By Julia Neugarten

Writing is the bread and butter of the humanities scholar. It is our chisel and our marble, our raison d’être, and yet the bane of our existence. With the daunting task of writing a dissertation in the forefront of my mind, I was curious about my colleagues’ writing habits, and so I circulated a questionnaire among the employees of the department of Arts and Culture Studies at Radboud University. The response I got was inspiring and insightful, and whether you’re a student or a scholar, a poet or a playwright, some of it may be helpful to you as well.

How much do we write?

Twelve people responded to the survey. On average, they spend 226 minutes per week writing, or a little under four hours.1 The amount of weekly writing time per person varies by a lot, ranging from 60 to 750 minutes. Together, these 12 people spend 45 hours per week writing.

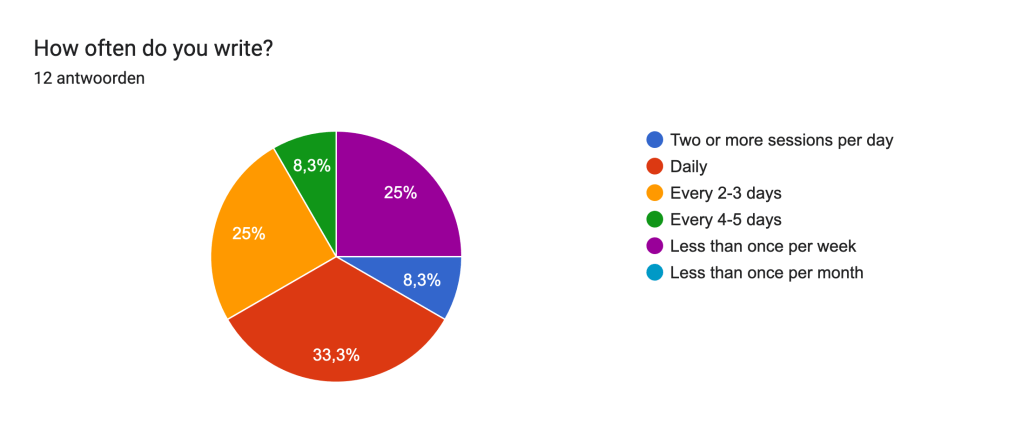

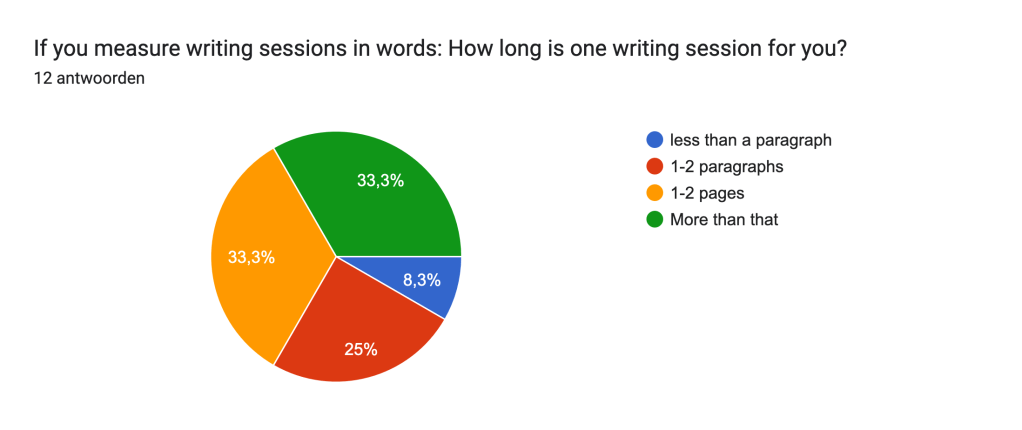

Some people measure writing in time and others measure it in output, so the questionnaire asked about both. Conventional wisdom holds that it is best to write every day,2 and about one-third of respondents do. Shout-out to the person who manages multiple writing sessions per day.

When comparing writing time to word production, interesting differences emerge. One respondent estimates that their writing sessions take longer than 2 hours and results in less than one paragraph of writing. Another estimates that they produce more than two pages in a session of under 30 minutes. Of course these questions do not account for the quality of the writing, or how much actually ends up getting published. This is purely about production.

