By Reza Zefanya Mulia

A. Museum Storyteller: Now

In the current cultural context, storytelling about a museum’s collections or ongoing exhibitions goes beyond simply providing object details such as title, materials, date of origin, and historical descriptions. For social media posts, storytelling is also not merely a supplement to fulfil the institution’s marketing strategy. Rather, it has become an extension, and arguably a central aspect, of the museum’s mission to share knowledge with the public. Writing stories — whether for object labels within a gallery or digital content for a museum’s social media — no longer rests solely with the curator. As museums’ educational objectives evolve, the narratives accompanying objects extend beyond wall text and labels to include digitised formats for distribution across digital platforms such as social media, video streaming services, websites, and newsletters.

With this new objective, museums come up with new professional role in order to develop their narrative matters: the storyteller — a position that could be under curatorial and interpretation or education and learning department. Museums possess a unique opportunity to establish trusted spaces, both physical and digital, for shared learning and development. Through the creation of dynamic spaces and the use of personalised storytelling strategies, museums can cultivate the same level of audience trust online as they achieve in their physical spaces. Timothy (2011) wrote that by enlivening the past and enabling personal resonance, visitors can establish a deeper connection with the sites they explore.

A fundamental goal of interpretive programmes should be to provoke active engagement, encouraging visitors to participate in conservation, education, volunteering, or fostering an enduring appreciation for heritage across future generations. The interpretation of objects and the narrative framework used to present them to audiences are central to the storyteller’s role. The primary objective of interpretation is not merely to instruct or convey facts, but rather to stimulate constructive action among visitors. Effective narrative should inspire by offering new insights, rather than solely factual content.

Storytellers must recognise the diversity of individual experiences, ensuring that the interpretive process fosters meaningful engagement by revealing knowledge beyond basic data associated with objects. This paper will examine the challenges faced by museum storytellers in navigating current technological advancements, while exploring practical examples that highlight the application of new writing approaches to enhance storytelling engagement.

B. Navigating AI in Museum Storytelling: Challenges, Strategies, and the Importance of Human-Centred Narratives

With the rapid advancement of online channels and content development tools, storytellers within cultural institutions face a challenge similar to copywriters in the broader creative industry: the potential of being replaced by artificial intelligence in terms of content production. Since late 2022, media coverage and public discussions on AI have surged, with generative AI, particularly ChatGPT, at the forefront. AI has not only become a trending topic, but expectations regarding its future potential have significantly heightened.

From this, some have argued that generative AI will replace certain jobs, while others have highlighted that it could enhance work in various professions and even create new roles. The transformative potential and risks of artificial intelligence have dominated public debate across many countries in recent years, sparking a range of visions, expectations, and uncertainties. A considerable part of this exaggerated discourse has centred on the possible effects of generative AI on labour markets, covering a wide spectrum of occupations, including those involved in text production, such as copywriters (Vicsek et al., 2024).

This discourse opens up to more focused conversation related to the role of creative industry practitioners in a museum environment, especially their content writer who might be at threat of job replacement due to AI growth. Though different in tone of voice and writing approach, storytelling in museums could be rooted in the same spectrum of copywriting in marketing. Both are involved in developing a strategy for the writing that encourages people (or museum visitors) to take action, using a creative combination that aids in delivering the message effectively (Hernández, 2017).

Furthermore, Hernández wrote that crafting a message through copy involves establishing a tone of how the writers want their message to resonate in the minds of their audience. There are specific structures in writing copy and storytelling that create a framework for how these pieces will engage the public — to prompt a response in the form of thoughts, words, or actions. The storytelling component in museums originates from and is directed towards interpretation: the storyteller observes an object and composes a narrative based on their interpretation, which is subsequently presented to the audience in order to stimulate their own interpretive response.

Public’s interpretation, on the other hand, needs more effort in order to take shape as a knowledge. Knowledge acquisition through interpretation requires understanding in the visitor’s backgrounds, one’s own bias, and contexts (Langer, 2022). Nevertheless, the knowledge distribution through storytelling is unique and cannot be using a one-size-fits-all approach. Whilst there are recommended structures in writing, to know who we speak to in terms of understanding our audiences through in-depth research is still an important aspect before starting to write a copy.

