Dit stuk is van Holly van Zoggel, tweedejaars bachelorstudent Algemene Cultuurwetenschappen aan de Radboud

Speelse verkenningen van de mogelijkheden en beperkingen van kunst kenmerken het oeuvre van Ali Smith. De Schotse auteur, geprezen om haar experimentele romans en korte verhalen, gaat in haar teksten regelmatig relaties aan met andere, niet-literaire kunstvormen. Met name schilderkunst en fotografie zijn op verschillende niveaus met haar werk verweven: niet enkel in de vorm van ekfrasis – de literaire beschrijving van een visueel kunstwerk – en fysieke integratie van beeldmateriaal, maar ook via de toepassing van concepten en conventies van beeldende kunsten in het geschreven woord. In How to Be Both (2014), dat bekroond werd met de Costa Novel of the Year Award en de Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, vervullen de fresco’s van renaissanceschilder Francesco del Cossa een centrale rol. Smith reflecteert op de eigenschappen van deze werken en trekt hun mediumspecificiteit in twijfel door te onderzoeken in hoeverre ze over te hevelen zijn op de romanvorm. Schrijvend in het spanningsveld tussen media tracht ze de grenzen van literatuur te herzien. Mijn analyse is toegespitst op het narratieve en poëtische experiment met een typisch verschilpunt tussen de beeldende kunst en het geschreven woord: hun relatie tot het verstrijken van de tijd.

How to Be Both vertelt de verstrengelde hedens en verledens van Francescho – een personage dat gebaseerd is op de historische figuur Francesco del Cossa, over wiens leven weinig bekend is – en de eenentwintigste-eeuwse tiener George. De roman is opgedeeld in twee secties, waarvan de een het perspectief van George en de ander dat van Francescho als vertrekpunt neemt. Hun verhalen ontmoeten elkaar in een ongedefinieerde ruimte waarin tijd tijdloos wordt en lichamen hun materialiteit verliezen. Francescho wringt zich door eeuwen en aardlagen heen om als spookachtige aanwezigheid in de eenentwintigste eeuw terecht te komen. Hij vindt zichzelf in een purgatorium, schijnbaar gesitueerd in de Londense National Gallery, waar George een van zijn schilderijen geconcentreerd bestudeert. Het zestienjarige meisje – dat door Francescho in eerste instantie voor een jongen wordt aangezien – is zich van zijn aanwezigheid niet bewust. Haar aandacht wordt opgeëist door haar moeder Carol, die enkele maanden eerder overleed, maar via herinneringen in de tegenwoordige tijd lijkt door te leven.

Met schilderkunst als model speelt het boek met de temporele conventies van literair narratief. Ik tracht in kaart te brengen hoe Ali Smith de mogelijkheden en beperkingen van taal en literatuur zowel herkent als verlegt. Ik onderzoek de manieren waarop de roman losbreekt van lineariteit en uitdrukking geeft aan de simultaniteit van verschillende tijdlijnen. Hierbij vraag ik me steeds af hoe dit formele experiment zich verhoudt tot de centrale thema’s van het boek. Hoe literatuur het voortduren van het verleden in het heden kan verbeelden. Hoe taal tekortschiet of juist toereikend is in het verwerken van verlies. Hoe woorden in staat zijn herinneringen te koesteren.

Read more: Literaire Fresco’s: Verbeeldingen van gelijktijdigheid in Ali Smiths How to Be Both (2014)Intermedialiteit

