By Hana Arshid

Introduction

Prior to the World Wide Web boom, the music industry engaged in media-driven activism and humanitarian aid through broadcasted concerts and tours, exemplified by the high-profile Band Aid and Live Aid events of the 1980s, which raised millions for Ethiopian famine relief. These celebrity-driven initiatives were criticised by both Müller (2013) and Jones (2017), who argue that celebrity humanitarianism feeds a form of marketised philanthropy that oversimplifies complex socio-political issues. They contend that Band Aid and Live Aid, through media-driven activism, employed neocolonial representations of Africa to evoke emotional responses by focusing on pity, rather than addressing the structural causes of crises (Müller, 2013; Jones, 2017). This approach advanced a depoliticised narrative, which transformed activism into what Douzinas (2007) calls “a consumer spectacle” centred on mass appeal and individual donations, ultimately reinforcing neoliberal ideals. These efforts sustained global power dynamics that perpetuated existing inequalities rather than propelling systemic change.

The advent of music platformisation has altered the industry’s approach to humanitarian and advocacy efforts. While celebrity-driven humanitarianism remains prevalent, platforms like Bandcamp—described by Hesmondhalgh et al. (2019) as quasi-platforms—give musicians both a way to sustain their careers and a direct avenue to engage in advocacy through the sale of digital and physical music, as well as merchandise. This sets it apart from massive conglomerates like Spotify, and larger platforms such as SoundCloud, which is gradually embracing the economic model of streaming giants. Suárez (2012) maintains that smaller entities are more likely to advocate for social justice and lend legitimacy to nonprofits working for social change. Bandcamp’s model reflects this perspective, with independent musicians and labels collaborating with relief NGOs to raise funds for humanitarian crises and show solidarity.

Several characteristics render Bandcamp particularly well suited to these endeavours, foremost among which is its commitment to an independent ethos. This resonates with independent musicians who seek to distance themselves from the corporate frameworks that dominate the mainstream music industry—a sector notorious for failing to adequately compensate artists for their labour. The producer-oriented platform endorses a moral economy, where consumer interests converge with musicians’ welfare (Hesmondhalgh et al., 2019; Rogès, 2024), thus appealing more to niche audiences than to the mass market. Appadurai’s (2012) theory of “the social life of commodities” is relevant here: a commodity’s value arises from the social interactions and exchanges that shape it. In the context of Bandcamp fundraisers, the value of music as a commodity is not solely anchored in the artistic work itself but extends to the causes that it endorses and the bonds it establishes between audiences and humanitarian initiatives.

Since October 2023, there has been a notable proliferation of art- and music-based fundraisers for Gaza, with strong engagement from the Bandcamp community, in response to the escalating humanitarian crisis precipitated by the large-scale Israeli bombardment and the total siege of the territory. This essay explores how cultural production through fundraising on Bandcamp creates social and economic value within the digital platform economy, amidst the complexities of digital activism and humanitarianism, and the commodification of suffering. Using distant reading and sentiment analysis, the study examines the rhetorical appeals in 30 record-label fundraisers published between October 2023 and October 2024. It also probes the degree to which these fundraisers reinforce traditional media-driven humanitarian paradigms akin to those epitomised by Band Aid, and where they challenge and deconstruct these established traditions.

Methodology

The study integrates quantitative research methods with qualitative analysis of the derived data. It implements a distant reading algorithm, written in Python, to process textual data from 30 Bandcamp record-label pages, utilising the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) library, which offers a suite of tools for natural language processing (NLP). This statistical approach corresponds well with the complex and manifold nature of the fundraisers’ discourses (advocacy, promotion, genre-specific language). It enables the exploration of the corpus through a more ecologically valid lens that provides an objective measure of key metrics and minimises the impact of human intuition and subjectivity (Allen et al., 2020: 5), thus enhancing data reliability.

NLP facilitates the extraction of insights from large text datasets, like Bandcamp fundraisers, through techniques such as sentiment analysis, topic detection, and recognition of named entities and relationships within texts (Kibble, 2013). The algorithm tokenises the text into individual words, removes common stopwords, and counts word frequencies. With the NLTK library as a foundation, additional algorithms were devised to conduct bigram analysis, identifying word correlations through the detection of frequently co-occurring word pairs, in addition to sentiment analysis.