In a study exploring the anticipated replacement of creative writing by AI and its potential consequences, Vicsek, Pinter, and Bauer (2024) conducted research seeking insights from creative writers. This investigation employed the framework of the sociology of (technological) expectations, which highlights the crucial role of anticipatory beliefs in shaping technological developments within modern capitalist societies, as outlined by Borup et al. (2006).

This research builds upon previous studies by Beckett (2019), Ellekrog (2022), and Mackova and Marik (2023), which indicate that creative writers, including journalists, believe that AI will not replace their creative outputs, as the process still requires human creativity to imbue the work with a “human touch.” On the contrary, a survey by Breen (2020) revealed that 23% of US marketing experts believed AI could replace copywriting. Rajan, Venkatesan, and Lecinski (2019) come with an optimistic state that throughout their research, they find the actors in the marketing sector (i.e., creative workers) acknowledged that AI is transforming the field by enhancing analytics, personalising messages, improving campaign efficiency, and boosting productivity.

Furthermore, the creative boost that AI may offer includes increased efficiency in tasks such as automatically transcribing oral interviews and speeding up the retrieval of background information. Hence, the usage of AI will be more likely to become only tools in speeding up the work process, rather than a complete dismissal of a writer’s job in building a narrative. An example can be drawn from the role of copywriters, who rely on their own observations and experiences to engage in an imagined dialogue with an internalised audience, the “implied reader” of advertising texts (Kover, 1995).

A writer’s unique social background will also shape how they construct their narrative. McLeod, O’Donohoe, and Townley (2009) argued that diversity in social backgrounds may become increasingly significant in sustaining this productive tension. In addition to interacting with imagined others, writers also engage in dialogue with their work partners. The generation of creative ideas involves both partners in a dynamic exchange as they work together to craft messages that connect products with members of a target market (Hackley and Kover in McLeod et al., 2009).

Most specifically, museum storytellers — whose role extends beyond merely writing stories — could benefit from AI to streamline their workload. Although the storytellers still need to conduct research, examine real objects to develop narratives through field inspections (for example, looking at sculptures and their textures could trigger sensory experience that inspire writers to write their story), and engage with relevant individuals for the essential “human touch,” AI could assist with time-consuming tasks such as proofreading for typographical errors, transcribing interviews, or finding alternatives for condensing paragraphs to meet object label word limits.

The discourse on how a museum’s narrative through object labels or curatorial notes should be presented has been started with an argument that a didactic approach shall not be present anymore. In the age of meaning-making, a human touch is essential in the 21st century museum visit experience. In his article “The Why, What, And How Of The Best Storytelling In Museum Exhibitions”, Filene (2022) emphasised that museums must find ways to connect with visitors by relating to their experiences. Personal connection is crucial for successful museum learning, and emotional engagement — an integral part of effective storytelling — is not a distraction but a powerful tool for fostering exploration and meaning-making. As previously mentioned through an example of object observation in a way of building a solid writing, this act of human touch could trigger emotional engagement and empathy — something that has yet to be replaced by the presence of AI.

C. New Approach: Learning How The Burrell Collection Tells Their Story

The Burrell Collection is part of Glasgow Life Museums, located in the southside part of Glasgow. The museum hosts 9.000 objects, including collections of Chinese art, mediaeval treasures such as stained glass, arms and armour, tapestries, and paintings by renowned French artists such as Manet, Cézanne, and Degas. They reopened on 29 March 2022 following a major six-year refurbishment and redisplay. One of the most highly praised aspects of the renovation is the introduction of new interactive and immersive experiences for visitors of all ages. This transformation contributed to the museum winning the prestigious Art Fund Museum of the Year award in 2023.

The technological aspects that The Burrell Collection use to present their collections are just tools and methods — one important element that binds them all is the storytelling. In her report for The Art Newspaper, Joanna Moorhead (2023) noted that the museum’s approach on their object label for Mary Magdalene limestone sculpture wasn’t about Renaissance craftworks nor about the history of the object. Instead, it asks “How do you think she’s feeling?”

The Burrell Collection’s object labels have been reinterpreted for all-comers — from regular tourists, local visitors, academics, historians, and many others. They believe that a story that is generally relatable to the mass public will make it easier for them to connect with the objects. Hence, a prior knowledge of art history or specialised training in some subject matters are not necessary for one to read and understand the labels, as Moorhead mentioned.

Figure 1: The Burrell Collection staff member working with the local community to write a narrative regarding the future object label. Photo courtesy of The Burrell Collection.

