By Eva Schellingerhout, student in Arts and Culture Studies

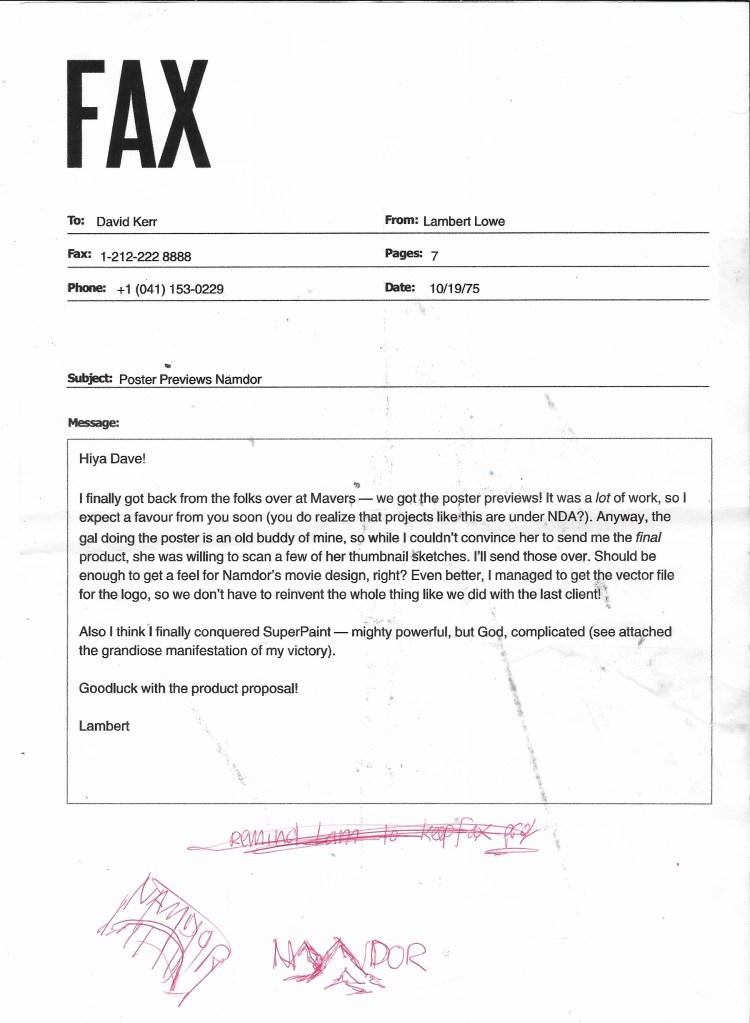

I got introduced to the cut-throat world of copyright and intellectual property at the tender age of eleven, watching a mini-documentary series with my father, called The Toys That Made Us. The series, in its attempt to follow the genealogy of famous childhood toys, exposed the bureaucratic slap-fight that occurred in the 70s and 80s over the merchandising rights to the latest Star Wars or He-Man. Corporate espionage, stolen trademarks, leaked product designs — it was a wild, dangerous world that endlessly intrigued me. This interest resurfaced when I was tasked with making my own transmedia story — I was going to create my own slap-fight, a company that would have competed with the likes of Kenner and Mattel at the heights of this ‘Toy War’. In the end, it became less a company, and more of a living, breathing person: David Kerr, a fictional toy product developer in the 70s, is contracted by a franchise to create a toy line, to accompany their upcoming film and collects his mementos of the work project in an archive box, where they sit, forgotten, for decades. The objects in the box are myriad: through advertisement blurbs, communication between the product designer and the client company, editor notes and sketches, the failings of a bled-dry franchise can be pieced together, alongside details about David’s personal life.

The archive brings two different branches of intermedial storytelling together: the ‘classical’ model of intermediality, Jenkin’s spatial transmedia “commercial franchise” and David Kerr’s personal life, which interacts with thing theory, archives and personal memory (Ryan 4).