Ali Smith is zich er als geen ander van bewust dat media nooit in isolement, maar altijd in relatie tot elkaar bestaan. Haar begrip van intermedialiteit is te categoriseren volgens de terminologie van Irina Rajewsky. De Duitse literatuurwetenschapper onderscheidt twee brede opvattingen. Enerzijds intermedialiteit als een fundamentele categorie, waarbinnen invloeden van verschillende media met elkaar versmelten tot een onlosmakelijk geheel. Anderzijds intermedialiteit als kritische categorie voor de concrete analyse van individuele mediaproducten (Rajewsky 47). Ik benader How to Be Both vanuit deze tweede opvatting, meer specifiek gericht op wat Rajewsky bestempelt als “intermediale referenties”. Hierbij gaat het om de manieren waarop een medium zichzelf herziet door zich op te stellen tegenover een ander medium: “Rather than combining different medial forms of articulation, the given media-product thematizes, evokes, or imitates elements or structures of another, conventionally distinct medium through the use of its own media-specific means” (Rajewsky 53). Deze vorm van intermedialiteit is gebaseerd op het idee dat de kunsten essentiële, mediumspecifieke karakteristieken hebben. Hiermee wordt een zekere hiërarchie verondersteld: wanneer bepaalde procedés en technieken uitdrukkelijk de schilderkunst toebehoren, is de overheveling hiervan naar literatuur een beweging van centrum naar periferie. Dit hiërarchische denken voelt enigszins misplaatst met betrekking tot How to Be Both, een werk waarin juist grenzeloosheid en fluïditeit – van onder meer media, gender en tijd – centraal staan. Sporadisch zal ik dan ook uitlichten waar beschrijvingen van schilderkunst geïnformeerd lijken door literaire eigenschappen. De nadruk, echter, ligt op de roman als verkenning van wat literatuur is en kan doen.

Simultaniteit en gelaagdheid in schilderkunst

Hoe verhoudt een medium zich tot de tijd? De diverse temporele dimensies van schilderkunst en literatuur kunnen worden gezien als een belangrijk verschilpunt tussen beide media. In “Art and Temporality” noemt C.D. Keyes simultaniteit als kenmerkende eigenschap van de beeldende kunst: “Graphic art-works are there all at once, and when we stop looking at them they still exist” (65). Een schilderij heeft geen afgebakend begin en eind, en bestaat daarmee relatief onafhankelijk van de tijd. Het medium is in staat om de gelijktijdigheid van verschillende visies uit te drukken in een enkel, eeuwig voortdurend moment. Hiertegenover staat de traditionele opvatting van literatuur als medium dat op veel explicietere wijze afhankelijk is van het verstrijken van de tijd. Een narratief veronderstelt een begin- en eindpunt en wekt hiermee de suggestie een afgesloten geheel te zijn. In plaats van simultaniteit staat sequentialiteit centraal: de lineaire opeenvolging van elementen die na elkaar plaatsvinden (Grabes).