Charts and maps serve as the primary visualisation methods. Knowledge visualisation effectively communicates research to the public, supports integrated learning on complex problems, and nurtures relational perception (Boehnert, 2016). Python code is used to map the locations of record labels involved in fundraising for Gaza by assigning geographic coordinates and continent-based colours. The data is dynamically visualised on a Folium map to display location frequencies, while word frequencies, bigrams, and sentiment analysis are visualised through bar charts generated by Matplotlib.

As for the selection criteria for the 30 Bandcamp fundraisers, they include those launched between October 2023 and October 2024, appearing in the top results for the keywords “Gaza” and “fundraise,” and containing a clear statement of purpose beyond just the use of keywords in the title.

Political Consumerism and the Appeal for Credibility

Bandcamp fundraisers motivate record-label fans to leverage their purchasing power as a form of political engagement in the digital sphere. George and Leidner (2019) categorise digital political engagement into three tiers—spectator, transitional, and gladiatorial—based on Milbrath’s (1981) hierarchy of political participation. Bandcamp fundraisers fit into medium-effort political engagement, as they involve two types of transitional activities: political consumerism and e-funding (George and Leidner, 2019; Ward and Vreese, 2011). These activities, unlike minimal-effort spectator activities, require greater resource allocation and financial contributions from participants. Purchases of music records, framed as contributions to relief and advocacy efforts for Gaza, is an example of political consumerism, which Ward and Vreese (2011: 402) define as an individualised collective action where “consumer choice of producers and products is based on their alignment with personal, political or ethical considerations.”

Political consumerism on Bandcamp manifests through diverse forms of e-funding. For instance, the Moot Tapes label fundraiser in Ireland promotes what George and Leidner (2019) refer to as “e-funding through direct donations” to a partner on-the-ground relief NGO. Consumers who provide proof of donation receive free access to the label’s album, which was created specifically for fundraising. Alternatively, the label offers a “name your price” option, allowing supporters to purchase the album without necessarily donating to the partner NGO. Whether or not the album purchase supports NGOs in Gaza, its value and circulation as a commodity are shaped by politics and an association with relief efforts. The music album operates within what Appadurai (2012) terms “regimes of value,” the cultural, social, and historical frameworks that regulate the classification and exchange of such commodities (Appadurai, 2012: 83-84).

Figure 1: Top 20 Relief-Related Bigrams (Arshid, 2024)

Bandcamp fundraisers cultivate political consumerism through a complex interplay of trust-building mechanisms. Neilson and Paxton (2010) found a negative correlation between political consumerism and trust in institutions and official bodies; it is, meanwhile, positively linked to generalised trust, that is, societal trust, including in grassroots and independent initiatives. The collaboration between independent musicians and humanitarian institutions enhances the credibility of the fundraisers, particularly at a time when, as Sharma (2017) argues, humanitarian organisations, now functioning as brands, struggle to maintain moral authority due to their perception as commercial entities.

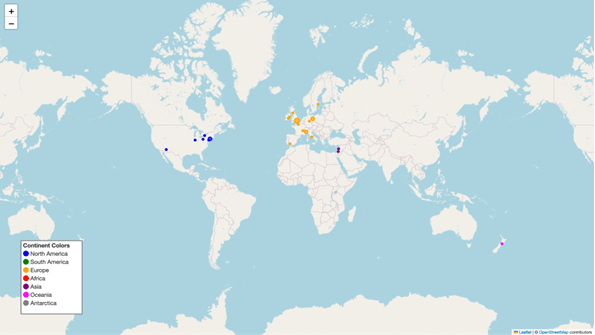

An additional pillar of trust-establishment is the use of rhetorical devices intended to boost credibility. The distant reading of the fundraiser statements indicates a merger of immediate humanitarian aid with long-term advocacy discourse to form a dual-purpose appeal. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate that advocacy terms such as “liberation,” “human rights,” “solidarity,” “freedom,” and “justice” do not dominate the frequency counts to the same extent as the terms directly associated with relief. Thus, fundraisers achieve their appeal for credibility primarily by showcasing direct, short-term impact and addressing urgent needs. To enhance legitimacy for this appeal, the fundraisers align themselves with broader justice-oriented demands by drawing on terminology rooted in universally recognised values, in a bid to evoke emotional and moral responses from supporters. The advocacy-related bigrams likewise highlight the overarching theme of collective action. This “collective identity,” stemming from a “shared sense of ‘we-ness’ and ‘collective agency’” (Snow, 2001: 2212), is a strong emotional motivator for participation in donations. The blend of ethos and pathos in the fundraiser discourse aims to engineer consent (Herman and Chomsky, 1988) from supporters by reassuring them that their buy-in will generate sustainable justice, in addition to providing urgently needed relief.