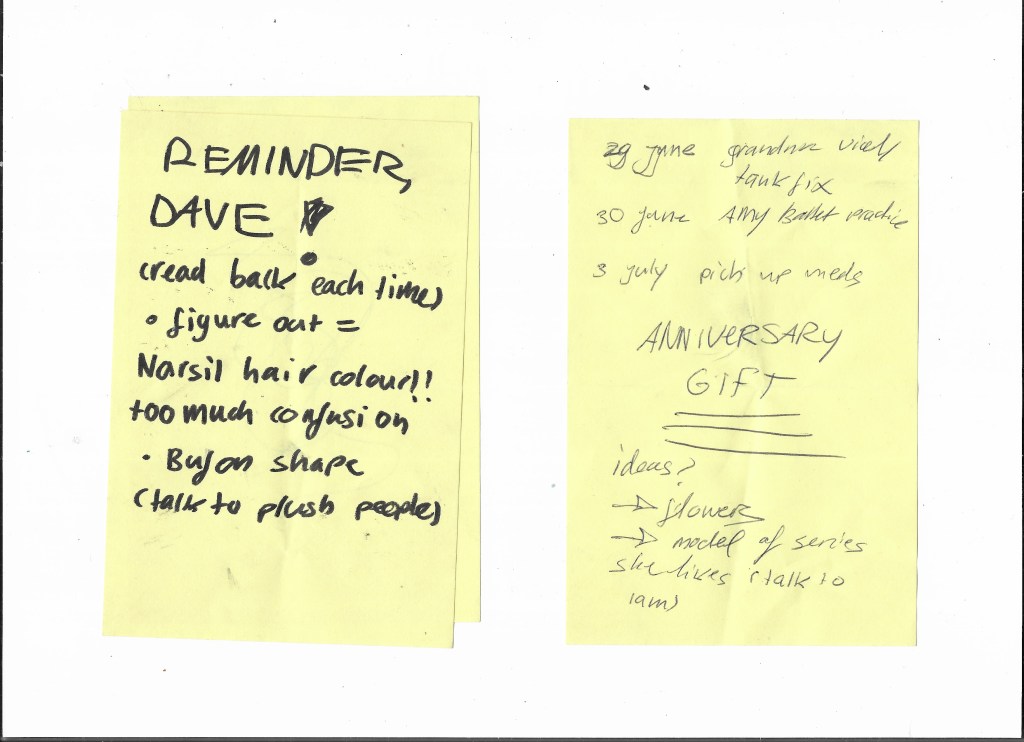

Following Heersmink’s model, my archive functions as an ‘autopography’, a “network of evocative objects” which “provides stability and continuity for … autobiographical memory and narrative self” and through interacting with these objects “we construct … our personal identity” or the “narrative self” (1846; 1830). I.e. by interacting with the evocative objects in the storage box, we construct a narrative for the product developer. During the process, the viewer endows objects with autobiographical meaning, imagining the relation between human actor and object. To promote this ‘endowing’ I aged the objects, scrunched up and tore the complaint letter and left out specific information. On a larger scale, how the ‘viewer’ chooses to construct the narratives they find in the box, whether this is the first or second branch or a combination of both, can be seen as cryptographic narratives being at play. The cryptographic narrative was conceptualised for video games that obscure a secondary, parallel story in their text not necessary for game completion, which can only be accessed through dedicated effort (Paklons and Tratseart 168). Because my project is also interactive and deals with constructing narratives out of “disparate plot points”, in a co-creation process between author and viewer, but also never confirms whether the constructed narrative is ‘correct’, the cryptographic narrative is a useful framework (Paklons and Tratseart 170).

Superficially, the storage box forms two branches of theory, or rather, invites two different modes of interaction, as I suggested earlier: the viewer can either connect with the commercial franchise, in the form of adverts and film posters, or with David Kerr, via grocery lists and sticky notes. In practice, this is a crude simplification of the inner workings of the box. Naturally, I cannot dictate which ‘story’ the viewer will find interesting. In essence, all objects can become a part of an infinite number of theoretical cryptographic narratives, at the whims of the viewer, since there exists no hierarchy, or even true division, between plot elements. The theory, therefore, that I outlined above, can be applied to all objects: the two branches exist simultaneously, it all depends on how the viewer interacts with the objects. Does the viewer acknowledge the constructed nature of the archive box and therefore treat the ‘personal memories’ of the product developer as clues instead of real memories, taking a cryptographic approach? Does the viewer see the representations of the commercial franchise as an extension of the narrative self of the product designer? And so on and so forth.