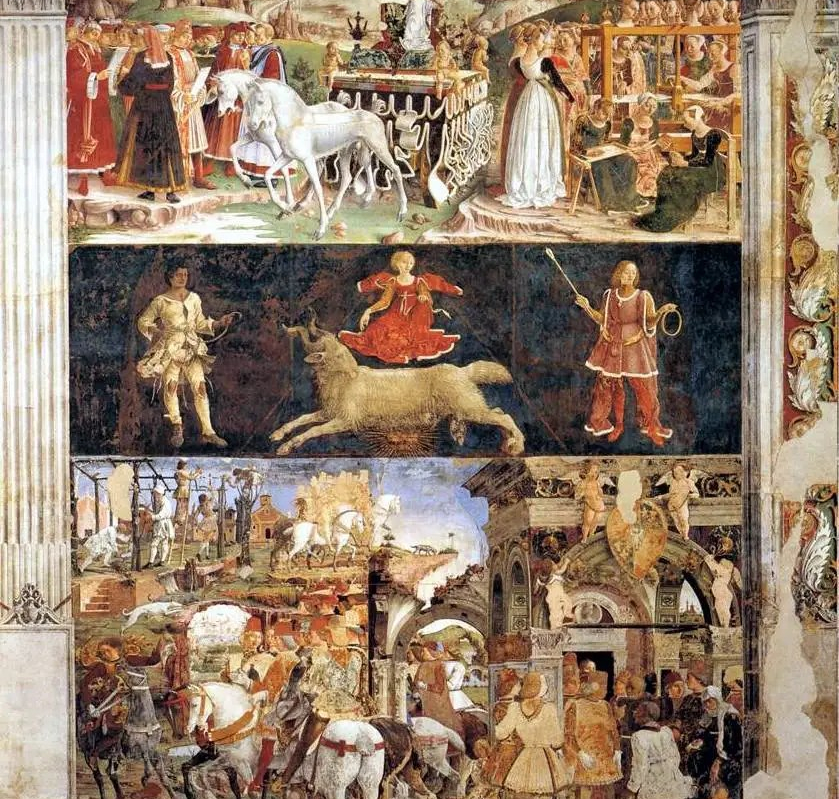

De schilderkunst van Francesco del Cossa loopt als een rode draad door How to Be Both heen. In Georges sectie lezen we hoe zij, met haar moeder en broertje, de bekende fresco’s van de Italiaanse schilder bestudeert. Later, na de dood van haar moeder, kan George zijn werk niet loslaten en bezoekt ze herhaaldelijk de National Gallery om Del Cossa’s enige schilderij op Engelse bodem grondig onder de loep te nemen. Via ekfraseis, soms meerdere pagina’s lang, wordt de lezer geconfronteerd met de ervaringen van George: onze beeldvorming van de schilderijen is afhankelijk van wat zij de moeite waard vindt uit te lichten. Francescho’s sectie biedt een alternatief perspectief door een voorstelling te geven van de kunstpraktijk waarin deze werken tot stand zijn gekomen. De schilderijen vormen bovendien gespreksstof voor de uitvoerige discussies tussen George en Carol over het doel van kunst. Het prominentst aanwezig zijn de verwijzingen naar “Hall of the Months”, de frescocyclus die Borso d’Este in 1471 liet maken in Palazzo Schifanoia na zijn inauguratie als hertog van Ferrara. Het werk toont de nieuwe hertog als hoofdpersoon in twaalf scènes die de maanden van het jaar voorstellen. Del Cossa was verantwoordelijk voor de uitvoering van maart, april en mei. Iedere maand is horizontaal in drie lagen verdeeld: de bovenste is gereserveerd voor mythische goden, de onderste verbeeldt fragmenten van d’Estes leven en de middelste is een blauwe band, als een lucht, gevuld met astrologische figuren. Met zijn speelse extravagantie en gestileerde ornamentatie is het werk exemplarisch voor de Ferrarese school, een vertakking van de schilderkunst in het Quattrocento waartoe Del Cossa veelal gerekend wordt (Manca 55-56). Wanneer George deze zaal voor het eerst betreedt, omschrijft ze die als “so full of life that it’s actually like life” (Smith 49). Dit leven laat zich niet rangschikken in een narratieve sequentie van gebeurtenissen: de verschillende scènes komen tegelijkertijd tot leven, als een visuele kakofonie. Georges beschrijving van de frescocyclus bestaat uit een willekeurige opeenvolging van details die toevallig de aandacht trekken: “There are dogs and horses, soldiers and townspeople, birds and flowers, rivers and riverbanks, water bubbles in the rivers, swans that look like they’re laughing” (50). Het lijkt ondoenlijk om de overdonderende ervaring van beelden die gelijktijdig binnenkomen te vangen in de logische samenhang van een literair narratief.

De simultaniteit van de schilderkunst die hiermee wordt geïllustreerd sluit de mogelijkheid van narratief echter niet compleet uit. Francescho spreekt meermaals over het maken van een schilderij als het vertellen van een verhaal. Zijn geschilderde verhalen zijn niet op één correcte, sequentiële wijze te vatten, maar omarmen het simultane, de gelaagdheid van verschillende versies van de werkelijkheid die zich gelijktijdig ontvouwen: “I learned . . . how to tell a story, but tell it more than one way at once, and tell another underneath it up-rising through the skin of it” (237). Ook George merkt deze gelaagdheid op:

It is like everything is in layers. Things happen right at the front of the pictures and at the same time they continue happening, both separately and connectedly, behind, and behind that, and again behind that, like you can see, in perspective, for miles . . . The picture makes you look at both – the close-ups happenings and the bigger picture. (Smith 53)