Figure 2: Top 20 Advocacy-Related Bigrams (Arshid, 2024)

Notably, the moral sentiments underpinning classical humanitarian discourse, such as compassion and empathy, are not explicitly invoked as rhetorical devices within the fundraisers. However, terms like “children relief” carry an implicit emotional appeal, as they suggest helping vulnerable populations, evoking feelings of compassion and empathy. Sharma (2017: 3-4) proposes that these sentiments are “asymmetrical feelings” that may reinforce social and geopolitical hierarchies between benefactors (in the global North) and recipients (in the global South). The emotional and moral appeal of the Bandcamp fundraisers is not rooted in mere sympathy evocation; rather, it situates advocacy within the discourse of human rights and global solidarity, potentially generating another form of asymmetrical sentiment. This approach positions victims as subjects of universal human rights narratives, rather than individuals grounded in their specific geographic or cultural contexts (Nayar, 2009).

The Geopolitics of Humanitarianism and the Music Industry

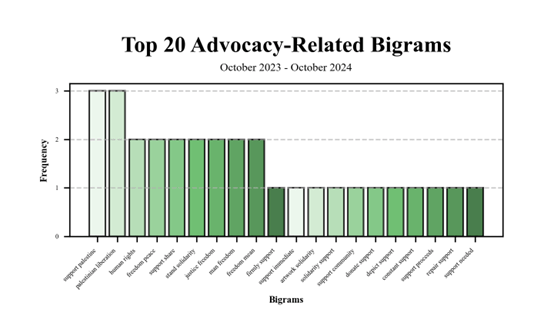

Figure 3: Record Label Location Frequency Map (Arshid, 2024)

Interactive map link: https://hanairs91.github.io/Bandcamp-Gaza-Fundraisers—Distant-Reading-and-Visualisation/

The algorithmically generated map (Figure 3) reveals a marked concentration of Bandcamp fundraisers by record labels based in Europe and North America, a phenomenon that resonates with a deep-rooted Western tradition of conceptualising humanitarianism as the political bedrock of global solidarity. The data also corroborates the view that humanitarian fundraising, as a political mechanism in response to crises, is significantly less prevalent in the Global South. Originally envisioned as a neutral, apolitical initiative with the establishment of the International Red Cross in the mid-19th century, humanitarianism has gradually morphed into a more politicised mode of global solidarity, particularly in the aftermath of World War II and the ascension of the liberal world order (Douzinas, 2007; Lawrence and Tavernor, 2019; Hopgood, 2019). This transformation, as noted by Lawrence and Tavernor (2019), gave rise to the notion of “mediated humanitarianism,” wherein media culture—spanning television, cinema, and music—became inextricably linked with humanitarian outreach and community formation, moulding and refracting efforts toward global solidarity from the mid-20th century onward. Chouliaraki (2010) further contends that contemporary media has catalysed the emergence of “post-humanitarianism,” which encourages politically ambivalent engagement and reduces humanitarian action to commodified, superficial acts of “playful consumerism.” The politicisation and mediation of humanitarianism have transformed it into what Douzinas (2007: 12) calls the “ultimate political ideology,” wherein Western well-being is intertwined with the hardships of the Global South.

Additionally, the dominance of Western record labels in Bandcamp fundraising efforts offers context for the tendency to prioritise universalist human rights discourse, with “Palestinian liberation” standing out as an exceptional case of a context-bound, relativist approach in the advocacy-related language (see Figure 2). The link between humanitarianism and universal human rights, two distinct manifestations of social activism (Hopgood, 2019), is deeply entrenched in Western tradition. Spivak (2023) and Douzinas (2007) maintain that NGO and relief efforts frequently serve to propagate Western neoliberal democracy under the guise of “human rights,” shaping social movements to conform to capitalist interests. While ostensibly framed as acts of solidarity, Western involvement in global crises can perpetuate imperialist sentiments and reinforce the dichotomy between the “rescuers” (those in the West) and the “suffering populations” (those in the Global South). Spivak’s (2023) radical rejection of philanthropic “giving” as a normative practice stems from her understanding that such gestures often obscure the complex historical and political realities of the situations they aim to address. Universal human rights, framed as a moral obligation, can undermine the agency of subaltern populations and place Western intervention at the centre (Spivak’s 2023; Douzinas, 2007). While Bandcamp fundraisers are organised by independent artists and labels, rather than large relief institutions, they still replicate some of the tropes of hegemonic structures from which they declare independence.

