door: Martje de Vries

Vorige week, op 2 maart, was het World Book Day. Zonder enige weet van

dit UNESCO-initiatief was ik op die dag in de Morgan Library & Museum in New York

City, waar een groepje zesjarigen een rondleiding kreeg. Toevallig ving ik het

begin van de rondleiding op: “I am going to show you Morgan’s collection today.

Does any of you know what a collection

is?” Vier handen gingen de lucht in: “It is when you get things, or you buy them,

and then you have a lot of them”. “That is an excellent definition. Now, who of

you has a collection?” Acht handen ditmaal, alle kinderen verzamelden wel iets: “Me and

my sister collect books and shells.” “That sounds

like a wonderful collection. Why do you collect books and shells?” “Because they make us

happy”.

De uitvinding van de boekdrukkunst heeft grote veranderingen in de

samenleving en maatschappij teweeggebracht. Niet alleen veranderde deze

uitvinding sociale en economische structuren en werden grote hoeveelheden

informatie goedkoper en dus toegankelijker en makkelijker te verspreiden; de

groeiende hoeveelheid boeken zorgde ook voor een (her)structurering van

archieven, universiteiten en bibliotheken.

Wetenschappers in de zestiende en zeventiende eeuw werden

geconfronteerd met een schijnbaar eindeloze informatiestroom, en werden

gedwongen om manieren te bedenken om daar grip op te krijgen – de overgang van

‘gedrukte handschriften’ naar (handzame) boeken met titelpagina’s,

inhoudsopgave, voorwoord en inleiding, index en zelfs flapteksten en recensies

ging niet over één nacht ijs – en datzelfde geldt voor vroegmoderne

archivarissen en bibliothecarissen die moesten bedenken hoe en waar al die

boeken verwerkt, opgeslagen en gelezen moesten worden.

Hoewel gevoelens van een overaanbod aan informatie dus niet een louter

eenentwintigste-eeuws fenomeen zijn, brengen de huidige digitale middelen de

afgelopen decennia veranderingen van soortgelijke grootte met zich mee in de

geesteswetenschappen. Het vrij nieuwe wetenschapsveld van de ‘Digital

Humanities’, waarvoor vrijwel niemand een Nederlands equivalent gebruikt,

gaat uit van het principe dat het gedrukte woord niet langer het voornaamste

medium is van kennisproductie en –verspreiding, en houdt zich onder meer bezig

met het ontwikkelen van manieren om grip te krijgen op de veelheid aan digitale

informatie.

Veel bibliotheken worstelen tegenwoordig niet alleen met

financiële bezuinigingen, maar ook met de mogelijkheden en moeilijkheden die

het digitale tijdperk biedt. Regelmatig gaan er stemmen op dat bibliotheken

mettertijd overbodig zullen worden. Het is natuurlijk geweldig dat bijna alle

informatie tegenwoordig (al dan niet tegen betaling) online toegankelijk is. Op

Delpher, kun je nu al miljoenen

gedigitaliseerde teksten uit Nederlandse kranten, boeken en tijdschriften doorzoeken

op woordniveau, en de database zal de komende jaren alleen maar groeien.

Daarnaast scheelt het enorm in ruimte als niet al die gegevens in een

bibliotheekkast bewaard hoeven te worden. Een vrijwilliger in de New York Public Library vertelde me beeldend

dat een stapel die opgebouwd was uit alleen het laatste exemplaar van elk

tijdschrift waarop NYPL geabonneerd is het Empire State Building in hoogte zou

overtreffen.

Maar dat alles altijd en overal digitaal raadpleegbaar is heeft

ook een keerzijde. Als alles digitaal beschikbaar is en iedere hippe koffiebar

tegenwoordig WiFi aanbiedt, waarom zou je dan nog naar de bibliotheek gaan? Het

is juist in deze omstandigheden dat bibliotheken hun waarde als meer dan

slechts een opslagplaats van informatie tonen. Wat is het dat die vrijwillige

enthousiaste rondleiders en de mensen die zelfs op zondag in de leeszaal zitten

aantrekt? Op de buitenmuur van de openbare bibliotheek van Princeton, waar ik af

en toe aan het werk ben deze maanden, staat een citaat van Borges (in het

Engels, weliswaar): “I have always imagined that paradise will be a kind of

library”. Een medestudent zei me afgelopen week ongeveer hetzelfde, maar dan

negatief geformuleerd: “Without the library I would feel awfully lonely here in

Princeton.” Ter gelegenheid van de World Book Day waar ik tot vorige week nooit

van had gehoord schreef kinderboekenschrijfster Nicola Davies in The

Guardian een

korte lofzang op de (openbare) bibliotheek en haar medewerkers, waarin ze stelt

dat deze een vitale rol vervullen in onze samenleving: “Without librarians and the libraries they make we are less alive, less

human, more profoundly alone”.

Toen ik zelf zes was, verzamelde ik niet alleen ook boeken en

schelpen, maar wilde ik tevens graag Belle uit Belle en het Beest zijn. Niet

omdat ik graag zoals mijn leeftijdsgenote Emma Watson op alle filmposters voor

de première van deze week wilde staan – die gele jurk staat haar, zoals

eigenlijk alles, veel beter dan mij – maar omdat ik zelf ook zo gelukkig zou

zijn met en in de bibliotheek (inclusief de globes en de houten trappen langs

de kasten) die ze krijgt in de Disneyfilm. De

mogelijkheden van digitalisering en digitale media zijn groot en groots, en het

effect is misschien wel van dezelfde orde van grootte als dat van de uitvinding

van de boekdrukkunst een krappe 600 jaar geleden. Maar tot op heden heb ik nog

nooit iemand horen zeggen er minder eenzaam of zelfs gelukkig te worden van een

collectie gedigitaliseerde boeken, en wat dat betreft zijn die zesjarigen de

beste bewijzen en ambassadeurs voor het behoud van fysieke boekencollecties – niet

in de laatste plaats vanwege de toevoeging van schelpen.

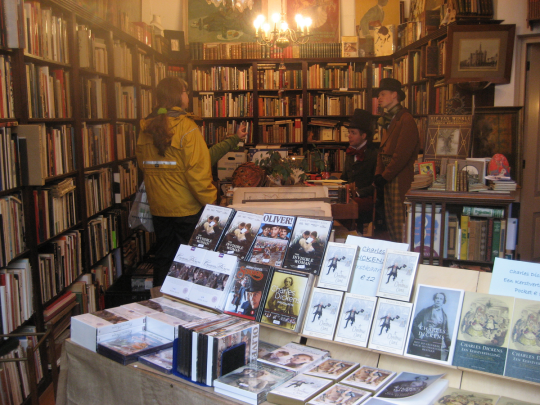

Foto: Morgan Library & Museum (foto: Martje de Vries)