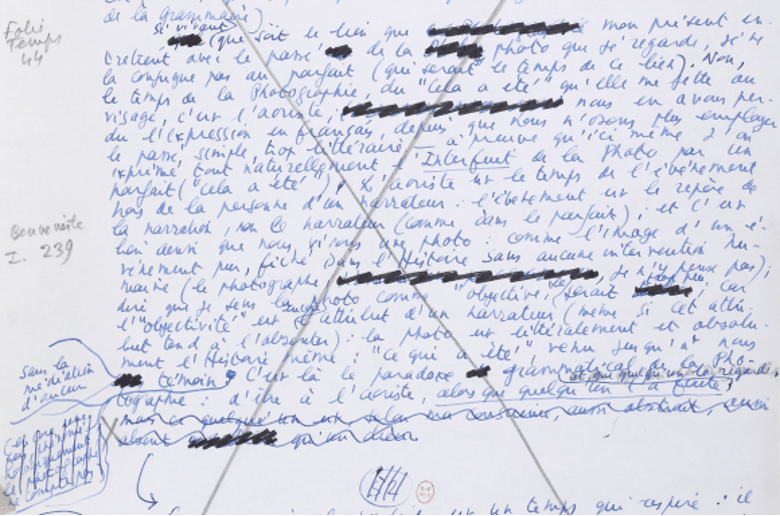

Het boek reflecteert expliciet op de uitzonderlijkheden van de frescotechniek in een gesprek tussen George en haar moeder. Carol vertelt over fresco’s die door een overstroming deels beschadigd zijn geraakt, waarbij de bovenste laag weggespoeld werd en de originele tekeningen tevoorschijn kwamen. Deze schetsen weken soms aanzienlijk af van het uiteindelijke werk. Vanuit deze anekdote vraagt ze zich af wat er eerst kwam: het beeld dat we zien, aan de oppervlakte, of het beeld dat daaronder bestaat. Hoewel George stellig antwoordt dat de ondertekeningen eerst kwamen – “because it was done first” – verdedigt haar moeder ook de andere kant: “the first thing we see . . . and most times the only thing we see, is the one on the surface. So does that mean it comes first after all? And does that mean the other picture, if we don’t know about it, may as well not exist?” (103). De gelaagde structuur van de fresco’s kan worden gezien als metaforisch model voor de narratieve opbouw van de roman zelf. In een essay over de totstandkoming van How to Be Both schrijft Ali Smith hierover:

I’d liked the notion that those first drawings had been there, unseen all along under the wall surface, which is, after all, what fresco is, an actual physical part of the wall. I’d been wondering if it might be possible to write a book consisting of something like this structure of layer and underlayer, something that could do both. (Smith “‘He looked’”)

Door de “temporally paradoxical relation of surface and depth” van de fresco’s als model te nemen voor de literatuur, daagt Smith de sequentiële narratieve vorm van de traditionele Europese roman uit (Huber en Funk 158). Aan de hand van de simultaniteit en gelaagdheid van Del Cossa’s schilderkunst gaat ze op zoek naar manieren waarop ook literatuur synchroniciteit kan verbeelden.

Wederkerige raamvertelling

De twee delen van How to Be Both zijn op ingenieuze wijze met elkaar verweven. Hoewel iedere sectie vertrekt vanuit het oogpunt van een van de karakters, bewegen Francescho en George zich ongedwongen tussen de verschillende tijdlijnen. Hun persoonlijke verhalen kennen veel overeenkomsten en weerklinken als echo’s van elkaar. Waar de levens van schilder en puber overlappen, versmelten verleden en heden in een “intermediate space” (Smith 225). De wisselwerking tussen de twee secties is als een spel met de conventionele sequentialiteit en causaliteit van narratief. Elk verhaal staat op zichzelf, maar kan ook gelezen worden als “extension or embedded feature of the opposite tale” (McCartney 332-333). Mary McCartney gebruikt de term “reciprocal frame narrative” om deze wederkerigheid en uitwisseling te definiëren. Waar in een klassieke raamvertelling het ene narratief niet kan bestaan zonder het kader van het andere, ontkent de wederkerige raamvertelling deze hiërarchische verhouding (331). Dit impliceert dat geen van beide gezien kan worden als centraal of primair (333). Ali Smith heeft dit egalitaire principe ver doorgevoerd door de helft van de boeken te laten publiceren met Georges deel als beginpunt, en vice versa. Het feit dat beide delen “one” getiteld zijn, is bovendien een weigering om chronologie aan te brengen. De verhalen van George en Francescho worden even belangrijk geacht en kunnen evengoed dienen als instappunt in het boek. De roman bestaat niet in één correcte vorm, maar presenteert de mogelijkheid van verschillende versies van de werkelijkheid. Net als bij de fresco’s en hun ondertekeningen bestaat er geen uitsluitsel over welke laag als eerst kwam.