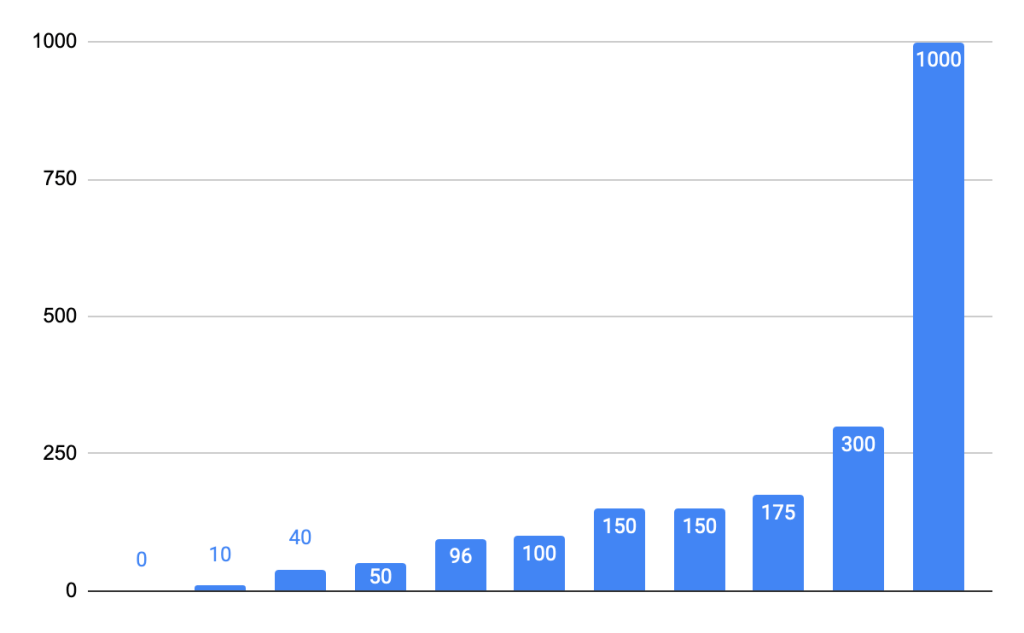

I also asked: How many pages of academic text do you estimate you have written in the past year, assuming a page is around 250 words?3 Here’s the reported response in pages, with each bar representing one respondent.

Notably, the person who estimated their output at 1000 pages a year (actually, their response was ‘more than 1000 pages’) also reported that they were not happy (2 out of 5) with how much they wrote.

How do we feel about writing?

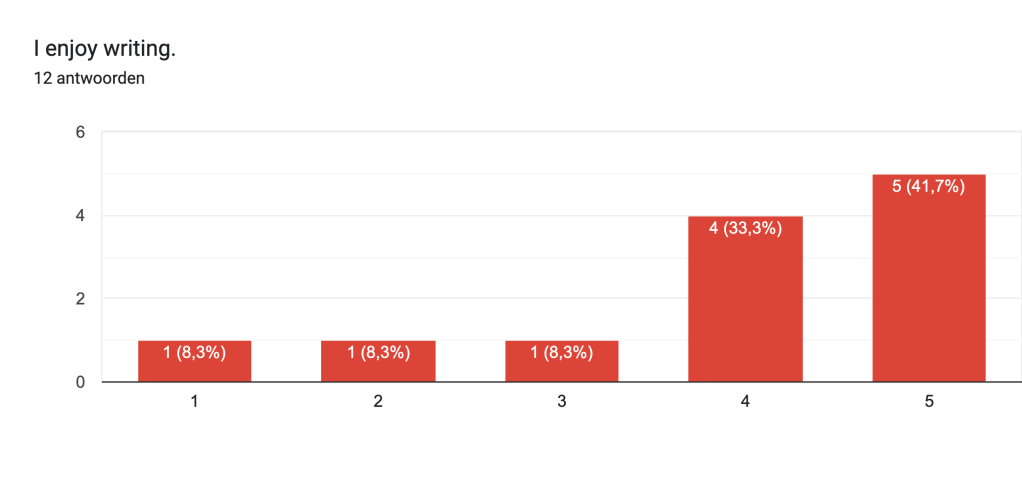

Fortunately, most respondents report that they enjoy writing.