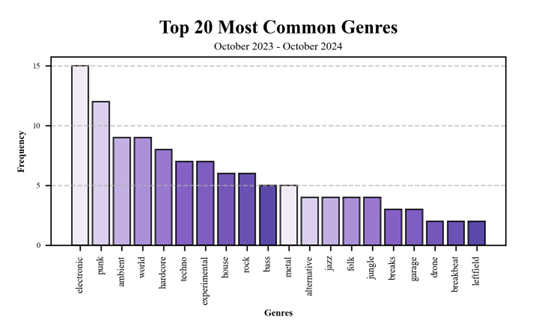

Distant reading of the tags labelling the albums and compilations sold to raise funds for Gaza shows that the highly contested category of “world music” ranks among the top four genres, following punk, a genre often associated with political protest and disobedience. Connell and Gibson (2004: 346) describe world music as a commercial construct that emerged in 1987 as a marketing strategy rather than an authentic genre tied to specific places. Historically, it served as a vague label for non-European and marginalised music, creating a division from other genres (Van Klyton, 2012). This divide enables Western corporations to profit by exoticising non-Western sounds and packaging them for global consumption (Connell and Gibson, 2004; Van Klyton, 2012). At its core, world music reflects the impact of globalised markets, where cultural products are detached from their geographic origins and recontextualised for Western audiences, which reinforces a Eurocentric framing of diverse cultural expressions and identities.

Figure 4: Top 20 Most Common Genres (Arshid, 2024)

Representation and the Commodification of Suffering

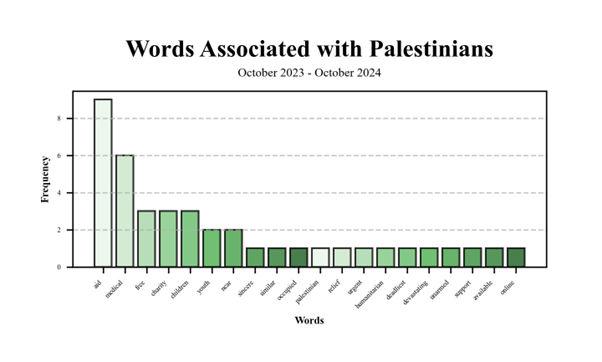

The distant reading results regarding words associated with Palestinians expose the power imbalances embedded in the narrative about the suffering of Global South populations (Ziberi et al., 2024) and humanitarian advocacy within the independent music community on Bandcamp. The most frequent terms linked to Palestinians predominantly revolve around the need for external help, casting Palestinians as passive beneficiaries of aid. The prominence of “charity” among the top four terms highlights that a segment of the fundraisers corresponds with Tullock’s (1971) definition of charity: where the affluent leverage their position to offer gifts to the less fortunate, with the quantity and nature of aid left at the benefactor’s discretion, as Buchanan (1987) suggests. Ethical theory distinctly separates charity from justice. While charity excludes the recipients from the process of planning systemic change, justice guarantees an entitlement to aid, rather than leaving it to the benevolence of others (Coss, 2019; Fang, 2021).

The above finding is further substantiated by an emphasis on vulnerable groups. The prevalence of terms like “children” and “youth” as demographic categories indicates that younger populations are significant in the discourse surrounding Palestinians. Such emphasis is further spurred by the facts outlined by international human rights organisations, such as Save the Children (2024), which ranked the occupied Palestinian territory as the most dangerous place in the world for children as of 10 October, 2024. However, this focus also resonates with the portrayal of children as inherently vulnerable in Western narratives, as Sergi (2021) argues, and is therefore designed to elicit maximum empathy for the Palestinian cause.

