By Edwin van Meerkerk

For the past year and a half I have had a series of intensive talks with lecturers and students all over campus. This is part of an educational innovation project on sustainability in education. Since I am specialized in – and fascinated by – teaching and learning, this project is also a way to dive more deeply into the question what we are talking about when we’re talking about education – or rather: what are we doing when we’re ‘doing education’? For this project, we visited every nook and cranny of our campus and met with staff and students from 38 bachelor’s programmes. And while our ‘sample’ of lecturers and students is not statistically representative, some patterns are starting to emerge that go beyond the specific group of people we talked to.

We started our first interview by asking students and lecturers to describe their programme in two or three sentences – as if they were at a family gathering and an aunt or uncle asks “what is it you’re studying again?” All save one of our 76 interviewees answered by describing the content of the curriculum: “my study is about …” That may seem logical, but it is highly problematic, given that in the subsequent interviews and workshops we organized, we found a consistent pattern of focus on the content (also referred to as “the basis” or “the core”) and a disturbing silence when it came to identifying what students are able to do with that content. Both lecturers and students found it very hard to tell which skills, attitudes, or competencies students learn. Digging deeper into this matter, we found that (luckily) students actually do learn important skills, but that in many cases these skills were not assessed or given feedback on. We call this the hidden curriculum.

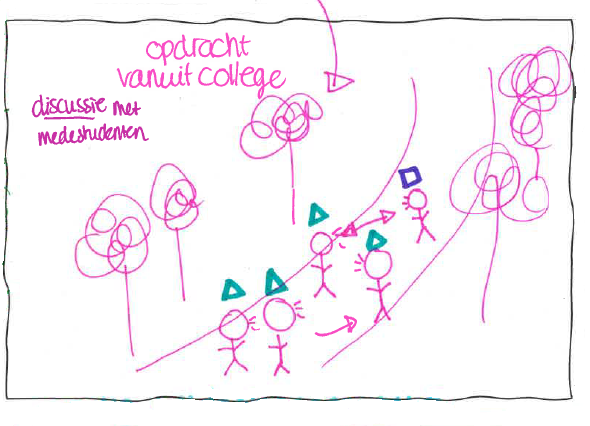

This hidden curriculum at universities is a curriculum that, in the words of one of the participant lecturers, was “who we really are”. Students across disciplines affirmed that they could recognise fellow students by these skills and attitudes as different from students in other disciplines. But how do students acquire these skills? As one lecturer put it, between classes “magic happens”, without the lecturers explicitly guiding or steering students in this learning process. We then tried to make this explicit by asking lecturers and students to make a storyboard of the learning process, visualising student activity during a course. This proved to be a difficult, but often revealing exercise. Reflecting on one’s learning process, developing critical thinking skills, learning to work in teams are key objectives, yet they very likely happen outside our lecture halls.

It is time that we recognise that the most important aspect of our discipline is not what it is about, but what we want our students to be able to do with the content we are treating in class. Only then can we answer why it is important for cultural students to be able to analyse films, songs, visual art, theatre, and poetry; why it is extremely relevant for students (and for society) that people are trained to critically analyse cultural practices and policy. Because we are just as relevant as any other discipline, from Economy to Physics, from Computing Science to Psychology. The world needs public servants, journalists, educators, and other professionals who are able to critically reflect on the cultural aspect of the global crises we are in the middle of: climate, migration, housing, social safety, discrimination, and war. And we do teach them that – we just don’t always know how.

Do you want to think with us in opening up our hidden curriculum? Send me a message at edwin.vanmeerkerk@ru.nl.