Welke versie van het boek je openslaat, is volkomen willekeurig. Toch kan de volgorde waarin je de delen toegediend krijgt de leeservaring behoorlijk beïnvloeden. In hoeverre stuurt een verandering in chronologie de manier waarop je de twee narratieven in relatie tot elkaar begrijpt? Vragen als deze getuigen van de zelfreflexiviteit van How to Be Both. Doordat de auteur de rangschikkende macht deels uit handen geeft, wordt het lezende publiek in staat gesteld om de twee secties vanuit persoonlijke interpretaties aan elkaar te relateren. Zo kan wie Georges deel als eerste leest Francescho’s verhaal begrijpen als product van haar fantasie: “Francescho’s narrative brims with clues that it is, in fact, embedded within George’s imagination” (McCartney 338). Samen met haar vriendin H doet George onderzoek naar het werk en leven van Del Cossa. In hun gesprekken over de schilder vragen George en H zich af met welk vocabulaire hij gesproken zou hebben. Ze komen erachter dat het woord “ho” niet altijd betekende “what it means in rap songs”, maar ook een eeuwenoude uitroep van verrassing is (Smith 138). Dat Francescho vijftig pagina’s later zijn tumultueuze tijdreis naar de eenentwintigste eeuw inluidt met juist deze uitroep, lijkt hierdoor een knipoog naar George als agent achter de tekst.

“Present-time narration” en voortdurend verleden

Middels de wederkerige raamvertelling weet Ali Smith de grenzen tussen verschillende tijden te vervagen. De gelijktijdigheid van heden en verleden problematiseert het idee van een afgesloten narratief. Binnen Georges sectie wordt dit thema verder uitgewerkt, in relatie tot haar rouwproces. We leren George kennen op een duidelijk geankerd moment in de tijd: haar “nu” is de eerste Nieuwjaarsdag na haar moeders overlijden in september. Haar gedachten, echter, dwalen constant af van dit heden naar momenten waarop Carol nog in leven was. In het proces van herinnering lijkt George deze scènes opnieuw door te maken. Heden en verleden, realiteit en verbeelding, lopen in elkaar over, waardoor George nooit helemaal in het een of het ander is: ze bevindt zich in geen van beide en beide tegelijk. Deze onplaatsbaarheid wordt versterkt door een uniek gebruik van tijd en perspectief in de vertelling; we hebben te maken met “present-tense narration”, waarbij de vertellende handeling gesitueerd is in de tegenwoordige tijd. Volgens Eri Shigematsu gaat dit in tegen de natuurlijke vorm van vertelling, waarbij verleden tijd wordt ingezet om afgesloten gebeurtenissen te reproduceren (228). De “present-time narration” elimineert de temporele afstand tussen de twee dimensies van het narratieve tijdskader – enerzijds de “narrating time” waarin de vertellende handeling plaatsvindt, anderzijds de “narrated time” van de verhaalwereld waarin personages zich bewegen (228). Discours en verhaal zijn hierdoor nauwelijks van elkaar te onderscheiden. Hoewel het gebruik van de derdepersoonsvorm duidt op de aanwezigheid van een vertellende instantie, is het narratief volledig ingebed in het bewustzijn van George (235). Ze spreekt over het verleden als een actualiteit, wat maakt dat de grenzen tussen navertellen en ervaren vervagen.

Het narratief bestaat uit een wirwar van gefragmenteerde herinneringen die associatief in elkaar overvloeien. Deze gebroken structuur is te interpreteren als manier om de “temporele disruptie van rouw” te verbeelden (Gordon). Rouw vervormt de perceptie van tijd; Georges ervaringen van pijn en verlies lijken onmogelijk te vatten in een sequentiële vertelling en overstijgen de rationele conventies van lineariteit. Doordat ze de gesprekken met haar moeder in de tegenwoordige tijd herbeleeft, blijft Carol een aanwezigheid die voortduurt in het heden. Desondanks tracht George grip te krijgen op de werkelijkheid door zichzelf in het nu en haar moeder in het toen te situeren. Hardnekkig verbetert ze keer op keer haar eigen grammatica: “Not says. Said. / George’s mother is dead” (Smith 1). Haar noodzaak onderscheid te maken tussen heden en verleden komt voort uit een overtuiging dat de twee niet gelijktijdig en naast elkaar kunnen bestaan:

Because if things really did happen simultaneously it’d be like reading a book but one in which all the lines of the text have been overprinted, like each page is actually two pages but with one superimposed on the other to make it unreadable. (Smith 10)

In de loop van de roman stapt George af van deze drang naar temporele organisatie: “[she] eventually learns to appreciate such duplicity of looking at both, surface and depth, foreground and background” (Huber en Funk 162). Ze lijkt zich te realiseren dat het verleden niet ophoudt te bestaan, maar altijd weerklinkt in het heden. Net als de ondertekeningen van de fresco’s, zal wat geweest is niet verdwijnen wanneer het niet langer in zicht is.