Figures 2 and 5 illustrate how immediacy and urgency are deployed as persuasion techniques within the fundraisers’ discourse. It is undeniable that swift action is urgently required in response to the crisis in Gaza. From a discourse perspective, however, urgency rhetoric also functions as an “attention economy” mechanism (Ziberi et al., 2024), a key principle in commodity theory, particularly relevant in the age of digital platforms. In this context, human attention is treated as a scarce and highly valuable resource in an oversaturated informational landscape. To facilitate the transactional process, i.e.,”buy this album, contribute to relief efforts in Gaza,” urgency transforms passive viewers into active contributors on the digital platform. Nayar (2009) explains that transforming struggles into a consumable public domain is a form of commodification that not only stirs empathy but is also intertwined with global media industries that profit from such representations (Nayar, 2009: 151-153). This raises important discussions around the ethics of representation and the asymmetries that are entrenched within them.

Figure 5: Words Associated with Palestinians (Arshid, 2024)

Supporter Engagement

Bandcamp’s resistance to platformised aesthetics, with its focus on materiality, permanence, and insularity (Hesmondhalgh et al., 2019), comes with practical limitations regarding the data available about supporters who purchase releases. Bandcamp uses a basic application programming interface (API) that offers simple functionalities for accessing and managing data. While it provides some metrics similar to those on social media platforms, the quantity of music purchasers is not displayed numerically. Instead, users are shown a collection of supporter avatars and comments. This basic API is intentional, contributing to the creation of “symbolic meaning” (Davies and Sigthorsson, 2013) around the music artefacts and their detachment from capitalist modes of production and circulation. However, it restricts insight into supporter behaviour to the analysis of comments on the record labels’ pages.

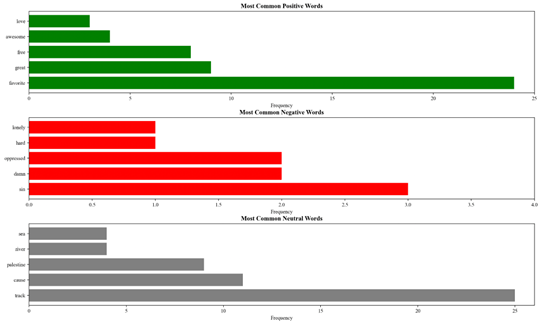

Reactions rooted in anger, fear, outrage, and sadness are typical crisis response stimuli (Ziberi et al., 2024), but sentiment analysis of Bandcamp fundraiser supporters’ comments reveals that positive sentiments dominate. Positive words appear 8 times more frequently than negative ones, with 4.5 times more overall occurrences, indicating a clear bias towards positive emotions despite some strong negative sentiment (see Figure 6). The word “favourite” is the most frequent, as many comments reference supporters’ favourite tracks from the albums. This demonstrates a pronounced interest in the record label’s music and reflects a transactional approach, with an emphasis on personal choice. Chouliaraki (2010) suggests that post-humanitarian communication has shifted towards individualised engagement, in which personal choice and spectator “reflexivity” assume a central role. Contemporary campaigns “technologise action” by reducing participation to quick, simplified clicks—such as online donations—that favour convenience over long-term moral and emotional commitment (Boltanski, 1999; Chouliaraki, 2010). This model of humanitarianism increasingly follows a consumption-based logic, where global solidarity is reduced to transactional gestures that give the impression of action while alleviating guilt (Hopgood, 2019).

Figure 6: Sentiment Analysis of Bandcamp Fundraiser Supporters’ Comments (Arshid, 2024)

Negative sentiment words contain strong language that is tinged with the gravity of the underlying geopolitical crisis and reflective of anger, hardship, and oppression. Pity-related terminology is conspicuously absent from the comments, which reflects a trend in contemporary humanitarian discourse to move away from the notion of a “crisis of pity,” where humanitarian appeals relying on grand emotions like guilt have lost their potency in galvanising sustained public action (Boltanski, 1999). As Douzinas (2007) and Müller (2013) note, pity is often a paternalistic emotion directed by the West towards the Global South to legitimise existing inequalities. While platform-based music fundraisers differ from the pity-driven humanitarianism that tainted antecedents such as Band Aid, they still operate within a marketised humanitarianism, marked by low emotional intensity and short-term engagement.

