Rosalie Blom schreef dit artikel op basis van haar scriptie voor de bacheloropleiding Algemene Cultuurwetenschappen.

In hoeverre verschaft poëzie ons inzicht in de complexiteit van de wereld waarin we leven? “The writer has chosen to reveal the world,” zo stelt filosoof Jean-Paul Sartre over de intentie van de schrijver; “and particularly to reveal man to other men so that the latter may assume full responsibility before the subject which has been thus laid bare”. Wat hij daarmee zegt is: ongeacht of literatuur instemt met de heersende status quo; zij getuigt wel degelijk van haar aanwezigheid. En niet alleen dat: literatuur legt een bepaalde verantwoordelijkheid bij haar lezer. Wanneer poëzie bepaalde maatschappelijke vraagstukken blootlegt, in hoeverre vallen deze dan nog te negeren?

Het gedicht “aantoonbaar geleverde inspanning,” afkomstig uit de bundel Habitus (2018) van Radna Fabias, is zo’n voorbeeld van een onvermijdelijk politiek werk: de titel van het gedicht refereert aan een formulier waarmee inburgeraars om ontheffing van het inburgeringsexamen kunnen vragen. Het inburgeringsexamen, de proeve die je moet afleggen om tot Nederland te worden toegelaten, is grofweg een door de Nederlandse overheid opgestelde, ‘scheve deal’: complete culturele loyaliteit in ruil voor burgerschap. De aanvraag “ontheffing wegens aantoonbaar geleverde inspanning” komt in beeld wanneer deze culturele loyaliteit niet duidelijk genoeg blijkt uit dit inburgeringsexamen. “U moet bewijzen dat u het wel hebt geprobeerd”, aldus het formulier (Minder of geen examens: Genoeg cursus en examens gedaan – DUO Inburgeren).

Koloniale patronen

De interactie tussen de immigrant en de Nederlandse overheid vertoont een complex spanningsveld: niet alleen wordt de immigrant geacht kennis te vergaren over de Nederlandse taal en samenleving, maar vooral ook wordt de overname van Nederlandse culturele waarden hier centraal gesteld. Deze beleidsbenadering vertoont parallellen met het koloniale verleden, waarbij de manier van oplegging van bepaalde westerse doctrines vergelijkbaar is met de methoden die kolonisatoren in dit tijdperk hanteerden. Welbeschouwd valt deze oplegging te herkennen als mimicry; een postkoloniaal concept ontwikkeld door literatuurwetenschapper Homi Bhabha. Mimicry is, kortweg, het onvolledig nabootsen van de kolonisator door het gekoloniseerde subject en fungeert binnen postkoloniale literatuur als middel tot verzet tegen de kolonisator wanneer deze imitatie een satirisch karakter heeft.

Vanuit dit kijkvenster kan Fabias’ gedicht “aantoonbaar geleverde inspanning” gelezen worden als nabootsing van het daadwerkelijke formulier van “ontheffing wegens aantoonbaar geleverde inspanningen” – naast de titel, komt namelijk ook de inhoud van het gedicht overeen met de inhoud van het formulier.

Het Nederlandse culturele archief

De maatschappelijke context van Fabias’ gedicht is de Nederlandse samenleving; en dan specifiek de delen van de samenleving waarmee een inburgeraar in aanraking komt. In het boek Witte onschuld: paradoxen van kolonialisme en ras geeft antropoloog Gloria Wekker invulling aan het culturele archief van Nederland, een term eerder gedefinieerd door literatuurwetenschapper Edward Said om naam te geven aan de opslagplaats van normen en waarden die een bepaalde cultuur tekent.

Said stelde vast dat er in het West-Europese discours sprake is van een westerse Zelf en een oosterse Ander, waarbij het beeld van de Ander (‘de Oriënt’) een westerse constructie is die, in plaats van iets concreets over het oosten te zeggen, vooral iets zegt over westerse machtsuitoefening (Pattynama 158).1 Het westerse Zelf in Nederland is volgens Wekker getroebleerd: er is sprake van een centrale paradox. Nederlanders zien zichzelf als neutraal, tolerant en niet-racistisch, maar ondanks dit zelfbeeld is er in Nederland sprake van witte superioriteit (“white supremacy” (hooks 63)), met als gevolg dat mensen die afwijken van deze witte norm als anders (‘de Ander’) gezien worden.