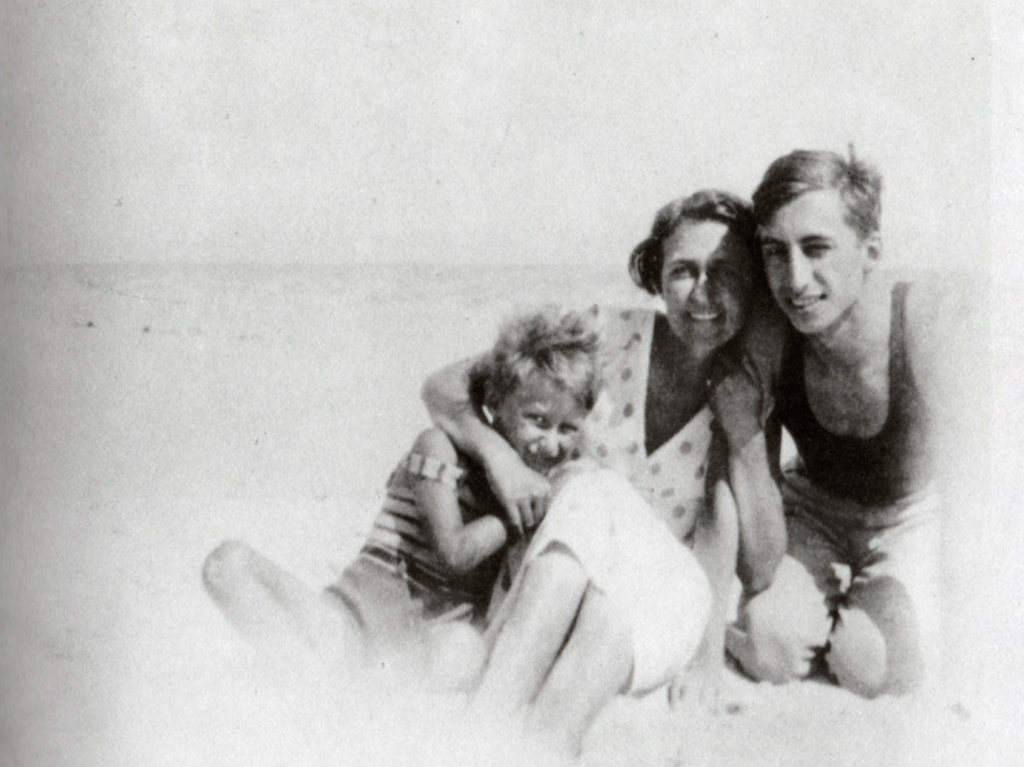

Dat George leert het simultane te omarmen, blijkt bijvoorbeeld uit de manier waarop ze foto’s van Carol in verschillende stadia van haar leven op de muur plakt: “she has arranged them so that there is no chronology” (Smith 45). Door lineaire rangschikking te vermijden, krijgt het leven van haar moeder geen gedefinieerd begin en eind; haar aanwezigheid blijft tijdloos voortduren. Francescho reflecteert op de samenstelling van deze foto’s: “there is love in their arrangement, they are an overwhelm in this arrangement, they fall almost into and over each other” (288). Zijn opmerking suggereert een link tussen liefde en simultaniteit. Enkele pagina’s eerder filosofeert hij nog explicieter over de relatie die zowel liefde als schilderkunst hebben tot de tijd:

[I]n the making of pictures and love – both – time itself changes its shape: the hours pass without being hours, they become something else, they become their own opposite, they become timelessness, they become no time at all. (Smith 273-274)

In Georges fotomuur herkent Francescho de potentie van schilderkunst om tijd te vervormen tot tijdloosheid. Hij beweert dat ook liefde in staat is om een aparte sfeer te creëren die losstaat van temporele beperkingen. In dit licht krijgen Ali Smiths pogingen om het gelijktijdige van de schilderkunst over te hevelen op de literatuur een duidelijke drijfveer: het verlangen om de liefde te laten voortduren.