Concluding Thoughts

The distant reading of Bandcamp fundraisers for Gaza uncovers the complex power dynamics within digital humanitarianism, particularly in the independent music sector. Although the platform facilitates grassroots relief and advocacy initiatives, much of the engagement is transactional, centred on immediate relief efforts rather than addressing deeper structural issues. The prominence of consumer-driven activism, where music purchases are framed as acts of humanitarian support, exemplifies the commodification of suffering. This underscores longstanding patterns in Western humanitarianism, which often portray Palestinians as passive recipients of aid rather than active participants in their own liberation.

Further highlighting the dominance of Western narratives in sculpting humanitarian discourse is the geographic concentration of fundraisers in the Global North. The emphasis on vulnerable groups, especially children, evokes empathy, yet reinforces familiar tropes of victimhood. Urgency is frequently deployed as a persuasive device, reflecting the “attention economy” where immediate action is prioritised over sustained, critical engagement.

Sentiment analysis of supporter comments indicates a predominance of positive emotional responses, with relatively minimal engagement in negative or critical discourse. This suggests that supporters are primarily motivated by personal connection to the music or to the idea of contributing to a cause, rather than by the deeper political complexities of the Gaza crisis. While this reflects a shift away from pity-driven humanitarianism in the music industry, it also points to the limits of Bandcamp fundraisers as means for advocating long-term engagement with issues of structural inequality and injustice.

This study emphasises the imperative for further exploration of the visual and sonic rhetoric utilised in music industry fundraisers associated with the Gaza crisis. Such research has the potential to yield a more nuanced understanding of the independent music industry’s contributions to digital humanitarianism and activism.

Reference list:

- Allen, L.K., Creer, S.D. and Poulos, M.C. (2021) ‘Natural language processing as a technique for conducting text-based research’, Language and Linguistics Compass, e12433. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12433

- Appadurai, A., 2012. Commodities and the politics of value. In Interpreting objects and collections. Routledge, pp.76-91.

- Boehnert, J., 2016. Data visualisation does political things. DRS2016: Design+ research+ society: Future-focused thinking.

- Boltanski, L., 1999. Distant Suffering: Morality, Media and Politics. Translated by G. Burchell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Buchanan, A., 1987. Justice and charity. Ethics, 97(3), pp.558-575.

- Chouliaraki, L., 2010. Post-humanitarianism: Humanitarian communication beyond a politics of pity. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 13(2), pp.107-126. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877909356720>.

- Connell, J. and Gibson, C., 2004. World music: Deterritorializing place and identity. Progress in Human Geography, 28(3), pp.342-361.

- Coss, S., 2019. Confronting the NGO: Struggling for Agency and Approximating Freedom through the Works of Michel Foucault and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Pitzer Senior Theses. Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/102 [Accessed 2 October 2024].

- Davies, R. and Sigthorsson, G., 2013. Introducing the Creative Industries. SAGE, pp.1-21.

- Douzinas, C., 2007. The many faces of humanitarianism. Parrhesia, 2(1), pp.1-28.

- Fang, V., 2021. From charity to justice: how NGOs can revolutionise our response to extreme poverty. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

- George, J.J. and Leidner, D.E., 2019. From clicktivism to hacktivism: Understanding digital activism. Information and Organization, 29(3), p.100249. Available at: <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471772717303470?ref=pdf_download&fr=RR-2&rr=8cdd85096d62b78b> [Accessed 4 October 2024].

- Herman, E. and Chomsky, N., 1988. Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon.

- Hesmondhalgh, D., Jones, E. and Rauh, A., 2019. SoundCloud and Bandcamp as alternative music platforms. Social Media+ Society, 5(4), p.2056305119883429. Available at: <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2056305119883429> [Accessed 4 October 2024].

- Hopgood, S., 2019. When the music stops: Humanitarianism in a post-liberal world order. Journal of Humanitarian Affairs, 1(1), pp.4-14.

- Jones, A., 2017. Band Aid revisited: Humanitarianism, consumption and philanthropy in the 1980s. Contemporary British History, 31(2), pp.189-209.

- Kibble, R., 2013. Introduction to natural language processing. University of London. Available at: www.londoninternational.ac.uk [Accessed 2 October 2024].

- Lawrence, M. and Tavernor, R., 2019. Introduction: Global humanitarianism and media culture. In Global Humanitarianism and Media Culture, pp.1-12.

- Milbrath, L.W., 1981. Political participation. In The Handbook of Political Behavior: Volume 4. Boston, MA: Springer US, pp.197-240.