Gekleurde mensen zullen altijd nog allochtonen blijven, de officiële en zogenaamd onschuldige term voor ‘degenen die van elders kwamen’, waardoor gekleurde mensen eindeloze generaties [lang] worden geracialiseerd en nooit tot het Nederlandse volk zullen gaan behoren. De tegenhanger van ‘allochtonen’ is autochtonen, ‘degenen die van hier zijn’, wat – zoals iedereen weet – slaat op witte mensen. (Wekker 28)

Het culturele archief – de binaire oppositie tussen, in Wekkers woorden, ‘degenen die van hier zijn’ en ‘degenen die van elders komen’ – sijpelt door in hedendaagse structuren, maar blijft verborgen onder het idee van tolerantie. De houding van ‘de westerse Zelf’, of dat nou systemen of individuen zijn, jegens de niet-westerse (lees: niet-witte) Ander, is dus vrij ambigu.

Een tegenstrijdig welkom

Deze ambiguïteit is in het gedicht “aantoonbaar geleverde inspanning” haarfijn in beeld gebracht. Zo luidt de verteller, haar stem een imitatie van de stem van de Nederlandse beleidsvoerders: “we heten de ballotant welkom”; echter spreekt het voornaamste deel van het gedicht dit warme welkom tegen. Op opsommende wijze is er een lijst van alle sociaal-culturele Nederlandse normen, waarden en kenmerken opgesteld waarover een immigrant, hier een Zwarte vrouw uit Curaçao, zou moeten beschikken om tot de Nederlandse samenleving toegelaten te worden. Het gedicht is geformuleerd in de onvoltooid tegenwoordige tijd met de immigrant (“de ballotant”) als taalkundig onderwerp van de zinnen. Deze keuze transformeert de opeenvolging van beschrijvingen tot een richtlijn van een bevelende aard, maar dan gepresenteerd als een beschrijvende vertelling.

Om het gedicht “aantoonbaar geleverde inspanning” vanuit een ‘mimicriaanse’ blik te lezen, is het essentieel dat mimicry in haar volledigheid begrepen wordt. Hoewel de term binnen de postkoloniale context gezien wordt als een strategie om koloniale machtsstructuren te ondermijnen, vindt mimicry haar oorsprong in de dynamiek van koloniale overheersing. Mimicry doelt op de wisselwerking tussen ‘de imitatie’ en ‘het origineel’: het draait om “een spanning tussen de hoogstaande idealen van de kolonisators om de gekoloniseerde gebieden ‘te verlichten’ en hun verlangen deze gebieden ‘dom’ en ‘onderworpen’ te houden” (Wurth en Rigney 386-387). Binnen dit koloniale discours is het doel dat het gekoloniseerde subject verlicht en ‘hetzelfde’ als de kolonisator wordt, zij het niet volledig; het streven blijft om het ondergeschikt te houden.

Het gedicht werpt licht op de manieren waarop deze vermeende ‘verlichting’ nog steeds een rol speelt in het hedendaagse immigratiebeleid. Zo wordt van de immigrant verwacht dat zij haar afrokapsel aanpast naar een “gepast kapsel” en dat zij haar moedertaal verruilt voor de “taal van de voormalig eigenaar”. Ze “gebruikt de heupen minder bij het dansen” en “beheerst de woede”, waarmee wordt verwezen naar westerse stereotypen over emotionaliteit en seksualiteit van Zwarte vrouwen (“Black, that is to say African Diasporic, women are generally seen as “too liberated,” with a rampant sexuality”, zo stelt Wekker in haar artikel “Diving into the Wreck: Exploring Intersections of Sexuality, ‘Race,’ Gender, and Class in the Dutch Cultural Archive” (161)).

Met zinsneden als “verbergt haar brandmerken” wordt niet alleen verwezen naar de periode van slavernij, maar ook naar de manier waarop dit verleden in de Nederlandse samenleving vaak verzwegen wordt, wat een van de vele praktijken is die herkenbaar is uit het culturele archief. Deze verwijzingen illustreren de voortdurende invloed van koloniale denkbeelden en praktijken op hedendaagse maatschappelijke structuren en attitudes, die de assimilatie van de immigrant nog steeds bepalen en haar dwingen om haar eigen identiteit en geschiedenis te verloochenen.