Before developing their storytelling approach, The Burrell Collection conducted interviews, focus groups, surveys, workshops, and design testing involving local communities to ensure the displays reflected stories relevant to both new and returning visitors. This collaborative process provided local residents with the opportunity to express what matters to them and see it represented within the museum. This collaboration has significantly shaped the design of the displays, the stories featured, and the tone in which they are told. For instance, the curators collaborated with the local Iranian community to develop interpretations of objects from Persia and with the LGBTQ+ community regarding the porcelain figure of Guanyin. Visitor feedback has been overwhelmingly positive, with 97% of those surveyed indicating that it was a good experience.

This new approach, while highly experimental and innovative, has faced criticism, particularly from historians who accuse the museum of undermining the essential historical narratives of certain objects. They argue that the museum has adopted “wokism” (or a state of being woke, associated with behaviours in social justice discourse) within its institution. One critic, a follower of Buddhism, expressed offence at the portrayal of Guanyin as a trans figure.

As Langer (2022) noted in her book, the most effective stories are those that are highly specific — focused on particular individuals, and grounded in a distinct time and place. A simple yet compelling illustration of the power of specificity can be seen in an exhibition on Sami culture, as discussed in one of the chapters. This exhibition presents the personal narratives of two Sami individuals, interviewed at three distinct stages of their lives, offering a more intimate perspective, rather than relying on generalised portrayals of indigenous traditions and broad claims about the resilience of their culture.

Langer also added that when we incorporate experimentation into our storytelling approach with a commitment to listening and responding to how our audiences engage with our efforts, “storytelling” can evolve beyond a postmodern metaphor. It can serve as a guiding principle in our endeavour to make museums the relevant, transformative gathering spaces. While The Burrell Collection cannot meet the expectations of all visitors, and many perspectives exist on which narrative best represents the exhibited objects, their efforts to engage visitors with themes relevant to people’s daily lives deserve appreciation in opening up this experimental and cutting edge approach in storytelling.

D. Diversifying Stories Through Digital Channels

With the increasing shift towards distance learning and digital storytelling, a trend that has intensified since the COVID-19 pandemic, it is more crucial than ever for museums to dedicate significant time and resources to enhancing their digital presence (Carlisle, 2022) as Akker’s opinion (2016) on the state of digital technology that should serve to enhance and expand the museum experience and its functions, rather than replacing them with an alternative. John Stack, former Digital Director of Tate, noted that new technologies and online services, alongside the widespread availability of high-speed internet and mobile connectivity, have significantly transformed the web in recent years (Stevens, 2016). However, how do these technological advancements enable museums to better serve their audiences? This same question was raised by Bautista (2014), who critiqued the reliance on technology in museums, questioning its effectiveness in fostering meaningful engagement with their communities.