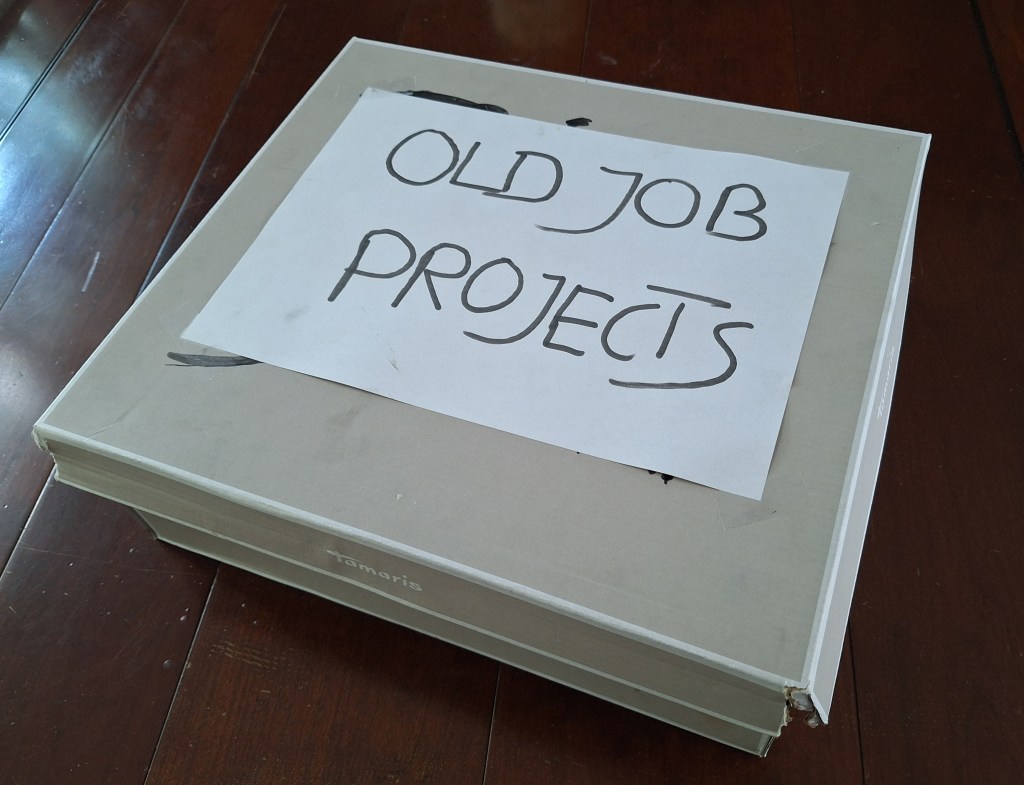

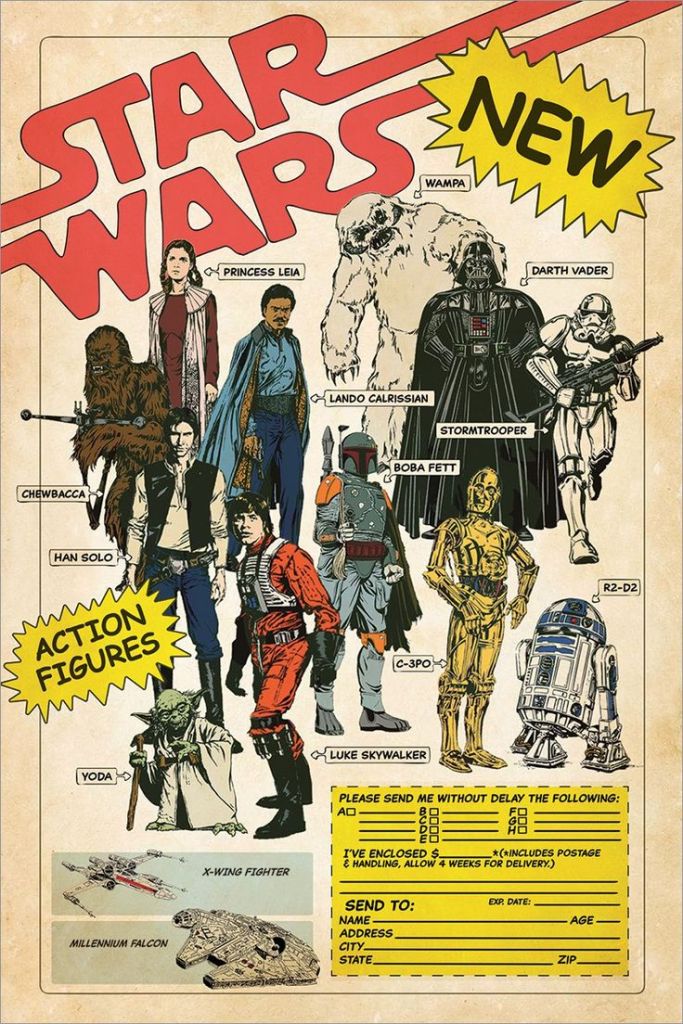

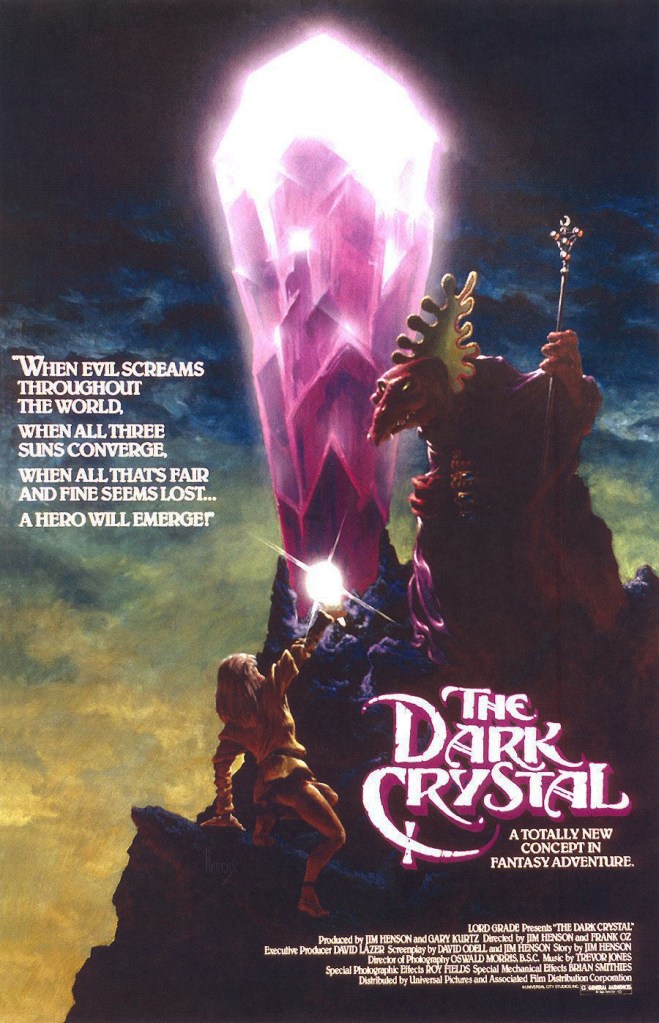

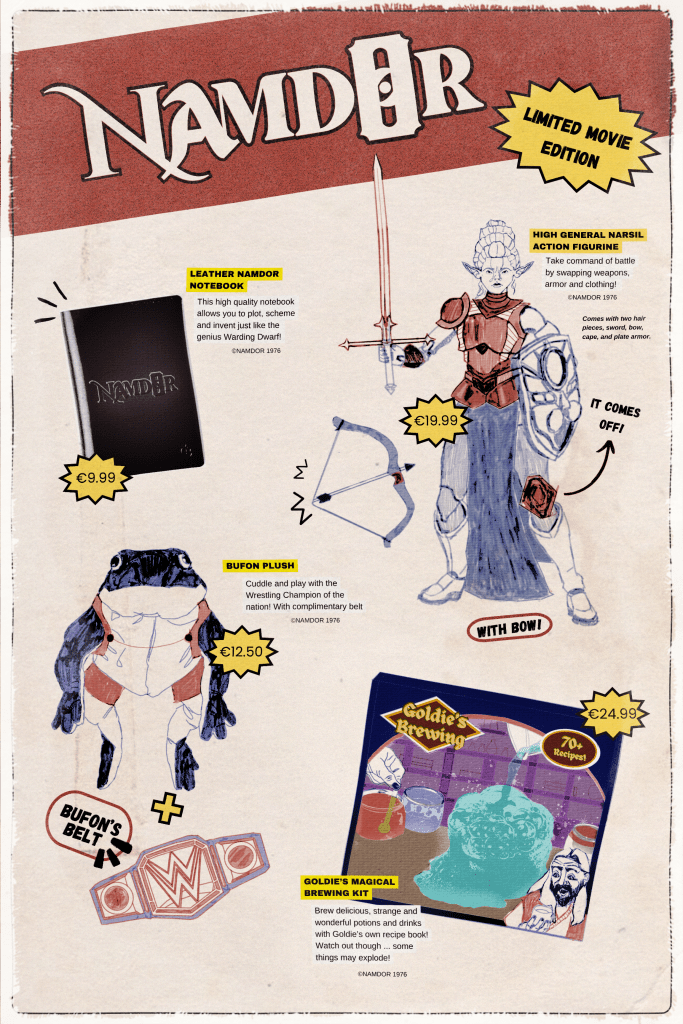

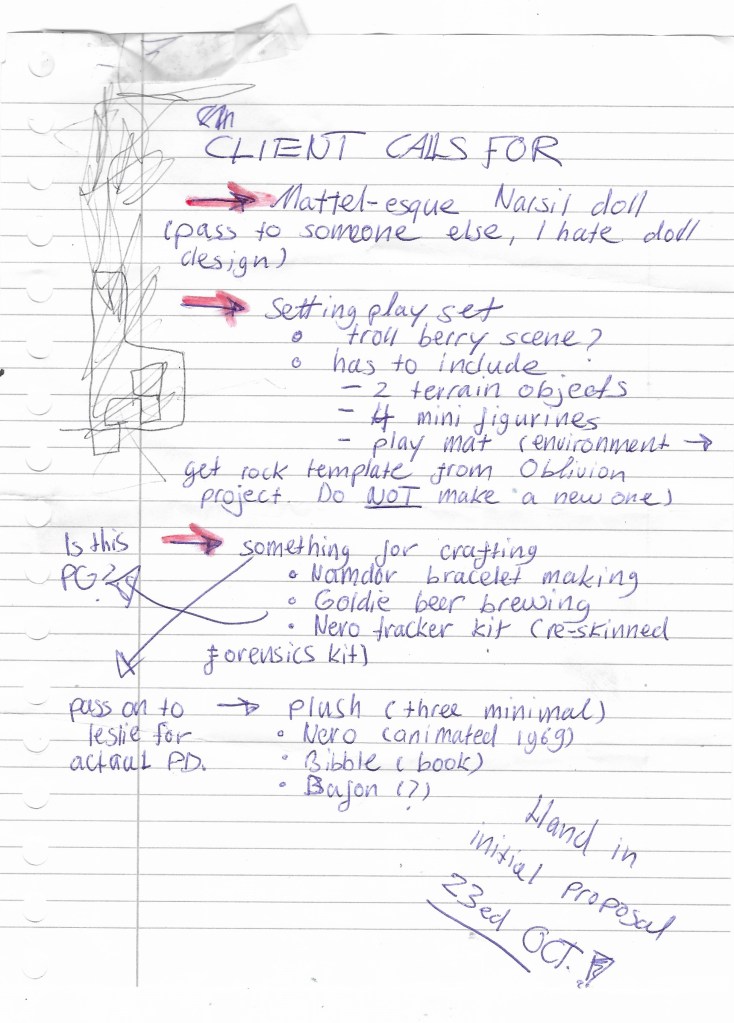

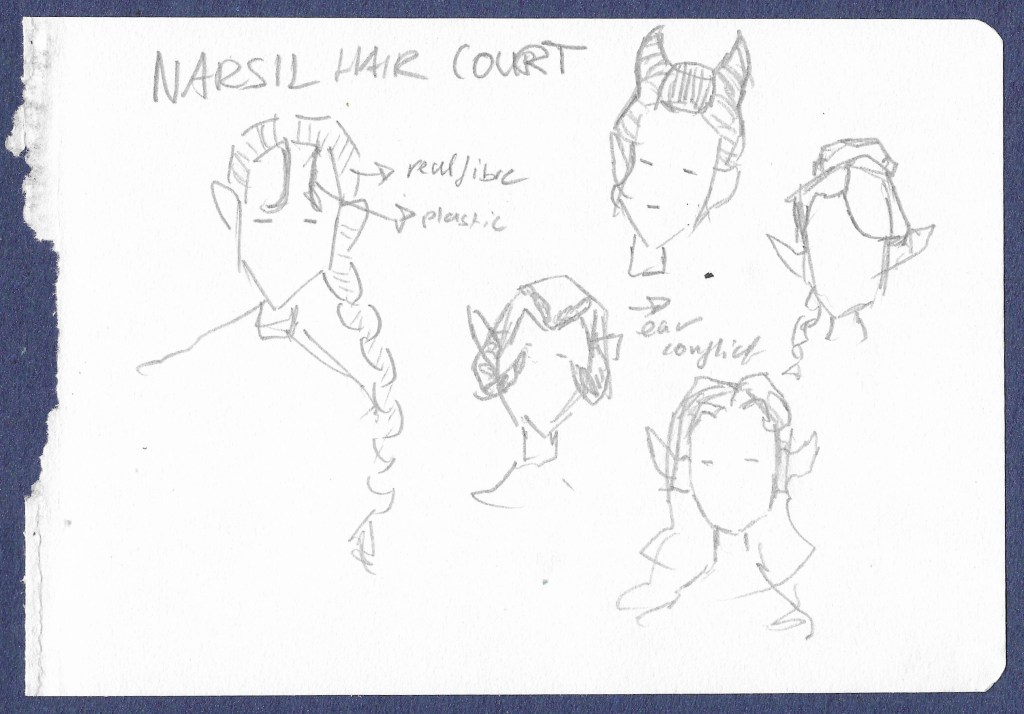

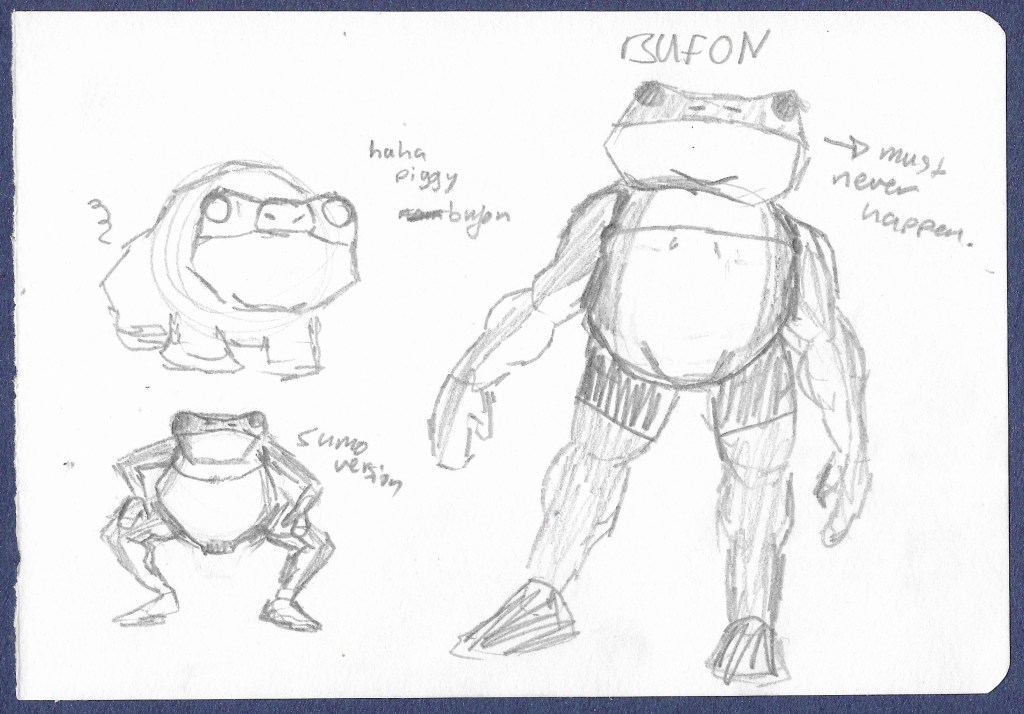

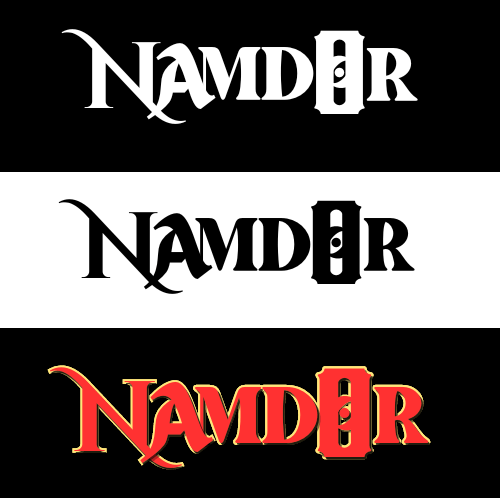

For the actual contents of the box, I compared archival documents, like old Star Wars, Transformers, Marvel, He-Man and Mattel adverts, and how they constructed their brand identity across multiple media (see the first image below this paragraph). For the poster, I drew from 80s fantasy films, like The Dark Crystal, The Labyrinth and The NeverEnding Story (see images 2 and 3). Once I started researching 70s and 80s idiosyncrasies, it became near compulsory to check each detail. It began with googling 1980s travel brochures — at this point my itinerary was much more ambitious — and ended with frantically searching