De imitatie van de immigrant blijkt op beperkte wijze mogelijk, aangezien veel natuurlijke kenmerken zoals haar en huidskleur niet zomaar kunnen worden veranderd – de immigrant blijft, in de woorden van Bhabha, “almost the same, but not white” (89). De mimicry, zoals deze hier op klassieke koloniale wijze voordoet, toont dat de Nederlandse overheid streeft naar het behoud van volledige controle en macht. De immigrant moet aan de Nederlandse witte normen voldoen, waarvan de onmogelijkheid van die eis resulteert in een hiërarchie op basis van (ras en) kleur.

De kracht van mimicry

Wat is, naast deze verwijzingen, dan de concrete wijze waarop het gedicht een illustratie is van mimicry als verzetsmiddel? Mimicry maakt gebruik van de cultuur van de koloniserende partij als een lens waardoor naar de kolonisator wordt gekeken. De kern van dit postkoloniale gebruik van mimicry is dat het initiatief van de imitatie ligt bij de (voormalig) gekoloniseerde. In plaats van passief het proces van gedwongen ‘verlichting’ te ondergaan en daarbij inherent inferioriteit te ervaren, is de gekoloniseerde zich actief bewust van de noodzaak tot imitatie en gebruikt zij het verschil dat haar inferieur zou maken als een middel om macht te verwerven.

Om succesvol te zijn, dient mimicry constant haar uitschieter, “its slippage, its excess”, zoals Bhabha deze noemt (86), te produceren. Op die manier wordt namelijk duidelijk hoe de gekoloniseerde bewust de onvolledigheid van de imitatie nastreeft. Een voorbeeld hiervan in “aantoonbaar geleverde inspanning” is de manier waarop het interieur van de woning van de immigrant beschreven is. Deze is aangepast op wat ogenschijnlijk gebruikelijk is in de Nederlandse samenleving – zo heeft de immigrant sierkussens en een schoorsteenmantel.

uit de eclectische doch coherente inrichting van het eigen huis spreekt beheersing wellicht zelfs synthese:

de tropische warmwatervissen hebben in zwart-witfoto’s een plek gevonden boven de schoorsteenmantel

de volgroeide, intelligent geplaatste cactus botst modieus met de caribisch blauwe accentmuur

de eerder bedwongen kleuren zijn nu accenten in de vorm van sierkussens, dekens en achteloos over meubelstukken gedrapeerde houten rozenkransen

[…]

belangrijke details: de bank is niet in plastic gewikkeld en de ballotant bezit opmerkelijk veel palmbomen

(Fabias 104)

Het interieur lijkt een poging te zijn van het aanpassen aan de Nederlandse samenleving, maar de eigen identiteit en het achtergelaten thuisland komen op vele manieren terug. Ook zijn er de zwart-wit foto’s van tropische vissen, evenals “de modieus geplaatste cactus” (104) en de Caribisch blauwe muur. De verloren zon keert terug in de kleur van onder andere de bank en een bloempot. De strofe “belangrijke details: de bank is niet in plastic gewikkeld en / de ballotant bezit opmerkelijk veel palmbomen” (104) symboliseert tegenstrijdigheid. De bank die niet langer in plastic is gewikkeld, schetst een beeld van permanentie en stabiliteit en suggereert dat de immigrant zich gevestigd voelt. De opmerkelijke hoeveelheid palmbomen suggereert daarentegen een verlangen naar het thuisland.

De klassieke mimicry is hier te herkennen in de wijze waarop het interieur verwesterd dient te worden en tegelijkertijd is deze passage een illustratie van het gedicht als mimicry in geheel. De uitschieter is hier helder aanwezig: de imitatie wijkt hier namelijk sterk af van hoe een daadwerkelijke lijst aan assimilatiecriteria eruit zou zien. De nadruk ligt op een tegenstrijdigheid en belicht hier in plaats van een extreme loyaliteit aan de Nederlandse cultuur (zoals bijvoorbeeld het “is bereid te leren fietsen met een paraplu in de hand” (105), later in het gedicht) ook een loyaliteit aan de eigen cultuur. Deze uitschieter is een bewust teken van verzet; wat laat zien hoe de immigrant dan wel het Nederlandse interieur kan imiteren, maar dat dit niet betekent dat ze binnen die imitatie geen ruimte heeft voor verzet.