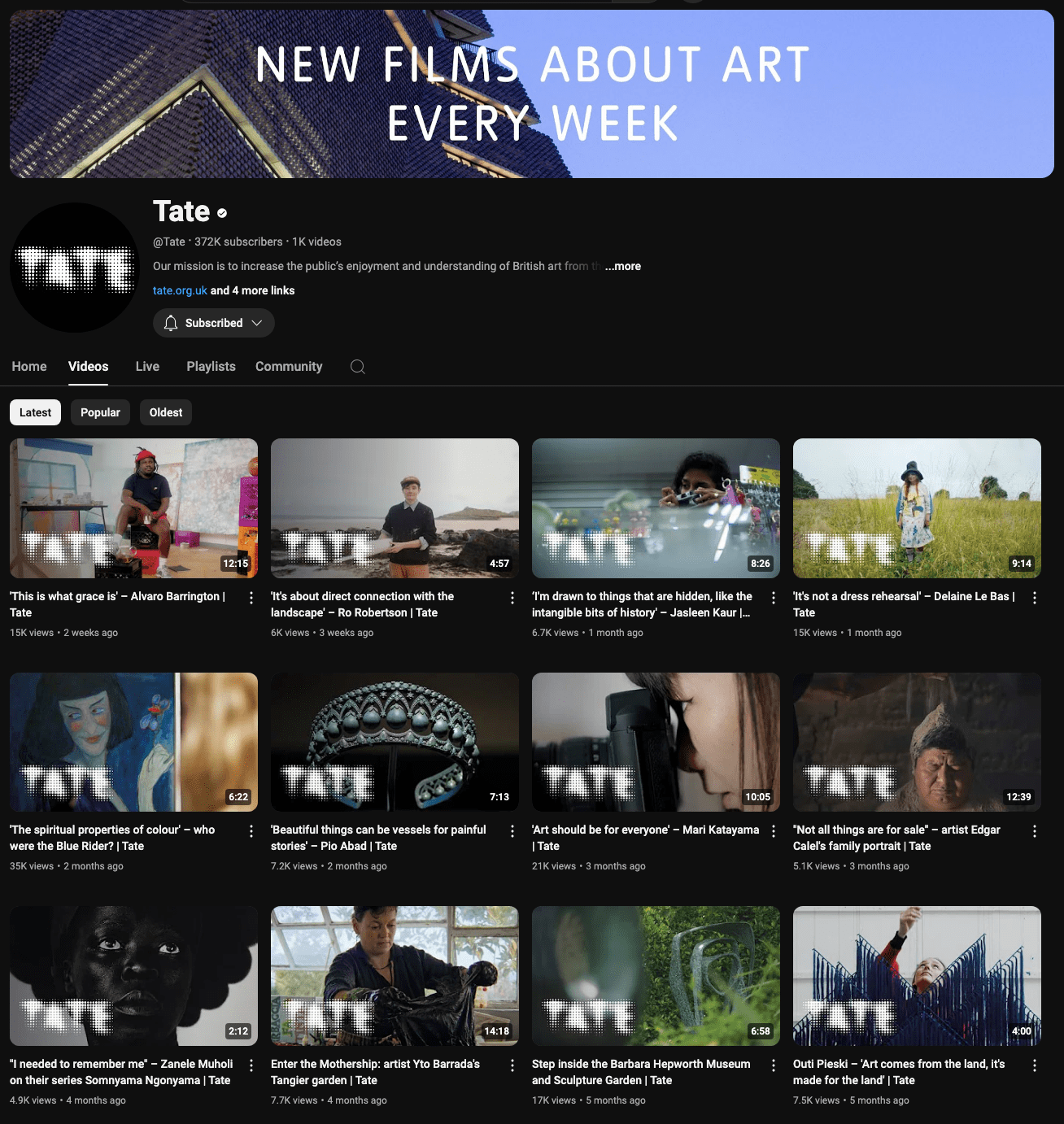

One museum that has successfully created engaging storytelling content through its digital presence is Tate (Britain, Modern, Liverpool, St. Ives) in the United Kingdom. Tate utilises a range of social media platforms, each with distinct strategies, tones of voice, and narratives, aligning with Akker and Legêne’s (2016) argument that museums should employ different narrative models for their on-site and online engagements. Furthermore, Carlisle (2022) wrote that by creating dynamic digital spaces and implementing one-to-one storytelling strategies, museums can successfully foster the same audience trust online as they do in their physical spaces.

Figure 2: Tate’s YouTube Channel — branding itself to be up-to-date every week with new films about art. Signalling the productive efforts in launching the video-based story.

While each of Tate’s physical museum spaces focuses on displaying world-class artworks within pristine white walls, its digital marketing team employs digital storytelling by tailoring each platform to its unique narrative. For instance, their YouTube channel centres on in-depth interviews with artists and curators, alongside tutorials inspired by other artworks—all professionally produced with scripts, camera work, and high production values. In contrast, their Instagram Reels feature more spontaneous, phone-recorded content, such as inviting visitors to share their thoughts on particular exhibitions.

While storytelling naturally fits longer, more structured videos like those on Tate’s YouTube channel, how does it function in shorter, more candid formats, such as on Instagram? By creating dynamic digital spaces and adopting one-to-one storytelling approaches, museums can establish audience trust online, mirroring the trust cultivated in their physical spaces (Carlisle, 2022). Visitor responses about their exhibition experiences may seem like simple testimonials, yet these responses are storytelling in their own right.

Figure 3: One of Tate’s Reels videos. Highlighting on a visitor’s thoughts from their visit.

The most impactful stories forge connections: exhibition stories can encourage personal reflection and connection — among family members and occasionally among strangers. Story-sharing often becomes part of the exhibition experience itself (Langer, 2022). This storytelling emerges after visitors have engaged with the narratives conveyed through object labels on the museum’s walls, embodying a personal perspective that can be shared with future visitors or accessed by learners via mobile devices. In the age of internet and social media, museum storytellers incorporate their approach not as merely passive writings, but fostering a possibility of making an active participation in creating an open-ended version of story that keeps on growing.