for the computer standard typeface for word processors in the 1970s. It’s Helvetica, for those curious (image 4). All of this was endlessly fascinating to me, but I’ll stop myself, before I start waxing poetry about film poster composition, gauche colouring and standard 70s printing practices. Essentially, the viewer should be able to deduce a vague time estimate based on typography, colour, texture, ‘style’, and composition (image 5).

The biggest problem was verisimilitude — breaking the contract, stepping past David Kerr and inserting emphasis where none would have existed, proclaiming “Yes! This is what you should be looking at!”. An over-reliance on the cryptographic elements would train the viewer to only engage with the objects as potential clues, which would limit their engagement to a very narrow range of emotional investment (images below this paragraph).

The toys, especially, formed a roadblock. I was not just trying to create appealing designs — they would have to fit 70s sensibilities, while also reflecting the restraints David Kerr would have battled with, like time, budget and investor desires (images below this paragraph). When I went back to theory, I was able to put my worries to rest. Wolf writes, “Adaptation into a physical playset [or toy] … involves not so much the adaptation of a narrative, but rather the settings, objects, vehicles, and characters from which a narrative can be interactively recreated by the user” (169). Flattening these characters was integral to making a toy, I realized, which is a great narrative tool for my project at large.

Then, it was just a matter of shackling myself to my desk until my eyes went red and David Kerr had substantially come to life.

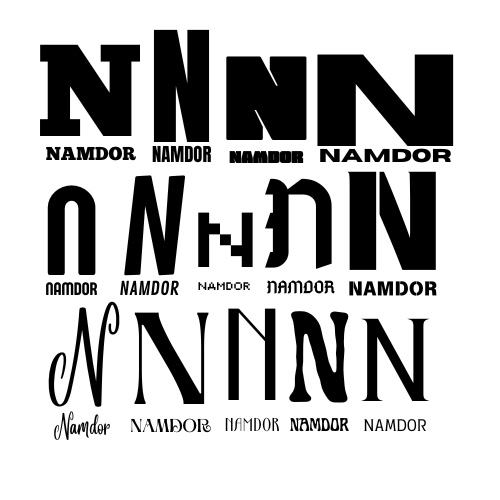

