Written by Elisa Fiore

TRIGGER WARNING: The first part of this post refers to war

violence.

View on the Monte Sole Historical Park, Bologna – © E.Fiore, December

2017

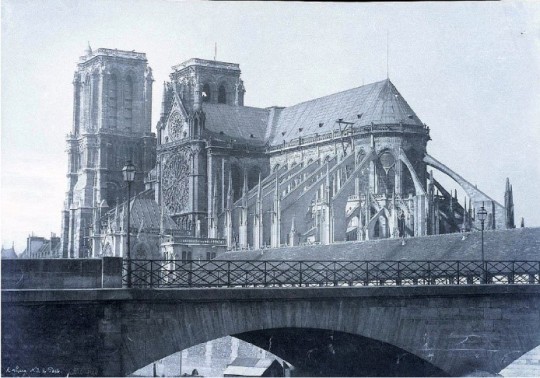

I started writing this blog post on the 29th of September 2019, the 75th anniversary of the massacre of Monte Sole – also known as the Massacre of Marzabotto – on the Apennine mountains south of Bologna. The massacre went down in history as the largest and most heinous massacre of civilians carried out by Nazi and Fascist troops during the war, and the deadliest mass shooting in the history of Italy. At least 775 people were killed in this six-day reprisal, mostly children, women, and the elderly. Towards the end of WWII (1943-45), the area of Monte Sole was traversed by the so-called Gothic Line, the last major fortified defensive line of the German army, which ran for 300km from the Tyrrhenian to the Adriatic coast following the rugged contours of the Apennine reliefs. The Gothic Line was one of the main theatres of the Italian Liberation War, with the Partisan Movement

engaging in systematic attacks and sabotage against the retreating German

forces and their Fascist allies.

The Monte Sole area was the territory of the partisan brigade Stella Rossa (Red Star), which was founded in September 1943 after the Armistice of Cassabile. Stella Rossa was deeply rooted in the territory and the civilian population was on the whole very favourable to their activities, which they supported by providing clothes, food, hiding places, and possibly shelter in barns and stables. The brigade was led by Mario Musolesi aka “il Lupo” – the wolf – a very respected 29-year-old former-mechanic, whose fame and reputation contributed to the growing success of the Resistance Movement in Monte Sole – the acknowledged partisans acting in the brigade were 1.538 (City of Bologna). In the summer of 1944, Stella Rossa pulled off several successful attacks against the retreating German army, blowing up train lines and roadways, but also resisting for months all German attempts to break into the Monte Sole territory. It is precisely as a reprisal to these attacks that the massacre was organised.

On the 29th of September 1944, SS-Sturmbannführer Walther Reder led the

XVI Panzer Grenadier Division “Reich Führer SS” into Monte Sole armed with

heavy artillery and started raiding schools, farmsteads, churches, and houses with a scorched earth approach. No one was spared. In 1945, Reder was captured by the British Army in Austria. He was tried in 1951 by the Bologna Military Court, who sentenced him to life imprisonment for war crimes.

Today, Monte Sole has been turned into a historical park stretching over 6.300 hectares, whose ‘primary objective, along with the conservation and valorisation of the environmental heritage, is to promote a culture of peace aimed to future generations’ (Scuola di Pace Monte Sole). Inside the park, the Memorial Trail leads visitors through the symbolic places of the 1944 massacre, and each 25th of April – the Italian Liberation Day – thousands of people gather here from Bologna and the surrounding areas to walk the Memorial Trail together to the sound of the marching bands playing Resistance songs.

Stella Rossa commemorative stone – © E.Fiore and L.Di Maio, 25th of April

2018

At the summit of the Memorial Trail, there is a commemorative stone that was placed there in 1953 as a memorial to the hundreds of victims of the massacre. The stone is topped by a red star, an explicit dedication to the local partisan brigade, and at the bottom of the inscription a red seemingly-hand-written carving that says “W il Lupo”, in honour of the

brigade leader who also died during the massacre. Every 25th of April, people gather around the commemorative stone, singing “Bella Ciao!” at

the top of their lungs, and thus honouring the memory of all those who died to oppose Nazi-Fascism. Being there on such occasion literally moved me to tears.