Kortom

De essentie van mimicry ligt niet in louter het reproduceren van de dominante Nederlandse cultuur, maar veeleer in een complexe vorm van nabootsing waarbij de gekoloniseerde individuen aspecten van de overheersende cultuur overnemen, terwijl zij gelijktijdig een zekere mate van controle en aanpassing behouden. “Mimicry conceals no presence or identity behind its mask”, aldus Bhabha. “The menace of mimicry is its double vision which in disclosing the ambivalence of colonial discourse also disrupts its authority” (88). In andere woorden: de kern van mimicry als postkoloniale tactiek is dat de immigrant, in plaats van passief, actief is in haar imiteren. Simpelweg met haar ‘ambivalente bestaan’ ontwricht zij de machtsstructuur.

Mimicry, dat traditioneel gebruikt wordt om te onderdrukken, wordt hier als methode toegeëigend: de onderdrukking wordt tegengegaan middels een satirische imitatie van die onderdrukking. Hierdoor wordt Nederland, het beleid maar ook de samenleving, geconfronteerd met de manier waarop zij macht uitoefenen; een manier die het zelfbeeld van gelijkheid en tolerantie tegenspreekt. Een grondige (maar zelfs al een basale) analyse brengt aan het licht wat de vertelinstantie beoogt te communiceren: de verwijzingen naar voortlevende koloniale hiërarchie, racisme, en zelfs seksisme zijn lastig te omzeilen. Zoals Wekker benadrukt: de Nederlandse samenleving is vaak geneigd tot stilzwijgen, met het koloniale tijdperk dat als verleden wordt beschouwd en witte Nederlanders die zichzelf als kleurenblind en tolerant beschouwen. In deze traditie zou het dan ook passend zijn om de bundel van Fabias in zijn geheel links te laten liggen. Als er geen erkenning is van koloniale verhoudingen, hoe kunnen deze dan effectief worden ondermijnd en uitgedaagd?

Fabias heeft, door te steunen op een officieel beleidsdocument, de mogelijkheid uitgesloten dat haar gedicht beschuldigd kan worden van aanspraak maken op iets fictiefs. De brede waardering van Habitus heeft ervoor gezorgd dat de faam van de bundel zich ver buiten de Nederlandse literaire kringen heeft verspreid. Door middel van een kritische blik op de ervaringen van immigranten in de Nederlandse samenleving voegt de bundel zich bij andere literaire werken en sociale commentaren die de complexiteit van immigratie, culturele assimilatie en de impact van overheidsbeleid belichten. Mogelijk draagt Habitus, en met name het gedicht “aantoonbaar geleverde inspanning”, bij aan het grotere gesprek over integratie en koloniale machtsstructuren binnen de Nederlandse context.