There is so much more I could mention about this project. How I arranged the objects in the box, how I re-folded and un-folded paper, the intricacies of all the scrapped product designs and rejected archive objects, how the Namdor logo is made from five typefaces and took an entire day (see image) — but alas.

The Namdor Archive box now rests behind my curtain, buried by a few sunhats, pillows and a children’s microscope. It has ironically, become a truer archive than it had ever previously been — the papers have bent beneath their own weight and some knickknacks from 2024 have found their final resting place inside. The box has already begun to fade from memory. I wait for someone to rediscover Me and David Kerr inside.

Works Cited

Heersmink, Richard. “The Narrative Self, Distributed Memory, and Evocative Objects.” Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition, vol. 175, no. 8, 2018, pp. 1829–49. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/45094122.

Hescox, Richard. “The Dark Crystal.” N.d., Pinterest, pin.it/5AYWXOEcU.

Paklons, Ana and An-Sofie Tratsaert. “The Cryptographic Narrative in Video Games: The Player as Detective.” Mediating Vulnerability: Comparative Approaches and Questions of Genre, edited by Anneleen Masschelein et al., UCL Press, 2021, pp. 168–84. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1nnwhjt.14.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. “Transmedia Storytelling: Industry Buzzword or New Narrative Experience?” Storyworlds: A Journal of Narrative Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2015, pp. 1–19. JSTOR, doi.org/10.5250/storyworlds.7.2.0001.

Star Warsaction figurine comic book advertisement. 1977-1978?, Star Wars, www.starwars.com/empire-40th.

Wolf, Mark J. P. “Adapting the Death Star into LEGO: The Case of LEGO Set #10188.” Star Wars and the History of Transmedia Storytelling, edited by Sean Guynes and Dan Hassler-Forest, Amsterdam UP, 2018, pp. 169–86. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt207g5dd.16.