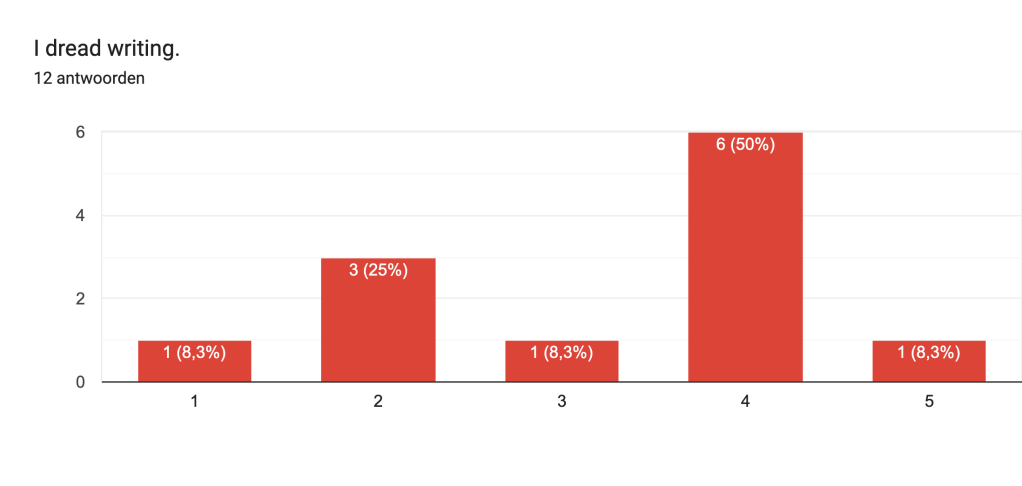

Meanwhile, more than half also report that they dread writing. For example, the person who said they enjoy writing not at all identifies the following phases in their writing process:

pain. agony. suffering. killing. relief.

Interestingly, 4 respondents (1/3) dread and enjoy writing approximately in equal measure, reporting a score of 4 or 5 in response to both questions.

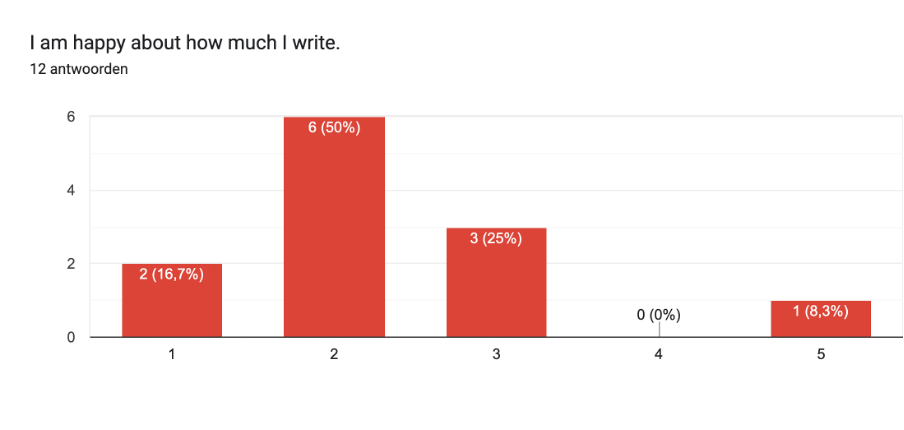

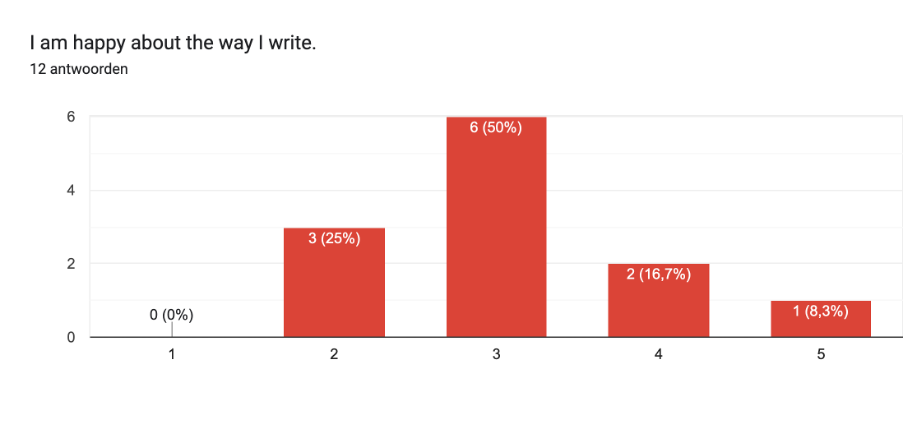

Around 3/4 of respondents are not very happy about how much they write, although most are at least moderately satisfied with how they write. The numbers on writer’s block are pretty spread out, although those who experience a lot of writer’s block also, unsurprisingly, report lots of dread around writing.

What are our writing techniques and processes?

I was curious about the strategies my colleagues used to get their writing done, and the steps they followed to structure the writing process. Many people mentioned that hot beverages, isolation and frequent exercise were key to getting them writing. The Pomodoro Method, where you alternate between 25-minute writing sprints and short breaks, was praised twice for boosting productivity.4

I was happy to see that I’m not the only one who feels like successful writing requires some kind of ritual to get you into the appropriate mindset. Someone reports that they need to:

block a whole day at a time (otherwise no way of getting into the ‘mood’)

Another respondent uses music to set the right atmosphere:

I have a playlist that is always the same so that I don’t REALLY hear it. I sometimes alternate music styles because the rhythm of the beat impacts the way that I think and write.

Many respondents say it can feel intimidating to start writing. For one writer, Word feels too ‘official’ and so writing on paper in the initial stages is a good way to lower the threshold. Interestingly, they also describe a Google Doc as less intimidating than a Word document.