Why am I telling you all this?, you might be wondering. Let’s just say that this issue – that of Anti-Fascism – has been occupying my mind for the last couple of weeks at least. On the 18th of September 2019, the European Parliament issued the joint resolution 2019/2819(RSP) titled “On the Importance of European Remembrance for the Future of Europe” –

which can be read in full here: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/RC-9-2019-0097_EN.html. Backed by the S&D (centre

left), Renew (liberal), EPP (Christian-Democrat), and ECR (conservative)

groups, this motion wants to be a condemnation of all “totalitarianism” and

identifies the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 as the starting point of WWII. In this resolution, the European Parliament condemns communism as equivalent to Nazism. In their words, ‘The European Parliament [… r]ecalls that the Nazi and communist regimes carried out mass murders, genocide and deportations and caused a loss of life and freedom

in the 20th century on a scale unseen in human history, and recalls

the horrific crime of the Holocaust perpetrated by the Nazi regime; condemns in the strongest terms the acts of aggression, crimes against humanity and mass human rights violations perpetrated by the Nazi, communist and other totalitarian regimes’. The Parliament also writes that they condemn ‘all manifestations and propagation of totalitarian ideologies, such as Nazism and Stalinism, in the EU’, and call for ‘a common culture of remembrance that rejects the crimes of fascist, Stalinist, and other totalitarian and authoritarian regimes of the past as a way of fostering resilience against modern threats to democracy, particularly among the younger generation’.

As easily imaginable, this resolution has split the political world, and the political left in particular. While the (far-)right exults, many leftist politicians and commentators are outraged by the document. As they argue, equating Nazism and communism implies presenting communism as fundamentally genocidal. British historian David Broder (2019) points out

that, by constantly confusing the political and the ideological planes (Stalinism vs communism), ‘the European Parliament condemns not only Stalinist atrocities, but the entire experience of state socialism — and even the communists who opposed Stalin — as equivalent to the Nazis and their death camps’. Moreover, the resolution has been judged as a historical false, in that it reduces WWII to a Nazi-Soviet division of Europe, turns a blind eye to the responsibilities of all European liberal democracies in the outbreak of the war, and erases the fact that Russia was at once one of the main victims of the conflict with 27 million casualties and one of the main actors in fighting Nazism. Italian commentators in particular have pointed out that, by equating Communism with Nazism, the European Parliament has legitimised the already widespread “reversist” (D’Orgi 2019) arguments used by the (far-)right, which equate the Italian Resistance Movement – often inspired by communist and socialist values and ideals – to the Fascist regime they strenuously opposed. According to these commentators, the resolution is a gift horse to the (far-)right in Italy and elsewhere – the same far-right that the European Parliament intends to counter with this very resolution.

I am not fully qualified to judge the validity of the above critiques. But I have to admit that there are a couple other passages in this motion that I find extremely worrying. A little later in the document, the Parliament ‘[e]xpresses concern at the continued use of symbols of totalitarian regimes in the public sphere and for commercial purposes, and recalls that a number of European countries have banned the use of both Nazi and communist symbols’. They also note ‘the continued existence in public spaces in some Member States of monuments and memorials (parks, squares, streets etc.) glorifying totalitarian regimes, which paves the way for the distortion of historical facts about the consequences of the Second World War and for the propagation of the totalitarian political system’. For this reason, the Parliament ‘[u]rges the Member States […] to counter organisations that spread hate speech and violence in public spaces and online’. By once again validating the common misconception that conflates communism with Stalinism, the European Parliament appears to open the door for the criminalisation of all communist symbols (even the pop-culture ones) and organisations, and de facto urges Member State to eliminate them.