- Müller, T.R., 2013. The long shadow of Band Aid humanitarianism: Revisiting the dynamics between famine and celebrity. Third World Quarterly, 34(3), pp.470-484. <https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.785342>.

- Nayar, P.K., 2009. Scar cultures: Media, spectacle, suffering. Journal of Creative Communications, 4(3), pp.147-162.

- Neilson, L.A. and Paxton, P., 2010. Social capital and political consumerism: A multilevel analysis. Social Problems, 57(1), pp.5-24.

- Obad, O., 2011. Framing a friendly dictator: US newsmagazine coverage of Pakistani President Musharraf. Journal of Communication, 9 (11), p.2.

- Rogès, N., 2024. What is Bandcamp and is it the best solution to support artists? Available at: <https://soundiiz.com/blog/what-is-bandcamp-and-is-it-the-best-solution-to-support-artists/#:~:text=Fighting%20against%20giants,marketing%20focus%20than%20indirect%20competitors> [Accessed 4 October 2024].

- Save the Children, 2024. Gaza: At Least 3,100 Children Aged Under Five Killed with Others at Risk as Famine Looms. Available at: https://www.savethechildren.net/news/gaza-least-3100-children-aged-under-five-killed-others-risk-famine-looms [Accessed 4 October 2024].

- Sergi, D., 2021. Museums, refugees and communities, 1st edition. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429053474

- Sharma, D., 2017. Doing good, feeling bad: Humanitarian emotion in crisis. Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, 9(1). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/20004214.2017.1370357>.

- Snow, D.A., 2001. Collective identity and expressive forms. In: N.J. Smelser and P.B. Baltes, eds. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, Oxford: Pergamon Press, pp.2212-2219. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/04094-8>.

- Spivak, G.C., 2023. Death of a Discipline. Columbia University Press.

- Suárez, D.F., 2012. Grant making as advocacy: The emergence of social justice philanthropy. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 22(3), pp.259-280.

- Tullock, G., 1971. The charity of the uncharitable. Economic Inquiry, 9(4), p.379.

- Van Klyton, A., 2012. The social life of music: Commodification, space, and identity in world music production. Doctoral dissertation. King’s College London (University of London). Available at: <https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/31009547/2012_vanKlyton_Aaron_0731887_ethesis.pdf> [Accessed 4 October 2024].

- Ward, J. and de Vreese, C., 2011. Political consumerism, young citizens and the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 33(3), pp.399-413. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443710394900> [Accessed 4 October 2024].

- Ziberi, L., Lengel, L., Limani, A. and Newsom, V.A., 2024. Affect, credibility, and solidarity: Strategic narratives of NGOs’ relief and advocacy efforts for Gaza. Online Media and Global Communication, 3(1), pp.27-54. Available at: <https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/omgc-2024-0004/html#j_omgc-2024-0004_ref_002> [Accessed 4 October 2024].

Appendices

Appendix 1: Bandcamp Fundraisers Textual Data

Appendix 2: Python Code Developed for Data Analysis and Visualisation

- Top 20 Relief and Advocacy-Related Bigrams: https://github.com/HanaIrs91/Bandcamp-Gaza-Fundraisers—Distant-Reading-and-Visualisation/blob/main/relief%20and%20advocacy%20bigrams.py

- Record Label Location Frequency Map: https://github.com/HanaIrs91/Bandcamp-Gaza-Fundraisers—Distant-Reading-and-Visualisation/blob/main/folium%20map.py

- Top 20 Most Common Genres: https://github.com/HanaIrs91/Bandcamp-Gaza-Fundraisers—Distant-Reading-and-Visualisation/blob/main/genre%20updated.py

- Sentiment Analysis of Bandcamp Fundraiser Supporters’ Comments: https://github.com/HanaIrs91/Bandcamp-Gaza-Fundraisers—Distant-Reading-and-Visualisation/blob/main/Sentiment%20analysis%20-%20Final.py

- Words Associated with Palestinians: https://github.com/HanaIrs91/Bandcamp-Gaza-Fundraisers—Distant-Reading-and-Visualisation/blob/main/words%20associated%20with%20Palestinians.py

Appendix 3: Github Repository of the Research Project

https://github.com/HanaIrs91/Bandcamp-Gaza-Fundraisers—Distant-Reading-and-Visualisation