Outlining is also mentioned as a good way to get rid of the empty page, and someone reports:

I tend to “trick” myself and write pieces in bits and bobs.

When it comes to the best order for writing and revising, responses are mixed. Some people write their texts from beginning to end, saying:

[I] can only move on to the next section of text if all earlier paragraphs are as complete and finished as I can make them.

Other people write the conclusion first, or write from beginning to end except for the introduction, which they save for last. Some people do not adhere to a linear order at all during writing. One piece of advice I particularly like is the idea to see the structuring of a text and its writing as carried out by two separate entities:

With pieces that I find really difficult to write I will write an outline where I briefly state which point I want to make in each paragraph so that I separate the role of opdrachtgever and uitvoerder of my own writing: I first write myself an outline, and then I pretend that I’m just the writer who was hired to execute it wether they agree or not.

This quote also touches on the next question I asked: Do you view writing and research as separate tasks? Most people answered yes to this question, although there were a couple of firm ‘no’s’ – like the person who says: “Writing is thinking. Writing is research” – and some people were unsure. Personally, I like this view:

Writing is about communicating results, not about creating results.

This separation lets us see the craft of writing as a separate academic skill, which I find valuable. Another respondent explains:

[Research and writing are] not neatly separated in time: once I start trying to write a final text I’ll discover along the way that I need research for specific steps in my thought process. So in practice they may seem to blend, but I regard them as separate sometimes very quickly alternating activities. Also: my experience is that writer block is what happens when you lose control over the difference between research, thinking and writing, and between writing and editing. It is, in my personal practice, important to be able to write horrible first drafts.

So the separation of writing and research seems productive to many. Nonetheless, I find it useful to think of writing as the material process through which scholarly research comes into being, especially in the humanities. That idea is described elegantly by one of the respondents who says no, writing and research are not separate:

my keyboard is my laboratory, this is where I atomise my data and pour them in textual flasks to see which ingredients react under which conditions.

Writing Advice: the Best and the Worst

Finally, I asked respondents about the best and worst writing advice they ever received. Most good advice mentioned the discipline to write every day, and a variety of methods for lowering the threshold on writing, so that writing every day became easier. Those tips included, for example: outlining first, lowering one’s own expectations about the quality and elegance of the first draft, starting to write at whatever point in the text is already clear to you. Similar advice is communicated in motto’s like “Done is better than perfect.” and “The best PhD is the Submitted PhD.” In other words: the perfect is the enemy of the good.

There’s one more piece of advice that I really like, and might write on a sticky note to keep by my desk:

Some of my most productive writing has been when I felt the joy of making discoveries and communicating my findings. Keep the joy!

Overall, what people mentioned as bad advice was often the inverse of what they considered good advice: perfectionism, especially. But some core values about the societal role of academic writing also came out in response to this question:

Writing styles are not neutral choices – they also communicate an intent and what I dare call a “vibe”. We are trying to communicate and collaborate – I’m not a fan of taking writers who’s style is hermetic or hostile towards more naïve readers as role models. Also, writing may seem like a solo activity, but I believe that at it’s core academic writing is a deeply social and collective activity: we write it down for others to take apart and re-use. (…) as academic writers we are pretty much valuable precisely to the extent that we make ourselves available to being cited and re-purposed for someone else’s research. So any advice that places to much emphasis on writing as the work of a Lone Genius Having Ideas does not make sense to me.

In a similar vein, someone observes:

Worst advice: writing is is method to order your own thoughts. It isn’t. It is a method to order the readers’ thoughts.

To conclude: in this piece, I’ve tried to order my own thoughts about the writing processes of my colleagues, and in the process I hope I have also helped you order yours. I’m going to experiment with writing academic texts in a different order, and I wish you all happy writing!

If you want to examine every response in detail, you can consult the full results of this year’s Arts and Culture Studies Writing Questionnaire here, with my added calculations in bold.

Footnotes

- Full disclosure: I myself am one of the 12 respondents. ↩︎

- Authors credited with this advice include Ray Bradbury, Stephen King, Graham Greene and Eric Hayot, the author of The Elements of Academic Style whose insights on academic writing inspired me to

create this survey. ↩︎ - I removed one respondent from the dataset here, who reported 12.500 pages. That must have been a typo, or maybe they meant words instead of pages. Otherwise it would be 3.125.000 words. For comparison, depending on the translation, War & Peace is between 560.000 and 587.000 words. I don’t think anyone is writing 5.5 copies of War and Peace per year, but if you’re the respondent and this is actually accurate, let me know. I’d love to interview you. ↩︎

- The Pomodoro Method was invented by Francesco Cirillo. ↩︎