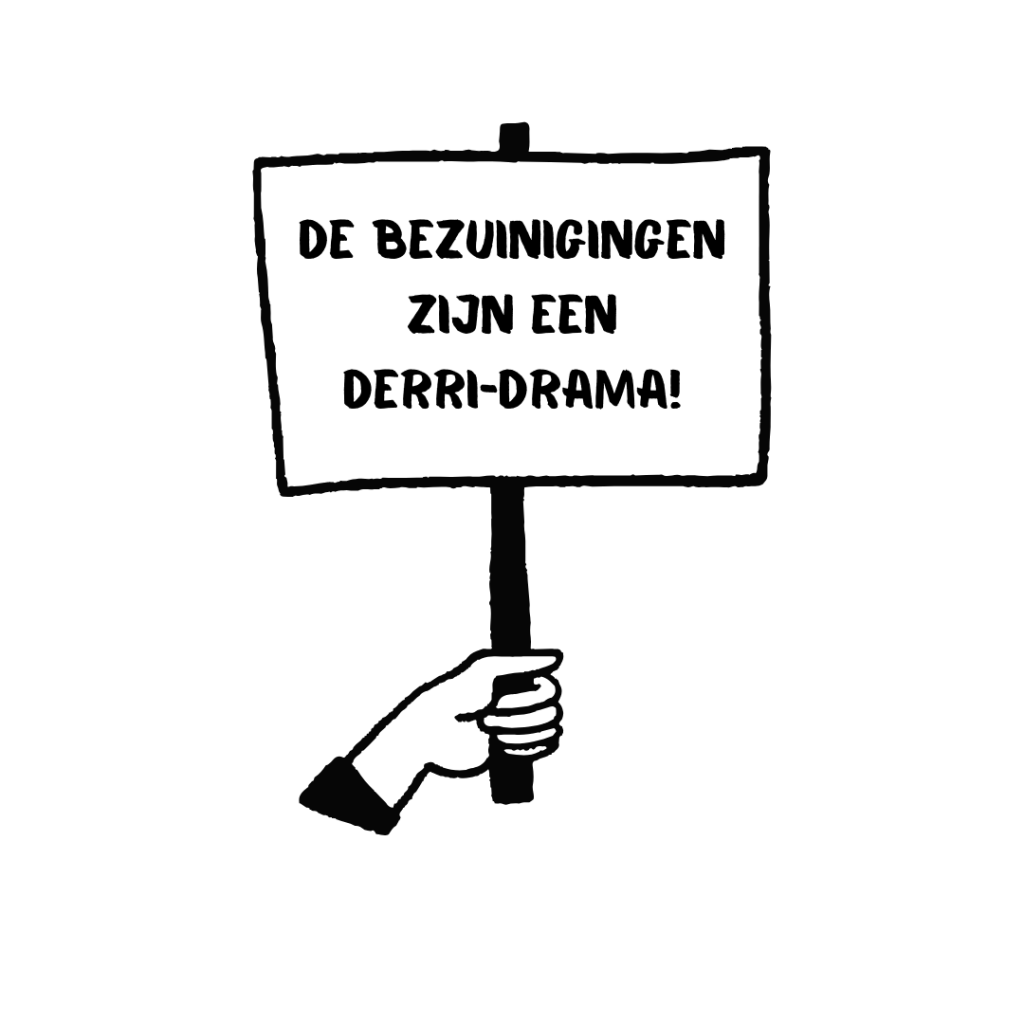

De illustratie bovenaan dit artikel heet “opmerkelijk veel palmbomen” en is gemaakt door Rosalie Blom (2024).

Bibliografie

Bhabha, Homi Κ. “Of mimicry and man: the ambivalence of postcolonial discourse”. The location of culture, 1994, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA22500601.

Essed, Philomena. Alledaags racisme. Feministische uitgeverij Sara, 1984.

Fabias, Radna. “aantoonbaar geleverde inspanning”. Habitus, De Arbeiderspers, 2018.

hooks, bell. “Talking back: thinking feminist, thinking Black”. Feminist Review, nr. 33, januari 1989.

ILFU. “Radna Fabias – 1000 dichters – De Nacht van de poëzie on Tour – 26-09-2023”. YouTube, 26 september 2023, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=okjoi61U7m0.

“Minder of geen examens: genoeg cursus en examens gedaan – DUO inburgeren”. inburgeren.nl, http://www.inburgeren.nl/minder-of-geen-examens/genoeg-uren-cursus-gedaan.jsp.

Ministerie van Algemene Zaken. “Immigratiebeleid Nederland”. Rijksoverheid.nl, 14 maart 2023, http://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/immigratie-naar-nederland/immigratiebeleid-nederland.

Odijk, Janice. Natural Hair Bias Against Black Minorities: A Critical Investigation of Intersecting Identities. Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, 2020, Masterscriptie.

Pattynama, Pamela. “Het dubbele bewustzijn van de vreemdelinge.” Vrouwenstudies in de cultuurwetenschappen, edited by Rosemarie Buikema en Anneke Smelik. 1993, pp. 157-169.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. “What Is Literature?” and Other Essays. Harvard University Press, 1988.

Swanborn, Peter. “Grote Poëzieprijs 2019 naar Radna Fabias, debutant ‘slaat brug tussen geest en het eenzame vleselijke lichaam’”. De Volkskrant, 16 juni 2019.

Wekker, Gloria. Witte onschuld: Paradoxen van kolonialisme en ras. Amsterdam UP, 2017.

Wekker, Gloria. “Diving into the Wreck: exploring intersections of sexuality, ‘Race,’ gender, and class in the Dutch Cultural Archive”. BRILL eBooks, 2014, pp. 157–78. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789401210096_009.

Wurth, Kiene Brillenburg, en Ann Rigney. Het leven van teksten: een inleiding tot de literatuurwetenschap. Amsterdam UP, 2008.