At the moment, the resolution is not binding for Member States. But let’s imagine for a moment it was. What consequences would it have? Would many of the symbols, monuments, and memorials commemorating the victims of Nazi-Fascism or the Anti-Fascist Resistance disappear? Would for example the Soviet War Memorial in Großer Tiergarten in Berlin, dedicated to Russian victims of WWII, have to be torn down? Would all street names dedicated to communist figures like Rosa Luxemburg or Antonio Gramsci, to name but two, need to be named after “more neutral” or “less controversial” figures? And what about all the plaques and memorials dedicated to the partisans who died in the Resistance, would they also need to go? What would happen, for example, to those workers unions that have served for many workers as spaces of self-awareness and resistance against capitalist exploitation? And the t-shirts with the face of Che Guevara, or the hats with a red star, would they be withdrawn from the market? And the people who wear them, would they be fined or arrested? Would the yearly 25th of April gathering in Monte Sole be eliminated?

And would we still be allowed to sing Bella Ciao?

For the time being, these are just some provocations. But what if we really were to wake up in a world where Anti-Fascism is a crime and the Nazi Holocaust just another evil among many rather the lowest point in European 20th century history? As Hannah Arendt (1963) wrote, ‘[c]ertainly fascism has already been defeated once, but we are far from having definitively eradicated this supreme evil of our time’.

Therefore, W la Resistenza e W il lupo!

To know more:

For those who want to know more about Monte Sole, I recommend that they watch the film The Man who will Come, by Italian director Giorgio Diritti (2009). It was awarded several David di Donatello Awards (for Best Film, Best Producer, and Best Sound) and many other film awards. In its original version, the film is in Bolognese dialect with Italian subtitles, a unique occurrence in Italian cinematography. Here is the trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o8D7Coxba4I

Here is also a nice video on the Monte Sole Historical Park made by Lab051: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=252&v=OxN5cAO_2U0

——-

References

Arendt, Hannah. 1963. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.

Broder, David. 2019. The End of Anti-Fascism. Jacobin – https://jacobinmag.com/2019/09/european-parliament-nazism-communism-russia-viktor-orban

Cararo, Sergio. 2019. L’anticomunismo diventa regola delle istituzioni europee. Contropiano – http://contropiano.org/news/politica-news/2019/09/20/lanticomunismo-diventa-regola-delle-istituzioni-europee-0118896

Conti, Davide. 2019. La storia stravolta a propaganda dal parlamento europeo. Il Manifesto – https://ilmanifesto.it/la-storia-stravolta-a-propaganda-dal-parlamento-europeo/

Corsetti, Carla. 2019. Stalin come Hitler e Mussolini? A chi giova la risoluzione UE che equipara il comunismo al nazifascismo. Left – https://left.it/2019/09/22/stalin-come-hitler-e-mussolini-a-chi-giova-la-risoluzione-ue-che-equipara-il-comunismo-al-nazifascismo/?fbclid=IwAR3w60sbEmhYF53WYseO3suvn1np4pT63PVVYNv4H4nV8gb1J-uyS4z8IzU

D’Orsi, Angelo. 2019. Comunismo come nazismo? Un mostro storico e una bestialità politica MicroMega – http://temi.repubblica.it/micromega-online/comunismo-come-nazismo-un-mostro-storico-e-una-bestialita-politica/

European Parliament. 2019. European Parliament resolution on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/RC-9-2019-0097_EN.html

Maringiò, Francesco. 2019. European Parliament adopts resolution assimilating Communism to Nazism. Global Research – https://www.globalresearch.ca/european-parliament-adopts-resolution-assimilating-communism-nazism/5689849

Milne, Seuma. 2019. The rewriting of history is spreading Europe’s poison. The Guardian – https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2009/sep/09/second-world-war-soviet-pact

Storia e Memoria di Bologna, website – https://www.storiaememoriadibologna.it/eccidio-di-monte-sole-54-evento