Taal die tekortschiet en taal als herinnering

De simultaniteit van de schilderkunst manifesteert zich bovendien op het stilistische niveau van de roman. Dit is het best te illustreren aan de hand van het begin van Francescho’s sectie, een verslag van de wonderlijke reis die de schilder aflegt – dwars door barrières van tijd en ruimte, leven en dood – om in de eenentwintigste eeuw te geraken. De conventionele opmaak van de roman, waarin letters de pagina’s van linksboven tot rechtsonder vullen, wordt doorbroken: woorden wervelen als een draaikolk over het papier. Met zijn gefragmenteerde zinsbouw, opgehakt door enjambementen, vestigt de tekst de aandacht op zichzelf als tekst. Door dit gebruik van de poëtische functie verkrijgt literatuur de status van een object dat niet enkel temporeel, maar ook ruimtelijk ervaren kan worden. Francescho’s taalgebruik is opgejaagd, vluchtig. Halve zinnen volgen elkaar associatief op in een doorlopende stroom aan woorden, die hier en daar niet eens worden afgemaakt: “can hardly rememb anyth” (192). Het is alsof Francescho alle eeuwen die hij niet (bewust) heeft meegemaakt over de spanne van enkele pagina’s moet doorleven, waarbij hij onvermijdelijk wordt ingehaald door de tijd. De schilder wil alles tegelijkertijd vertellen, maar woorden blijken niet snel genoeg om zijn gedachten te vangen. Middels dit fragment wordt de lezer bewust gemaakt van de grenzen van taal: taal slaagt er niet in om, zoals schilderkunst, een ervaring van simultaniteit te vangen. Ali Smith reflecteert op de beperktheid van literatuur, een medium dat onvermijdelijk bestaat uit een sequentie van betekenaars in een discours.

De schrijfstijl in Francescho’s sectie reflecteert echter niet enkel op taal als vluchtig en temporeel, maar laat ook zien dat taal een continuüm kan zijn, iets met een blijvende waarde. Zijn zinsbouw kenmerkt zich door het opvallende en veelvuldige gebruik van dubbele punten op plekken waar normaliter een punt of komma geplaatst zou worden. Richting het eind van Francescho’s sectie komen we erachter dat de schilder deze specifieke interpunctie heeft overgenomen van zijn moeder, die – net als Carol – op jonge leeftijd overleed. Taal is in deze hoedanigheid een middel dat Francescho inzet om de herinnering aan zijn moeder levend te houden; via zijn woorden leeft zij door in zijn heden. Hiermee vormt literatuur zich wederom naar een mediumspecifieke kwaliteit van de schilderkunst, zoals beschreven door Francescho:

[P]ainting, Alberti says, is a kind of opposite to death . . . it’s many a person who can go to a painting and see someone in it as if that person is as alive as daylight though in reality that person has not lived or breathed for hundreds of years. (Smith 343)

De schilderkunst, zo blijkt, is in staat om leven te vangen in zijn stilstand. Vaststaand en voortdurend is het schilderij een baken om naar terug te keren en een poort naar een verleden tijd. Het medium heeft een conserverende functie en is hiermee geschikt om herinneringen te koesteren. Francescho’s adoptie van zijn moeders interpunctie laat zien dat ook taal een drager van herinneringen kan zijn. Tegelijkertijd reflecteert de conceptualisering van schilderkunst als “a kind of opposite to death” op het medium als iets levendigs, iets wat immer in beweging is. Hiermee spiegelt het schilderij zich op zijn beurt aan de taal, die volgens Carol gezien moet worden als “a growing changing organism” (9). Dat een enkele uitspraak te lezen is als zowel een reflectie via schilderkunst op wat literatuur kan doen als een reflectie via literatuur op wat schilderkunst kan doen, getuigt van het ontbreken van rigide grenzen en van de kruisbestuiving tussen media in een intermediaal speelveld.