In addressing these digital-age transformations impacting museums, Bautista (2014) introduced the concept of “modern museology,” advocating for a deeper understanding of this shift — specifically by examining four core constructs closely interconnected in the digital age: place, community, culture, and technology. These elements converge in an increasing awareness that personal mobile technology has become an extension of art institutions, enabling visitors to engage with the museum experience wherever and whenever they wish. For storytellers crafting narratives specifically for online platforms, understanding the unique user base of each platform is essential — emphasising that writing a story involves more than focusing solely on the object itself. It requires awareness of the context in which the story will be presented, the target audience, and the appropriate approach for effective engagement.

E. Conclusion

The role of the museum storyteller has emerged as a vital function within the broader creative industry, occupying a unique position at the intersection of cultural heritage, technological innovation, and audience engagement. In the current museum landscape, storytelling has expanded well beyond the confines of traditional object labels, aligning with practices in fields such as copywriting, content development, and digital marketing. This alignment highlights the storyteller’s role as one that not only imparts knowledge but also inspires and fosters personal connections with heritage. In doing so, museum storytellers operate similarly to brand strategists, crafting narratives that resonate on a deeply emotional and individual level, engaging visitors in ways that simple factual recounting cannot achieve.

With advancements in technology, especially in areas like generative AI, museum storytellers encounter both potential benefits and challenges. While AI can optimise certain tasks, such as generating text or synthesising information, it often lacks the nuanced understanding of cultural context and personal insight required for meaningful storytelling. For instance, institutions like The Burrell Collection demonstrate how the museum storyteller’s approach goes beyond mere description, employing empathy and audience-centred narratives that invite emotional engagement and contribute to a more holistic and accessible interpretation of cultural heritage.

In an increasingly digital environment, museum storytellers must embrace skills widely shared within the creative industry, such as developing personalised content and adapting style and tone to suit various platforms, from social media to on-site displays. However, the human element remains irreplaceable, as it ensures that storytelling is rooted in cultural sensitivity and an awareness of audience diversity. This human-centred approach reinforces the museum’s educational mission, ensuring that storytelling remains an essential and transformative force within the digital age, where museums act not only as repositories of objects but as facilitators of meaningful cultural dialogue. Through this integration, museum storytelling asserts its role as an influential practice within the evolving landscape of the creative industry.

Reference List

- Akker, van den C. & Legêne, S. 2016, Museums in a Digital Culture: How Art and Heritage Become Meaningful in Akker, van den C. & Legêne, S. (eds), Museums in a Digital Culture. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 7-1.

- Barker, R. 2019, “Creatives talk technology: exploring the role and influence of digital media in the creative process of advertising art directors and copywriters”, Media Practice and Education, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 244-259.

- Bautista, S.S. 2014, Museums in the Digital Age: Changing Meanings of Place, Community, and Culture, Altamira Press, Lanham, Maryland; Plymouth, England.

- Hernández, E. & SpringerLink (Online service) 2017, Leading Creative Teams: Management Career Paths for Designers, Developers, and Copywriters, Apress, Berkeley, CA.

- Langer, A. & American Alliance of Museums 2022, Storytelling in Museums, Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham.

- McLeod, C., O’Donohoe, S. & Townley, B. 2009, “The elephant in the room? Class and creative careers in British advertising agencies”, Human Relations, vol. 62, no. 7, pp. 1011-1039.

- Moorhead, J. 2023, “The Burrell Collection: the recently reopened Glasgow museum is asking fresh questions of its objects and its audience”, The Art Newspaper. Available at: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/07/10/the-burrell-collection-the-recently-reopened-glasgow-museum-is-asking-fresh-questions-of-its-objects-and-its-audience (Accessed 12 October 2024).

- The Burrell Collection, 2023. Community Involvement. Available at: https://burrellcollection.com/burrell-project-stories/community-involvement/ (Accessed 12 October 2024).

- Timothy, D.J. 2021, Cultural Heritage and Tourism: An Introduction, second edition, Channel View Publications, Bristol; Blue Ridge Summit.

- Vicsek, L., Pinter, R. & Bauer, Z. 2024, “Shifting job expectations in the era of generative AI hype – perspectives of journalists and copywriters”, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy.