By Melissa Ho

Secondhand shopping is an activity that has been around for a long time, not only to save costs, but also as a way of decreasing one’s carbon footprint.1 As the fashion industry has become fast-paced and overconsumption behavior worsens, resources are at risk of becoming obsolete and companies’ search for cheap manufacturing leads to exploitation of laborers in the Global South, while polluting the environment with an abundance of textile waste dumped in landfills.2 Consumer’s increasing awareness of the effect of the fashion industry pushes scholars, companies and consumers themselves to search for a more sustainable way of producing, distributing and consuming fashion.

For decades, different design industries have been using the strategy of planned obsolescence to stimulate consumers to keep purchasing new products.3 Planned obsolescence exists in different forms: the purposely faulty made products or materials that last for a limited amount of time, and the social aspect of planned obsolescence which creates trends and the social need to keep up with the taste of the majority of society.4 As companies plan for products to ‘expire,’ the waste accumulates until it does irreversible damage to the earth and its inhabitants. In the case of fast fashion, at its current understanding, it is about fast and cheap consumption of new items, while sustainability aims for long lasting and durable design and products.5

In approaching the consequences of wasteful industries, different scholars have proposed and advocated for a circular economy (CE). According to Kopnina, CE relies on the concept of circularity, which “entails reducing if not completely eliminating the consumption of new (raw) materials and designing products in such a manner that they can easily be taken apart and reused after use.”6 As the fashion industry has become globalized and destructive, to achieve CE, systematic change and collaboration between all levels – design, manufacturing, distribution, consumption – within the industry is crucial.

In addition, studies of consumption behavior and the consumer’s needs are essential in finding solutions to the pressing problems, since consumers may be able to direct or influence the production or distribution process by demanding for change. The assessment of the needs of the different stakeholders is essential to understand and overcome the obstacles of practicing a more sustainable form of fashion.

One of the examples of a circular form of shopping is secondhand, which is increasingly gaining momentum in popularity among youth.7 As Palomo-Domínguez et al. have described, this type of shopping offers possibilities to curate a unique self identity, while recognizing and confronting the environmental impact of the fashion industries.8 Within the globalized and digital world, different mobile marketplace applications have been developed. The secondhand shopping platform, Vinted, has risen in popularity from 2008 onwards, when it was founded in Lithuania. Starting out with the mission “to make second-hand the first choice worldwide,”9 the company has expanded to more than 20 different countries and has been downloaded by millions.10 As the application is intended to promote sustainable and slow fashion, but could also have less sustainable implications, this paper will both highlight the possibilities and the weaknesses of keeping the promise of sustainability through online secondhand shopping.

Literature research will indicate what the motivations for online secondhand shopping may be and how the consideration of environmental and ethical sustainability are taken into account while consuming fashion. Vinted will be analyzed according to the interface design and connected to the concepts proposed in existing research. The following research question will be studied: In the context of the process of a sustainable future of the fashion industry, to what extent is digital platform Vinted contributing to the transformation of secondhand shopping into a commodified practice?

Reviewing literature: conceptualization of the proposed solutions

The main motivation for purchasing clothes is, as Atik and Ertekin have argued, the desire for newness. While this could be applicable to any product, fashion items are for many people an important symbolic medium to express their self-identity or conform to the norms and values of the larger community.11 The restless desire for newness could also be explained by the empty promises from the media and mass-distributed trends, and boredom resulting in the need for novelty, even when this is elusive.12 While this desire for newness depends on the individual, fast fashion corporations like H&M and Zara are not innocent and fuel this hunger by mass producing new collections of clothes, every month or even week, with a limited availability, pressuring consumers to follow the newest trends. The overconsumption leads to the normalization of disposing of clothes at a faster rate.13

Atik and Ertekin emphasize the lack of emotional connection, or the personal affect, consumers have in regards to their personal belongings and how this makes its disposal even easier.14 In this way, the fast fashion industry not only harms the health of workers and the environment, but it also pollutes the consumer’s mind.

Fashion as a sustainable practice has ambiguous connotations, even within the academic field. To clear up misunderstandings, West et al. have argued for the term slow fashion to describe a type of fashion that “is not reliant on things that are new, it is not obsessed with image, neither is it delivered top down from designers through the catwalk and then emulated by fast fashion retailers.”15 They urge consumers to break with current consumption behavior, where quality over quantity is valued. Instead of following trends, fashion should reflect the consumer’s individual creative choice.16 However, in reality this goal is hard to achieve considering the many factors that contribute to the greater problem.

A circular fashion industry is usually considered from a macro-level, top-down perspective where companies and policymakers are expected to take the initiative to make meaningful changes. Circular economy’s (CE) main goal is to provide an alternative for the linear form of production and economy, which refers to products being made to end up as waste.17 As Mishra, Jain and Malhotra have argued, achieving CE requires radical systematic changes throughout the whole value chain, in order to transform waste back to resources.18 CE in fashion could manifest itself through designers and big fashion brands designing garments that “use sustainable raw materials, close the material loops and keep the material and products in the loop, as long as possible”19 with the help of innovation and collaboration between different levels of stakeholders. As certain fashion designs are made with the ‘resilience’ value in mind, Vanacker et al. believe that kind of “product has a high ability to adapt to changing environments.” 20However in reality, if the current system is lucrative enough, the question remains if companies within the fashion industry feel impelled to radically and systematically rethink and redo their way of producing and supplying fashion.

On the other hand, CE could also be approached from a bottom to top strategy. Different scholars have argued and urged for a bottom up approach to slowing fashion down by understanding consumption behavior and proposing different solutions suited for each type of consumer. West et al. have defined different types of consumers and urge to design the transformation to slow fashion according to those differences. They have observed the following types of consumers through interviews: the hierarchist, egalitarian and the individualist. The hierarchist understands slow fashion as a collective responsibility, and if not everyone is participating, they do not feel obliged to do the same. The egalitarian considers every stage of the fashion production and supply chain and the implications their role and responsibility has on the present and future. Lastly, the individualist approaches fashion based on individual choice, narrative and values, which suggests that this type does not consider slow fashion as a personal responsibility if it is not included in their personal values and they may consider other elements, like style, more important.21

In the context of online secondhand shopping, or thrifting, this activity has been made possible through digitalization and globalization. Through a digital platform, the physical, local vintage or thrift shop transforms into an online marketspace available to a greater audience. Individuals are able to curate their used “closet” and directly exchange secondhand items between each other.

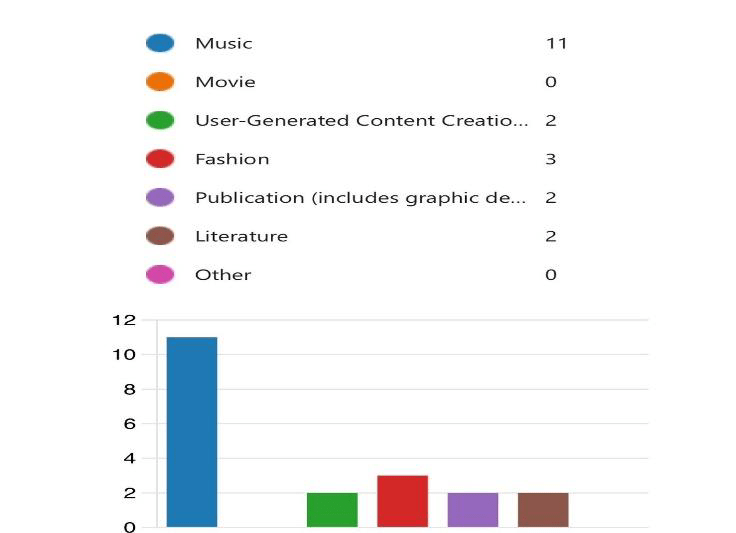

Vinted is currently one of the most popular online resale platforms on the market.22 In mainstream media, Vinted commercials promote the platform and simultaneously the idea of consumption and the reuse of garments,23 using slogans like ‘Don’t wear it? Sell it!’ The app is believed to contribute to Gen Z’s (born from 1995 to 2009) motivation and understanding of sustainable fashion as Palomo-Domínguez et al. have argued.24 They describe Gen Z as digital natives; the generation that exists in and is influenced by online spheres. When expanding their knowledge on the impact of the fashion industry on the environment Gen Z tends to depend on the media and trends they consume.25 In regard to Vinted, a part of the participants in Palomo-Domínquez et al. ‘s focus group interviews appreciated Vinted’s contribution to sustainability and gained motivation to act in the same manner, but also considered it as trendy.26 From their research, the authors have obtained consistent findings in which “despite Gen Z’s environmental and sustainable awareness, this generation still presents a majoritarian consumption behavior that supports fast fashion and other non-sustainable models.”27 The majority of the participants who use Vinted prioritized practical attributes like making and saving money, decluttering and the ease of using the platform.28 Thus, while Gen Z becomes increasingly aware of sustainability and the downsides of the (fast) fashion industry, scholars observe an action-value gap.29

While different studies have proposed practical solutions to a complex problem, there is not one way in which it can be tackled. However, there are a few commonalities: slow fashion and emotional durability seem to express the most important components of a sustainable fashion practice. In the case of (online) secondhand shopping, one might wonder if this type of shopping fulfills these needs or exploits them. Cerio et al. argue in their article that platforms like Vinted are over-marketized, causing conflicts between users on secondhand resale platforms. Conflicts regarding market-related topics are the most common, as most users on these platforms value economic aspects (e.g. bargaining) and convenience (e.g. ease of use) the most, favor a competitive atmosphere and consequently often experience negative social exchanges.30 However, this argument becomes more nuanced, as Ceria et al. argue, since consumers are able to adapt to others who may not have the same commercial intentions, and so they are able to rely on “domestic values, such as politeness and trust, which ultimately work to de-commodify commodity practices.”31

Method

By using the walkthrough method in an interface analysis, the format of the app Vinted will be studied from the perspective of the user’s experience. As Light et al. have stated, this method enables the researcher to establish a corpus of data to study the technical and cultural implications embedded in an app.32 This type of analysis offers insights on the intended use of the app and how the interface may or may not influence the user’s behavior. Using the walkthrough method for Vinted may offer meaningful results, as it indicates how both the company and the consumer have agency over their choice and at the same time influence the outcome of each other’s actions. The collected data will be further discussed in the discussion in relation to the literature review.

Vinted: an online thrifting experience33

Vinted’s expected use in three stages

The first stage entails the app’s vision, which refers to “the purpose, target user base and scenarios of use, which are often communicated through the app provider’s organizational materials.”34 Vinted Marketplace claims on their official website that they want “to make second-hand the first choice worldwide” by extending the lifecycle of its member’s used items.35

The operating model, the second stage of determining an app’s expected use, is based on the “business strategy and revenue sources, which indicate underlying political and economic interests.”36 Vinted gains their incentives through advertisements in the app and the amount of downloads they have achieved worldwide. Users do not have to pay for the app nor do they have to pay the company to place orders or sell products. As a secondhand marketplace, there is some implication that they disagree with the current production and consumption cycle, and in this way want to offer alternative consumption behavior, where extending the lifecycle of an item is desired.

Lastly, the third stage involves the modes of governance, or in other words, the ways “the app provider seeks to manage and regulate user activity to sustain their operating model and fulfill their vision,” which is based on documents like guidelines and the Terms of Services.37 Vinted has set rules to ensure that the platform is a “friendly and safe place to trade secondhand items.”38 They request users to comply with the list of items that are allowed to be put for sale and refer to official rules from the European Economic Area. In the guidelines there is a list of prohibited items and a declaration that Vinted has the right to re-evaluate what items are or are not allowed to be listed. If certain items are found to be unsafe or inappropriate, Vinted may remove these items. Additionally, users are given the agency to report incidents of listings of prohibited items.39

Walkthrough method

Registering and entering Vinted

Upon opening Vinted, the user is met with a regular registration system, in which they fill in their information or log in using an existing Google or Facebook account. Once registered, the user enters the platform and is met with Vinted’s minimalist and straightforward interface design on their home page. At the top of the screen there are three categories shown: “Everything,” “Designer” and “Electronics.” Depending on each category, a new page with different items is shown.

On the bottom of the screen the following buttons show different screens: “Home,” “Search,” “Sell,” “Inbox” and “Profile.” The design and affordances of the app offer basic actions for users to follow to browse through items and sell their clothes.

Everyday use40

When scrolling down the “Everything” page, the following topics with fitting images are shown: “Recommendations for you,” “Your favorites,” “Last viewed items.” These categories indicate the app’s ability to adapt to the tastes of the user based on their recorded behavior on the platform. Simultaneously, suggested items suiting the user’s taste may encourage more consumption.

After scrolling down, the category “New” appears and a roster of newly listed items offers the user an overview of what can be bought. The large number of Vinted users results in frequent updates of newly uploaded items. Each item is visualized with an image, the username of the seller, the size, brand and the price of an item. Users are able to “like” the items that they are interested in and they are able to see the amount of likes, or in other words the amount of people interested in a particular item, which may cause pressure to purchase the item before someone else does.

Once the user finds an item that they have taken interest in, they can click on the image and the item appears in a larger size on screen. When scrolling down, the user finds the seller and their reviews symbolized in a five-star system, a description of the item and additional information (e.g. shipping, extra security fees), and more images of items that the seller offers. In this way, the user is able to hunt for more items from one seller’s “closet.” Buying more from one seller becomes a “bundle” and is rewarded with a discount. However, if the user is interested in a singular item, they could simply buy the item or make an offer. The process of negotiation is private between the buyer and the seller through direct messaging, which can be found in the “Inbox.”

Discontinuation of use

By ‘walking through’ Vinted, the discontinuation of using the app is difficult to generalize for every user. However, a few possible reasons can be imagined. Firstly, in the future, secondhand shopping may not be considered to be as trendy anymore as it is right now, causing this form of shopping to become less desired. Additionally, the “newness” of items or the amount of “new” items that are uploaded may become obsolete or less frequent, decreasing the interest to regularly check the content of the app. This could become the case if another app or platform enters the market that may offer different affordances or different products that are more favorable. Ceria et al. have argued that negative social exchanges between users have resulted in refusing or abandoning the use of the platform, and donating the items somewhere else instead.41 Lastly, if slow fashion will be accomplished someday, the desire for newness may get subdued and users become more conscious of their consumption behavior, which may cause lesser use of the app.

Discussion and conclusion

From the findings of the interface analysis, Vinted can be considered a platform that encourages a conscious way of consuming while destigmatizing secondhand shopping, putting purchasing used items in a positive light and encouraging less textile waste. At the same time, Vinted also sustains a market-focused view on shopping, and possibly overconsumption. The international and easy-to-use nature of the platform together with an online shopping experience may afford the user to gain more accessibility and prolong the desire for newness. Consumers long for self-actualization; they want to be able to curate their own unique self through fashion. The access to individuals’ “closets” from over different countries means a wider variety of unique items, but also the thrill of acquiring garments for a bargain, may make Vinted an attractive app for those users. At the same time, the existence of the app could enable consumers to buy items firsthand while considering the fact that they could always resell it, opposed to donating the items to a local charity shop or purchasing used items. Secondhand shopping is considered to be sustainable, but if it becomes excessive consumption where the individual’s values are prioritized, the outcome may not comply with the goal of CE.

The consumer’s behavior may further commodify the thrifting experience, if consumers consider Vinted as a revenue model. For instance, buying used items, that might be trending or rare luxury finds, in bulk and reselling these items for a higher price could lead to the gentrification of secondhand shopping, meaning that the prices within the thrift and charity shops increase and people with lower income may find it harder to afford. However, it is crucial to note that this discussion as of right now mainly consists of hypotheses that have to be studied with the support of qualitative and quantitative research. Qualitative research, like interviews, could further explore the perceptions that Vinted users may have on the changing experience of secondhand shopping. As Gen Z is influenced by social media, it also might be recommended to study how Vinted markets themselves, how Gen Z portray and promote Vinted in their own content, and how this could affect the perception of sustainability in fashion.

All in all, this paper has offered insights into the concepts clouding the process of making the fashion industry more sustainable. While existing literature has proposed different solutions to companies, designers, artisans, policymakers and consumers, the interface analysis in this paper has shown that current consumption behavior could be continued to be encouraged through the app’s design. In Vinted’s case, it could be argued that the platform affords users to translate their consumption behavior in the setting of the app. While some consumers may be genuine about contributing to the common good, others may use secondhand items as an excuse to continue their excessive consumption. Thus, considering the nature of the platform, in addition to the design of the app which promotes the “new” and personalization, and the use of buying and selling as the main strategy in their marketing, it could be argued that Vinted may fuel the consumer’s desire for newness.

To conclude, platforms like Vinted should attempt to alter their business model in order to create and enable conscious shopping in which the needs of consumers are satisfied without their desire for the new and the material. However, aiming for a circular economy cannot be achieved from an industry standpoint only, consumers are needed to break cycles of unethical and unsustainable practices, and so, a solution is not only a one-way street but a complex web of intertwining and intersecting stakeholders.

Bibliography

- Atik, Deniz, and Zeynep Ozdamar Ertekin. “The Restless Desire for the New versus Sustainability: The Pressing Need for Social Marketing in Fashion Industry.” Journal of Social Marketing 13, no. 1 (2023): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-02-2022-0036.

- Bae, Su Yun and Ruoh-Nan Yan. “Comparison between Second-Hand Apparel Shoppers versus Non-Shoppers: The Perspectives of Consumer Ethics.” International Journal of Environmental & Science Education 13, no. 9 (2018): 727-736. e-ISSN: 1306-3065. http://www.ijese.net/makale_indir/IJESE_2082_article_5be1e044a16f3.pdf.

- Balińska, Agata, Ewa Jaska, and Agnieszka Werenowska. 2024. “The Importance of the Vinted Application in Popularizing Sustainable Behavior among Representatives of Generation Z.” Sustainability 16, no. 14 (2024): 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146213.

- Cerio, Eva, Alain Debenedetti and Rieunier Sophie. “When the secondhand economy is not as good as it seems: understanding conflicts and their (ir)resolutions between users on secondhand resale platforms.” Qualitative Market Research 1, no.1 (2024): 1-21. https://doi-org.vu-nl.idm.oclc.org/10.1108/QMR-05-2023-0069.

- Dana, Leo Paul, Rosy Boardman, Aidin Salamzadeh, Vijay Pereira, and Michelle Brandstrup. Fashion and Environmental Sustainability: Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Technology. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2024. https://www.degruyter.com/isbn/9783110795431.

- Fletcher, Kate. “Durability, Fashion, Sustainability: The Processes and Practices of Use.” Fashion Practice 4, no. 2 (2012): 221–38. https://doi.org/10.2752/175693812X13403765252389.

- Kollmuss, Anja and Julian Agyeman. “Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior?” Environmental Education Research 8, no. 3 (2002): 239–260.

- Kopnina, Helen, and Kim Poldner. Circular Economy: Challenges and Opportunities for Ethical and Sustainable Business. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2022. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN= 2914860.

- Light, Ben, Jean Burgess and Stefanie Duguay. “The walkthrough method: An approach to the study of apps.” New Media & Society 20, no. 3 (2018): 881-900. https://doi-org.vu-nl.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/1461444816675438.

- Mishra, Sita, Sheetal Jain, and Gunjan Malhotra. “The Anatomy of Circular Economy Transition in the Fashion Industry.” Social Responsibility Journal 17, no. 4 (2021): 524–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-06-2019-0216.

- Palomo-Domínguez, Isabel, Rodrigo Elías-Zambrano, and Víctor Álvarez-Rodríguez. “Gen Z’s Motivations towards Sustainable Fashion and Eco-Friendly Brand Attributes: The Case of Vinted.” Sustainability 15, no. 11 (2023): 1-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118753.

- Ritch, Elaine L. “Experiencing Fashion: The Interplay between Consumer Value and Sustainability.” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 23, no. 2 (2020): 265–85. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-09-2019-0113.

- Vanacker, Hester, Andrée-Anne Lemieux, and Sophie Bonnier. “Different Dimensions of Durability in the Luxury Fashion Industry: An Analysis Framework to Conduct a Literature Review.” Journal of Cleaner Production 377 (2022):1-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134179.

- Vinted. “About Vinted.” Accessed October 10, 2024. https://careers.vinted.com/company.

- Vinted. “Catalog rules.” Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.vinted.com/catalog-rules?srsltid=AfmBOooyHehpGPegSPnOOy_Xdr9vcl4-Zn7 vCf7nPKTXQhN4Mia2M8Sc.

- Vinted. “Too Many? | Vinted.” Youtube. Uploaded on May 24, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6ZDnpoEoOU.

- West, Jodie, Clare Saunders, and Joanie Willet. “A Bottom up Approach to Slowing Fashion: Tailored Solutions for Consumers.” Journal of Cleaner Production 296, no.1 (March 2021): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126387.

Footnotes

- Su Yun Bae and Ruoh-Nan Yan, “Comparison between Second-Hand Apparel Shoppers versus Non-Shoppers: The Perspectives of Consumer Ethics,” International Journal of Environmental & Science Education 13, no. 9 (2018): 728. e-ISSN: 1306-3065.

↩︎ - Leo Paul Dana, Rosy Boardman, Aidin Salamzadeh, Vijay Pereira, and Michelle Brandstrup. Fashion and Environmental Sustainability: Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Technology (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2024), 134-7. https://www.degruyter.com/isbn/9783110795431. ↩︎

- Helen Kopnina and Kim Poldner, Circular Economy : Challenges and Opportunities for Ethical and Sustainable Business (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2022), 2.

↩︎ - Kate Fletcher, “Durability, Fashion, Sustainability: The Processes and Practices of Use,” Fashion Practice 4, no. 2 (2012): 222-25. https://doi.org/10.2752/175693812X13403765252389. ↩︎

- Deniz Atik, and Zeynep Ozdamar Ertekin, “The Restless Desire for the New versus Sustainability: The Pressing Need for Social Marketing in Fashion Industry,” Journal of Social Marketing 13, no. 1 (2023): 1, https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-02-2022-0036.

↩︎ - Kopnina and Poldner, Circular Economy, 1. ↩︎

- Isabel Palomo-Domínguez, Rodrigo Elías-Zambrano, and Víctor Álvarez-Rodríguez, “Gen Z’s Motivations towards Sustainable Fashion and Eco-Friendly Brand Attributes: The Case of Vinted,” Sustainability 15, no. 11 (2023): 2, https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118753.

↩︎ - Palomo-Domínguez, Elías-Zambrano and Álvarez-Rodríguez, “Gen Z’s Motivations towards Sustainable Fashion and Eco-Friendly Brand Attributes,” 3. ↩︎

- “About Vinted,” Vinted, accessed October 10, 2024, https://careers.vinted.com/company. ↩︎

- CI research paper

Vinted, “About Vinted.” ↩︎ - Atik and Ertekin, “The Restless Desire for the New versus Sustainability,” 3. ↩︎

- Atik and Ertekin, “The Restless Desire for the New versus Sustainability,” 3. ↩︎

- Atik and Ertekin, “The Restless Desire for the New versus Sustainability,” 5. ↩︎

- Atik and Ertekin, “The Restless Desire for the New versus Sustainability,” 5. ↩︎

- Jodie West, Clare Saunders and Joanie Willet, “A Bottom up Approach to Slowing Fashion: Tailored Solutions for Consumers,” Journal of Cleaner Production 296, no.1 (March 2021): 2, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126387. ↩︎

- West, Saunders and Willet, “A Bottom up Approach to Slowing Fashion,” 2. ↩︎

- Kopnina and Poldner, Circular Economy, 1. ↩︎

- Sita Mishra, Sheetal Jain and Gunjan Malhotra, “The Anatomy of Circular Economy Transition in the Fashion Industry,” Social Responsibility Journal 17, no. 4 (2021): 527, https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-06-2019-0216. ↩︎

- Mishra, Jain and Malhotra, “The Anatomy of Circular Economy Transition in the Fashion Industry,” 526. ↩︎

- Hester Vanacker, Andrée-Anne Lemieux, and Sophie Bonnier, “Different Dimensions of Durability in the Luxury Fashion Industry: An Analysis Framework to Conduct a Literature Review,” Journal of Cleaner Production 377 (2022): 1, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134179. ↩︎

- West, Saunders and Willet, “A Bottom up Approach to Slowing Fashion,” 5. ↩︎

- Palomo-Domínguez, Elías-Zambrano and Álvarez-Rodríguez, “Gen Z’s Motivations towards Sustainable Fashion and Eco-Friendly Brand Attributes,” 5. ↩︎

- Vinted, “Too Many? | Vinted,” Youtube, uploaded on May 24, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6ZDnpoEoOU. ↩︎

- Palomo-Domínguez, Elías-Zambrano and Álvarez-Rodríguez, “Gen Z’s Motivations towards Sustainable Fashion and Eco-Friendly Brand Attributes,” 2. ↩︎

- Agata Balińska, Ewa Jaska, and Agnieszka Werenowska, “The Importance of the Vinted Application in Popularizing Sustainable Behavior among Representatives of Generation Z,” Sustainability 16, no. 14 (2024): 2, https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146213. ↩︎

- Palomo-Domínguez, Elías-Zambrano and Álvarez-Rodríguez, “Gen Z’s Motivations towards Sustainable Fashion and Eco-Friendly Brand Attributes,” 16. ↩︎

- Palomo-Domínguez, Elías-Zambrano and Álvarez-Rodríguez, “Gen Z’s Motivations towards Sustainable Fashion and Eco-Friendly Brand Attributes,” 16. ↩︎

- Palomo-Domínguez, Elías-Zambrano and Álvarez-Rodríguez, “Gen Z’s Motivations towards Sustainable Fashion and Eco-Friendly Brand Attributes,” 16. ↩︎

- Anja Kollmuss and Julian Agyeman, “Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior?” Environmental Education Research 8, no. 3 (2002): 242. ↩︎

- Eva Cerio, Alain Debenedetti and Rieunier Sophie, “When the secondhand economy is not as good as it seems: understanding conflicts and their (ir)resolutions between users on secondhand resale platforms,” Qualitative Market Research 1, no.1 (2024): 16, https://doi-org.vu-nl.idm.oclc.org/10.1108/QMR-05-2023-0069. ↩︎

- Cerio, Debenedetti and Sophie, “When the secondhand economy is not as good as it seems,” 17. ↩︎

- Ben Light, Jean Burgess and Stefanie Duguay, “The walkthrough method: An approach to the study of apps,” New Media & Society 20, no. 3 (2018): 882, https://doi-org.vu-nl.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/1461444816675438. ↩︎

- This analysis was conducted on the 16th of October, 2024. ↩︎

- Light, Burgess and Duguay, “The walkthrough method,” 889. ↩︎

- Vinted, “About Vinted.” ↩︎

- Light, Burgess and Duguay, “The walkthrough method,” 890. ↩︎

- Light, Burgess and Duguay, “The walkthrough method,” 890. ↩︎

- “Catalog rules,” Vinted, accessed October 10, 2024, https://www.vinted.com/catalog-rules?srsltid=AfmBOooyHehpGPegSPnOOy_Xdr9vcl4-Zn7vCf7nPKT XQhN4Mia2M8Sc. ↩︎

- Vinted, “Catalog rules.” ↩︎

- Due to the limited scope of the paper, only a few aspects of the app will be discussed. ↩︎

- Cerio, Debenedetti and Sophie, “When the secondhand economy is not as good as it seems,” 17. ↩︎