Conclusie

How to Be Both barst van de filosofische overpeinzingen, verfrissende opvattingen en tegenstrijdige inzichten over schilderkunst, literatuur en de relatie tussen de twee. Het boek overstijgt grenzen van media en tijd en is hiermee een hommage aan de veelzijdigheid van kunst. In mijn onderzoek heb ik me gericht op intermediale referenties – zoals gedefinieerd door Irina Rajewsky – naar de schilderkunst van Francesco del Cossa als middel om de temporeel gebonden narratieve vorm van de roman te herzien. In eerste instantie heb ik vastgesteld dat schilderkunst, in tegenstelling tot literair narratief, in staat is een verhaal te vertellen in een enkel beeld. Een schilderij maakt tijd tijdloos en exposeert een oneindigheid aan verschillende visies tegelijkertijd. Vervolgens heb ik geprobeerd in kaart te brengen op welke manieren Smith deze mediumspecifieke simultaniteit vertaald heeft naar de romanvorm, om met het fresco als model een nieuwe manier van literair verhaal vertellen te verkennen. De nadruk lag hierbij op de zoektocht naar alternatieven voor temporele lineariteit, causaliteit en sequentialiteit; deze werden gevonden in onder meer de structuur van de wederkerige raamvertelling en de “present-time narration” in Georges narratief. Dit formele experiment met het fuseren van heden en verleden kan in verband gebracht worden met de verwerking van rouw, een van de thematische assen in de roman. Hoewel How to Be Both manieren suggereert waarop literatuur synchroniciteit kan verbeelden, blijft het boek zich ook bewust van de beperkingen van het medium. Door literaire grenzen zowel te verleggen als te herkennen, doet Ali Smith een voorstel van wat de roman via intermediale referenties van de schilderkunst kan leren. Waar George vreest dat de superimpose van verhaallijnen de tekst onleesbaar zal maken, bewijst Smith de potentie van simultaniteit van verschillende hedens en verledens in het boek als literair fresco.

Bibliografie

Gordon, Niamh. “Grief, Reading, and Narrative Time.” The Polyphony, 11 nov. 2021, thepolyphony.org/2021/11/11/grief-reading-and-narrative-time/.

Grabes, Herbert. “Sequentiality.” The Living Handbook of Narratology, 26 maart 2014, www-archiv.fdm.uni-hamburg.de/lhn/node/91.html.

Huber, Irmtraud, en Wolfgang Funk. “Reconstructing Depth: Authentic Fiction and Responsibility.” Metamodernism: Historicity, Affect and Depth After Postmodernism, red. Robin van den Akker et al., Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd, 2017, pp. 151-166.

Keyes, C. D. “Art and Temporality.” Research in Phenomenology, jrg. 1, 1971, pp. 63-73. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24654420.

Manca, Joseph. “Style, Clarity, and Artistic Production in a Courtly Center: Some Myths about Ferrarese Painting of the Quattrocento.” Artibus et Historiae, jrg. 22, nr. 43, 2001, pp. 55-63. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1483652.

McCartney, Mary E. “The Architecture of Narrative Reciprocity in Ali Smith’s How to Be Both.” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, jrg. 63, nr. 3, 2022, pp. 331-343. Taylor and Francis Online, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00111619.2022.2032572?casa_token=KNySeDiBFGcAAAAA:NdeKSbHuxVxHsKbTsf2f6iDElnwzOgxQXbc6k5TEEuly4p4k2lb xkCkFnrjsJenTGPsm4FlIxqELoA.

Rajewsky, Irina O. “Intermediality, Intertextuality, and Remediation: A Literary Perspective on Intermediality.” Intermediality: History and Theory of the Arts, Literature and Technologies, nr. 6, Centre de recherche sur l’intermédialité, 2005, pp. 43-64. Erudit, https://doi.org/10.7202/1005505ar.

Shigematsu, Eri. “Is It Narration or Experience? The Narrative Effects of Present-Tense Narration in Ali Smith’s How to Be Both.” Language and Literature, jrg. 31, nr. 2, Sage, 2022, pp. 227-242. Sage Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/09639470221090865.

Smith, Ali. “Ali Smith: ‘He looked like the finest man who ever lived’.” The Guardian, 24 aug. 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/aug/24/ali-smith-the-finest-man-who-ever-lived-palazzo-schifanoia-how-to-be-both.

—. How to Be Both. Penguin Books, 2014.