lose your pet

again”, and be able to track the location of your dementing relative or wandering child at any time.

No longer having to worry about the safety of our beloved pet, relative or

offspring us caregivers will finally have peace of mind, or so the

techno-utopian marketing story goes. But before you run off to the (web)store

to purchase this technological solution to all your ‘parental nerve’ you might

want to think again. And read this blog post, of course.

According to Belgian philosopher Kathleen

Gabriels, the “constant, remote, and often covert tracking of the other’s

data engenders a situation of what can be characterized as ‘quantified

otherness’”. In the specific case of

GPS trackers, this means that the geographic location of a physically distant

other can constantly, remotely, and unobtrusively be traced. Obviously, there

is little against the heartfelt wish

to care for, protect, and safeguard our beloved ones. The question, however, is

whether wearable GPS trackers are a desirable

and effective way to canalize and act upon this philanthropic inclination. Do

these wearables truly help prevent our vulnerable children, pets, and relatives

from getting lost or hurt, or is this the latest example of a surveillance

society gone mad?

A

few weeks ago, Dutch newspaper De

Volkskrant published an article entitled ‘Big Mother’, which connects the

parental urge to continuously supervise children to what sociologist Frank

Furedi terms ‘paranoid parenting’. “Today’s parenting style sees safety and

caution as intrinsic virtues”, Furedi

writes, “[p]aranoid parenting

involves more than exaggerating the dangers facing children. It is driven by

the constant expectation that something really bad is likely to happen to your

youngster”. There is no substantial empirical data suggesting that children wearing

a GPS tracker are indeed safer. After all, the technology will not prevent them

from falling or drowning, from being bullied or hit by a car. Kids trackers, in

other words, do not owe their appeal to their verifiable improvement of child

safety but to their capitalization of paranoid parenting fueled by a generally risk-averse

society. Depending on how they are

used, however, such wearables may nonetheless have a positive effect on the

parent-child relationship. Just the thought of being able to track a kid’s

location might turn the overprotective parent into a relaxed parent who is willing

to grant the child more autonomy and space for self-development.

Pet trackers relate to a similar phenomenon. On

the one hand, it seems like a win-win situation if these devices effectively

relieve the owner of the constant fear that something might happen to their

domestic companions and, hence, give the pet more freedom of movement. Considering

the omnipresence of heartbreaking “missing pet” posters in the contemporary

urban landscape, there is no doubt about the potential market for these

devices. On the other hand, however, pet owners (and parents/caregivers alike)

should be aware that GPS trackers decrease worries, rather than prevent any

identified danger or probable risk. The GPS technology will tell you where roughly

to look for your pet/child/relative, yet it is not fine-grained enough to identify

the exact location. Civilian GPS

trackers can track locations with a maximum accuracy

of about 8 meters, which means that

one will still have to search for the missing cat/dog/ferret/parakeet/guinea

pig/elderly/toddler/other within an area of approximately

200 meters. This is helpful

if that area is a mall or public park but becomes more complicated when it

concerns a crowded multistorey mall or dense forest.

Wearable GPS trackers are effective to the extent

that they can assist in keeping an eye on those we care for and help us to

track their location in precarious situations. In that sense, the technology

may effectively relieve some of the burden of care even if that relief rests on

the illusion of pseudo-safety. Whether their use is also desirable, however, depends on how users deal with the ethical

concerns around privacy, control, dignity, and autonomy that tracking devices

also unavoidably raise. Ultimately, the biggest issue is not if the trackers

work but how they affect the relation between ‘the tracker’ (i.e. parent,

owner, relative) and the tracked (i.e. child, pet, caregiver). The right to privacy

and self-determination is obviously less of an issue in the case of pet

trackers although some self-reflection on whether your paranoia is enough of an

excuse to make your dog “look

like a Silicon Valley asshole’s pet” seems fair. But if you are considering the option to equip your child

or dementing relative with a GPS tracker there are many other ethical concerns

to deliberate (Michael

et al 2006; Landau

2012; Estes

2014). Will you truly use the

wearable in the best interest of your beloved one, or are you simply being

tricked into buying yet another technological gadget that “resemble[s]

solutions in search of a problem” (Haggerty

and Ericson 2006: 14)?

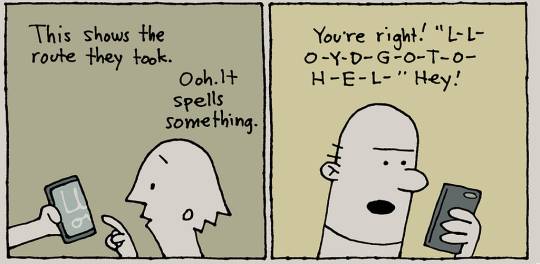

Image

flickr.com