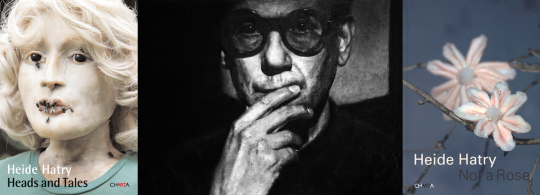

For nearly

a decade, German-born New York-based neo-conceptual artist Heide Hatry has

laboured in great secrecy on her new project. Following Heads and Tales (2009), a series of sculptural

busts of women produced using untreated pig skin, flesh, and body parts, and Not a Rose (2012), a book reflecting on the

cultural meaning of flowers that revolves around her photographs of flower-like

sculptures made from the offal, sex organs, and other parts of animals, Icons in Ash: Cremation Portraits is the next step in Hatry’s bio-art

which may also be her breakthrough with a larger public. Icons in Ash is a series of portraits of deceased people made with

their own ashes. Blurring the boundaries between presence and absence, being

and representation, matter and nothingness, it invites reflection on

memorialisation and commemoration practices, on the meaning of life and death, on

the extent to which and ways in which death is present or not in life, and on

such practical matters as what to do with cremains, the dead’s remains left from

cremation. Scatter them over the sea? Keep them in an urn on the mantelpiece?

Turn them into art?

Like all

bio-art, Icons in Ash is not

uncontroversial. Its conversations with the dead – both the ones in which the

artist engages and the ones the viewer carries out with the portrait – are

transgressive, and not only in the sense of crossing the boundary between life

and death, the living and the dead. With her cinerary art, Hatry also hovers

about the threshold between art and the funerary market, which includes urns,

jewellery, and memorials, all designed to commemorate deceased loved ones by

holding remains, ashes, or keepsakes. Crucial to Icons in Ash, however, is the process of becoming-portrait, the

painstaking artistic process of making that literalizes re-membering by

performing it. Icons in Ash ‘does’

memory as a (re)constructive gesture. Taking time, the making of the portrait

is a ritual of transformation of matter. This transfiguration of remains into

portrait is an ingenious way of keeping the memories of deceased loved ones

alive. At once representing (in the sense of mimesis) and re-presenting (in the

sense of making present again), the portraits are memorials for loved ones that

take the ashes out of the cremation urn to reconstitute their likeness with

their remains. As the portrait becomes both the container (urn) and the

contained (ashes) – and in fact container and contained are even further

blurred as Hatry mixes the human ashes with white marble dust (reminiscent of

funerary urns, graves, and stelae) and black birch coal (evocative of the

wooden coffin) – absence is transformed into a material presence in which self

and representation coincide and become one. As such, Icons in Ash also restores the image to its original purpose: to

keep the dead among the living. Whereas the veneration of the dead,

specifically ancestors, is rather marginalized in dominant cultures of the

Global North, Hatry’s art facilitates the presence of death in life, enabling

the dead to grace their survivors with their presence.

So, how

does Hatry do this? As she explains in an interview, because the ashes are pure bones

and therefore monochrome, she uses white marble dust (which doubles as a symbol

of death) and black birch coal (functioning as a symbol of life) to get a

palette ranging over different shades of grey. To make the portraits, she

developed three different techniques, which also differ in how time-consuming

they are for the artist (and hence, how expensive they are for the purchaser). First,

there is the mosaic technique, applying loose ash particles with the tip of a

scalpel on beeswax. This is the most time-consuming method, taking weeks to meticulously

piece together the portrait out of the ashes. Second, there is the method of drawing layers of very diluted ink

onto either an emulsion of ashes and binder, or on a surface of pure

ashes. Finally, and much cheaper than the first two methods, Hatry

developed a photographic technique in which she recreates a photograph on

either a surface of pure ashes or on a surface bearing an emulsion of ashes and

binder. This latter technique especially was developed with the prospective

client in mind; because many people who might be interested in having such a

portrait can’t afford the mosaic-image that is so time-consuming to create. Developing

various techniques of cinerary portraiture, Hatry’s has created a bio-art that

extends our lives in art, enabling humans (and animals: she also does portraits

of pets) to be present in their likeliness.

Websites:

– http://iconsinash.com/

– www.heidehatry.com/

Photo: Heide

Hatry, Roberto Guerra (2016). © Heide

Hatry. Reproduced with the artist’s permission.